Near Fort Hall in Bingham County, Idaho — The American West (Mountains)

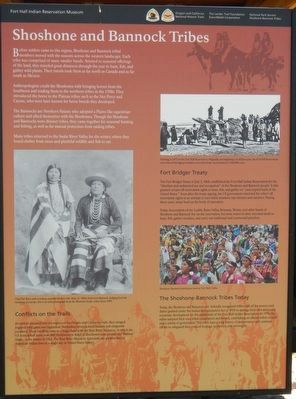

Shoshone and Bannock Tribes

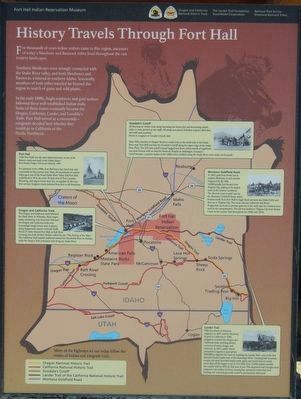

History Travels Through Fort Hall

Photographed By Barry Swackhamer, June 22, 2017

1. Shoshone and Bannock Tribes panel

Photo captions: (center left) Chief Pat Tyhee with a woman, possibly his first wife, Mary (b. 1864); both were Bannock. Judging from the backdrop and props, this is an early photograph from the Wrensted studio, taken about 1895.; (upper right) Farming in 1872 on the Fort Hall Reservation. Originally encompassing 1.8 million acres, the Fort Hall Reservation was reduced through government acts and private encroachment to 544,000 acres.; (lower right) Shoshone-Bannock festival pow wow in Fort Hall, Idaho.

Panel 1:

Before settlers came to this region, Shoshone and Bannock tribal members moved with the seasons across the western landscape. Each tribe was comprised of many smaller bands. Attuned to seasonal offerings of the land, they traveled great distances through the year to hunt, fish, and gather wild plants. Their travels took them as far north as Canada and as far south as Mexico.

Anthropologists credit the Shoshone with bringing horses from the Southwest and trading them to the northern tribes in the 1700s. They introduced the horse to the Plateau tribes such as the Nez Perce and Cayuse, who were later known for horse breeds they developed.

The Bannocks are Northern Paiutes who adopted a Plains-like equestrian culture and allied themselves with the Shoshone. Though the Shoshone and Bannocks were distinct tribes, they came together for seasonal hunting and fishing, as well as for mutual protection from raiding tribes.

Many tribes returned to the Snake River Valley for the winter, where they found shelter from snow and plentiful wildlife and fish to eat.

As settlers streamed into the region on the Oregon and California trails, they ravaged regional wild game and vegetation. Skirmishes between local Indians and emigrants escalated. These conflicts came to a tragic head with the Bear River Massacre, in which the US Army killed more than 400 Northwest Band of Shoshones near present day Preston, Idaho, in the winter of 1863. The Bear River Massacre represented the greatest loss of American Indian lives in a single day in United States history.

The Fort Bridger Treaty of July 3, 1868, established the Fort Hall Indian Reservation for the "absolute and undeterred use and occupation: of the Shoshone and Bannock people. It also granted certain off-reservation rights to hunt, fish, and gather on "unoccupied lands of the United States." Soon after the treaty signing, the US government restricted the tribes' off reservation rights in an attempt to turn tribal members into farmers and ranchers. During these years, many lived on the brink of starvation.

Today, descendants of the Lemhi, Boise Valley, Brunei, Weiser, and other bands of Shoshone and Bannock live on the reservation, but most return to their ancestral lands to hunt, fish, gather, socialize, and carry out traditional and ceremonial practices.

Photographed By Barry Swackhamer, June 22, 2017

2. History Travels Through Fort Hall panel

Legend: Many of the highways we use today follow the routes of Indian and emigrant trails.

