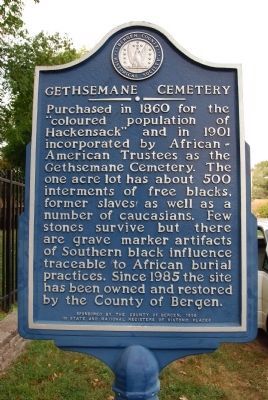

Gethsemane Cemetery

Sponsored by the County of Bergen 1998

In State and National Registers of Historic Places

Erected 1998 by County of Bergen.

Topics. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: African Americans • Cemeteries & Burial Sites • Government & Politics. A significant historical year for this entry is 1860.

Location. 40° 51.317′ N, 74° 2.467′ W. Marker is in Little Ferry, New Jersey, in Bergen County. Marker is on Summit Place, half a mile north of U.S. 46, on the right when traveling south. Touch for map. Marker is in this post office area: Little Ferry NJ 07643, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within 2 miles of this marker, measured as the crow flies. Paulison – Christie House (approx. ¾ mile away); Revolutionary War Cemetery (approx. 1.2 miles away); Teterboro Airport

Regarding Gethsemane Cemetery. Gethsemane Cemetery is located west of the Hackensack River in the northern half of Little Ferry, NJ. It’s not known when the first interment was made here. A deed of sale on November 17, 1860 to three prominent white Hackensack residents states that this one acre of land was to be used as a “cemetery for the colored population of the Village of Hackensack…” On March 21, 1901, the Gethsemane Cemetery Association was incorporated and the “Colored Cemetery” passed from white to black trusteeship. Seven trustees were appointed: William Hire, William Jackson, Thomas See, Thomas H. Tiebout, James P. Westcomb, George W. White, and Samuel Winfield. The cemetery’s official name then became Gethsemane Cemetery.

The cemetery is located on a 1-acre sandy hill bordered on the west by Liberty (Moonachie) Road, which dates from 1819, and on the east Summit Place. Further to the east is the Bergen Turnpike road, originally laid out in 1804. Historically this area has been called “Sand Hill,” and the burial ground was sometimes called San or Sand Hill Cemetery.

The graves of over 500 people have been documented here. They include that of Elizabeth Dulfer who was born a slave c1790, freed in 1822, and died in 1880. During the 19th century, the clay pits in this area became the source of thriving brick and pottery industries. Among those who had the foresight to tap into these deposits was Elizabeth. She began amassing land here early in 1847 and eventually became one of the areas wealthiest businesswomen and landholders.

Two Civil War veterans, Peter M. Billings and Silas M. Carpenter, were also buried here but they have no grave markers. Both served in the Union Army in the Twenty-Ninth (Colored) Connecticut Volunteer Regiment, an Infantry unit that was ultimately one of the four “colored” regiments in the Tenth Corps. Carpenter was born in Connecticut and Billings in New Jersey.

Fewer than fifty gravestones, some only fragments, still exist. Twenty-seven stones have inscriptions; the carved dates of death range between 1878 and 1911. Low stone and metal fences outlined a few family plots.

It is notable that African-American tradition places great importance on burial. It should be remembered that the presence or lack of gravestones at Gethsemane do not necessarily reflect the economic or social status of the deceased or their families. Of great significance are the terra-cotta pipe grave-markers that were found here in the 1980s. These are evidence of surviving West African burial customs that have been found in southern cemeteries. These clay pipes, in addition to connecting the world of the living and the dead, were water-related, an example of African symbolism.

Gethsemane Cemetery figured prominently in the controversy surrounding the burial of Samuel Bass, sexton of Hackensack’s First Baptist Church. It was reported in The Hackensack Republican of January 31, 1884, that when he died that month he was denied burial in the all-white Hackensack Cemetery. Instead, his family and church had to bury him in Gethsemane Cemetery. Public feeling was heated and reached beyond the local area. Besides the local Bergen County Democrat and The Hackensack Republican newspapers, several articles on this denial of burial appeared in The New York Times and The New York Globe.