(yellow) Oregon National Historic Trail

(red) California National Historic Trail

(brown) Goodale's Cutoff

(black) Lander Trail of the California National Historic Trail

(purple) Montana Goldfield Road

(yellow) Oregon National Historic Trail

(red) California National Historic Trail

(brown) Goodale's Cutoff

(black) Lander Trail of the California National Historic Trail

(purple) Montana Goldfield Road

Panel 2:

For thousands of years before settlers came to this region, ancestors of today's Shoshone and Bannock tribes lived throughout the vast western landscapes.

Northern Shoshones were strongly connected with the Snake River valley, and both Shoshones and Bannocks wintered in southern Idaho. Seasonally, members of both tribes traveled far beyond this region in search of game and wild plants.

In the early 1800s, Anglo explorers and gold seekers followed there well-established Indian trails. Some of these routes eventually became the Oregon, California, Lander, and Goodale's Trails. Fort Hall served as a crossroads - emigrants decided here whether they would go to California or the Pacific Northwest.

Fort Hall

"(Old Fort Hall) was the

most important point on any of the historic roads and trails in the United States." Ezra Meeker, Oregon Trail preservationist, 1906

For pioneers in the 1800s, Fort Hall was a key travel stop and crossroads on the journey west. Here, the mountains of eastern Idaho gave way to the broad Snake River Valley. Old Fort Hall, established in 1834, lay some 30 days west of Fort Laramie, Wyoming, and wagon teams were low on supplies by the time they arrived. Emigrant roads radiated from here in all directions.

Oregon and California Trails

The Oregon and California trails followed the Platte River in Nebraska. Most wagon trains continuing west from here followed the Oregon and California trails over increasingly rough terrain and, in places, along dangerously narrow river bluffs. About 25 miles beyond Fort Hall, at Raft River Crossing, the trail divided. Settlers called the site "The Parting of the Ways." The California Trail headed southwest toward the Humboldt River in Nevada, while the Oregon Trail continued west along the Snake River.

Goodale's Cutoff

All day long we slowly creep along lacerating our horses feet and threatening wheels, axles, or some portion of our outfit. All along were pieces of broken wagons which had met with accidents. Harriet A. Longhary on Goodale's Cutoff, 1864

After 1852, travelers to Oregon Territory could cross to the north side of the Snake River near Fort Hall and take the Goodale's Cutoff along the upper edge of the Snake River Plain. The 230-mile cutoff crossed rugged lava flows, dense stands of sagebrush, and sand barrens with no feed for livestock. Despite its challenges, Goodale's Cutoff became a popular option in the late 1860's when conflicts along the Snake River route made travel unsafe.

Montana Goldfield Road

In 1863, gold fever broke out in western Montana, in and around Virginia City. By 1864, 10,000 people had flooded into Virginia City, making it the largest town in the interior northwest. The shortest route to gold was via the Montana Goldfield Road, which headed north from Fort Hall to Eagle Rock (present-day Idaho Falls) and then on to Virginia City. This route was also called the Salt Road. Prospectors used salt to process gold ore in the early days by a method once used by conquistadors. The salt was hauled to Virginia City from Stump Creek on the Lander Trail throughout the 1860s and 1870s.

Lander Trail

With the advent of Mormon migration in 1847 and the discovery of gold in California in 1848, emigrants crowded the Oregon and California trails, straining limited resources of water, forage, and firewood. In 1857, public outcry prompted Congress to appropriate $300,000 to improve the route by building the Lander Trail - one of the first federally funded roads west of the Mississippi River. Crossing lush mountain terrain, the route provided ample water, grass and wood and cut nearly seven days off the wagon route to Fort Hall. Over 13,000 settlers traveled the Lander Trail in 1859, its first year of use. This improved road brought more emigrants into Indian territory, causing fear among the tribes that their hunting and wintering grounds would be permanently destroyed.

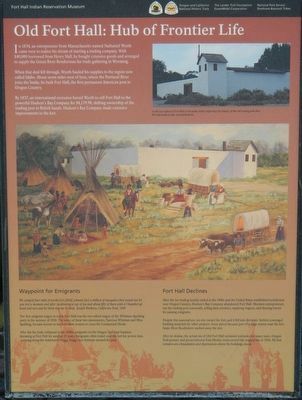

Panel 3:

8667 In 1834, an entrepreneur from Massachusetts named Nathaniel Wyeth came west to realize his dream of starting a trading company. With $40,000 borrowed from Henry Hall, he bought extensive goods and arranged to supply the Green River Rendezvous fur trade gathering in Wyoming.

When that deal fell through, Wyeth hauled his supplies to the region now called Idaho. About seven miles west of here, where the Portneuf River joins the Snake, he built Fort Hall, the first permanent American post in Oregon Country.

By 1837, an international recession forced Wyeth to sell Fort Hall to the powerful Hudson's Bay Company for $8,179.98, shifting ownership of the trading post to British hands. Hudson's Bay Company made extensive improvements to the fort.

We camped four miles from the fort (Hall) almonst (sic) a million of mosquitoes they would not let you rest a moment and after swallowing a cup of tea and about fifty of them with it I bundled up head and ears and let them sing me to sleep. Joseph Hackney, California Trail, 1849

The first emigrant wagon to reach Fort Hall was the two-wheel wagon of the Whitman-Spalding party in the summer of 1836. The wives of the two missionaries, Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding, became known as the first white women to cross the Continental Divide.

After the fur trade collapsed in the 1840s, emigrants on the Oregon Trail kept business booming at Fort Hall for another 15 years. Emigrants often rested near the fort for several days, camping along the notoriously buggy, boggy river bottoms around the post.

After the fur trading heyday ended in the 1840s and the United States established jurisdiction over Oregon Country, Hudson's Bay Company abandoned Fort Hall. Mormon entrepreneurs ran the trading post seasonally, selling farm produce, repairing wagons, and shoeing horses for passing emigrants.

Despite this seasonal use, no one owned the fort, and it fell into disrepair. Settlers scavenged building materials for other projects. Some pieces became part of a stage station near the fort. Snake River floodwaters washed away the rest.

After its demise, the actual site of Old Fort Hall remained unknown for many years. Oregon Trail pioneer and preservationist Ezra Meeker rediscovered the original site in 1916. All that remains are a foundation and depressions when buildings stood.

Erected by Shoshone-Bannock Tribes, National Park Service, and Oregon and California National Historic Trails.

Topics. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: Forts and Castles • Native Americans • Roads & Vehicles • Settlements & Settlers. A significant historical date for this entry is July 3, 1868.

Location. 43° 1.318′ N, 112° 24.663′ W. Marker is near Fort Hall, Idaho, in Bingham County. Marker is on Ross Fort (Simplot) Road near Interstate 15, on the left when traveling west. Touch for map. Marker is in this post office area: Fort Hall ID 83203, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within 13 miles of this marker, measured as the crow flies. Shoshone-Bannock Tribes: Beyond the Reservation (within shouting distance of this marker); Newe'm Bo'ai -- "Indian Road" (within shouting distance of this marker); Fort Hall (approx. 1.4 miles away); Shoshone-Bannock Tribes Memorial Honor Roll (approx. 1.4 miles away); Chief Theater (approx. 11.2 miles away); Utah & Northern Railroad (approx. 11.2 miles away); Idaho State University (approx. 11.3 miles away); Central Ferry Station (approx. 12.1 miles away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Fort Hall.

More about this marker. This marker is located at the Shoshone-Bannock Information Center near the Ross Fork (Simplot) Road exit (Exit 80) of Interstate 15.

Credits. This page was last revised on September 20, 2017. It was originally submitted on September 20, 2017, by Barry Swackhamer of Brentwood, California. This page has been viewed 542 times since then and 34 times this year. Photos: 1, 2, 3, 4. submitted on September 20, 2017, by Barry Swackhamer of Brentwood, California.