This situation was brought before the New Jersey state legislature by the state’s newly-elected governor, Leon Abbett. He protested the denial and in a strong statement to the State Legislature said:

“The regulation that refuses a Christian burial to the body of a deceased citizen upon the ground of color is not, in my judgment, a reasonable regulation, and therefore the church has the right to make the interment...The Legislature should see that the civil and political rights of all men, whether white or black are protected...It ought not be tolerated in this State that a corporation whose existence depends on the Legislature's will, and whose property is exempt from taxation because of its religious uses, should be permitted to make a distinction between a white man and a black man.”

Two months later in March 1884, legislation dubbed the “Negro Burial Bill” was passed.

Burials continued in Gethsemane until the 1920s. Over time the site was neglected and vandalized. Stones were stolen or broken, and the cemetery became a dumping ground for car parts, garbage and all matter of items. When the cemetery’s very existence was threatened with destruction through development, members of the African-American community began the fight to save it. By 1985, title passed to Bergen County which saved it from the proposed development.

In the 1980s, now a Bergen County-owned historic site, archaeologist Dr. Joan Geismar performed and supervised in-depth research, analysis and restoration work at Gethsemane financed by the county. The staff of the Bergen County Division of Cultural and Historic Affairs (DCHA) and volunteers of the African-American Studies Committee of the Bergen County Historical Society conducted a comprehensive survey and inventory of the site. In 1988 gravestone conservationist Lynette Strangstad began repairing some of the stones. In 1989 Dr. Geismar and James Mellett conducted non-intrusive Ground Penetrating Radar surveys which determined the locations and approximate number of burials. In 1992 the DCHA published Dr. Geismar’s resulting research in the book: Gethsemane Cemetery in Death and Life.

Few written records have been found for burials dating from before the 1870s at Gethsemane. Most likely there were earlier burials but these remain unknown. The first documented burial was that of Cornelia Smith, a 10-month old infant known from her gravestone to have died August 13, 1866. Records from the local Ricardo Funeral Home, the establishment responsible for many Gethsemane burials beginning in 1885, provided much of the information on who was buried here. From its beginning, Gethsemane served as a family cemetery for the local African-American population; after 1884 it also became a potter’s filed for indigent Caucasians. The two most common family names found at Gethsemane are Thompson, with 21 documented burials, and Jackson, with 22. The last documented burial, that of Louis Swinney, occurred on December 14, 1924.

Although the location of Gethsemane’s original entrance is unknown, a plain sandstone obelisk that stands in what is believed to be its original position approximately half way between Liberty Street and Summit Place, may provide a clue. There are no burials associated with it and a corridor devoid of burials runs from the obelisk to the southern boundary. This suggests that the entrance was in this area.

In 1994 Gethsemane Cemetery was entered onto the New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places due to the significant role it played in the enactment of New Jersey’s early civil rights legislation as well as containing evidence of West African burial customs.

In 2003 the County celebrated the dedication of new meditation areas with interpretive panels that tell the story of this historic cemetery. They include three panels with the names of 515 of those buried here. Over 300 people attended the dedication and listened to music from the Hameed Drum & Dance Company, Garden State Choral Chapter and singer Sophia Saxon, and speeches by the N.J. Secretary of State Regena Thomas, County Executive Dennis McNerney, the late Giles Wright, Director of the New Jersey Historical Commission’s Afro-American Program, archaeologist Dr. Joan Geismar, poet Jeannette Curtis-Rideau and Gethsemane Historian Arnold Brown.

The Division of Cultural and Historic Affairs began Phase 1 tombstone restoration project in the spring of 2007. Stones were repaired and cleaned by cemetery restoration specialist and Robert Neal Carpenter.

After lying flat face-up in the ground for decades, the large Henry White tombstone was erected and placed on its base stone. Revealed for the first time in living memory were the names of five of Henry’s siblings carved on the reverse side: George, Leah Anna, Amos, Clarence and Willet.

Also repaired and erected was the stone for William Robinson, who served on the U.S.S. Savannah and died in 1889.

Phase 2 of tombstone restoration and cleaning was completed in 2008.

Additional keywords. Civil Rights, Sand Hill Cemetery, clay pipes, Civil War veterans.

Credits. This page was last revised on June 16, 2016. It was originally submitted on June 23, 2011, by Janet E. Strom of Hackensack, New Jersey. This page has been viewed 1,171 times since then and 24 times this year. Photos: 1, 2, 3, 4. submitted on June 23, 2011, by Janet E. Strom of Hackensack, New Jersey. • Bill Pfingsten was the editor who published this page.