Belle and Mayo Islands in Richmond, Virginia — The American South (Mid-Atlantic)

African Americans and the Waterfront

Richmond Riverfront

— Richmond Slave Trail —

The Richmond waterfront is steeped in African American history. From the early days when Richmond was a colonial trading post, free, indentures, and enslaved African Americans lived and worked in the area. Later, the Richmond dock became a place of arrival for many slaves brought from other parts of the South to be sold at auction houses a few blocks north of here.

Both free and enslaved blacks worked in the ironworks and tobacco warehouses along the waterfront, and on the river, canals, and docks. African American batteauxmen, who plied both the James River and the canals, were known for the skill and daring with which they navigated the river’s rocks and rapids.

(caption) African American batteauxman. From Harper’s Weekly, 1874. Valentine Museum

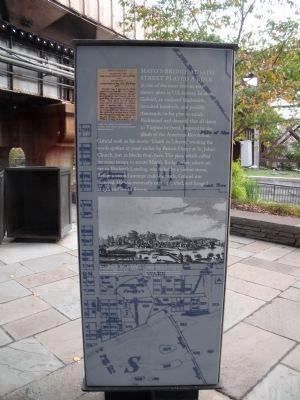

Mayo's Bridge

Mayo’s Bridge at 14th Street played a role in one of the most famous anti-slavery plots in U.S. history. In 1800, Gabriel, an enslaved blacksmith, recruited hundreds, and possibly thousands, to his plan to attack Richmond and demand that all slaves in Virginia be freed. Inspired by the ideals of the American Revolution, Gabriel took as his motto “Death or Liberty,” evoking the words spoken 25 years earlier by Patrick Henry at St. John’s Church, just 10 blocks from here. The plan, which called for some troops to secure Mayo’s Bridge, while others set fire to Rockett’s Landing, was foiled by a violent storm. Before a second attempt could be made, Gabriel was betrayed. He was eventually captured, tried, and hanged at 15th and Broad Streets.

(captions)

Excerpt of an article from the Richmond Recorder, 1803, concerning Gabriel’s Rebellion. Valentine Museum

Above, Richmond, 1817, showing Mayo’s Bridge spanning the James River. Image from Letters of a British Spy, by William Wirt, 1817. The Library of Virginia

Background, detail from “A Plan of the City of Richmond,” by Richard Young, c. 1809, showing Mayo’s Bridge, a strategic target of Gabriel's insurrection plot. Redrawn by the Department of Public Works, Bureau of Survey & Design, April 14, 1932. The Library of Virginia

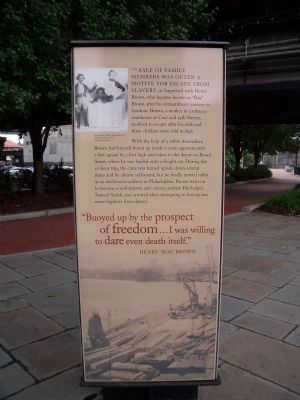

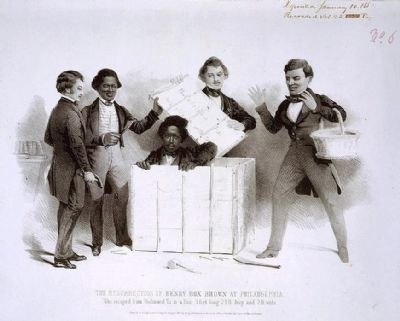

Henry "Box" Brown

The sale of family members was often a motive for escape from slavery, as happened with Henry Brown, who became known as “Box” Brown after his extraordinary journey to freedom. Brown, a worker in a tobacco warehouse at Cary and 14th Streets, resolved to escape after his wife and three children were sold in 1848.

With the help of a white shoemaker, Brown had himself boxed up inside a crate approximately 2 feet square by 3 feet high and taken to the depot on Broad Street, where he was loaded onto a freight car. During the 27-hour trip, the crate was turned upside down several times and he almost suffocated, but he finally arrived safely at an abolitionist address in Philadelphia. Brown went on to become a well-known anti-slavery activist. His helper, Samuel Smith, was arrested after attempting to box up two more fugitives from slavery.

“Buoyed up by the prospect of freedom…I was willing to dare even death itself.” Henry “Box” Brown

(caption) Above, Henry “Box” Brown upon his deliverance from slavery. Library of Congress

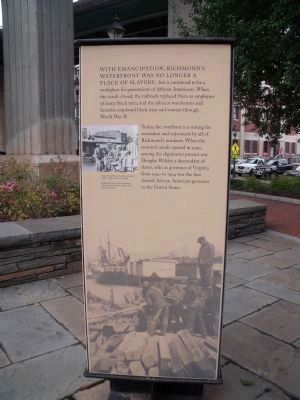

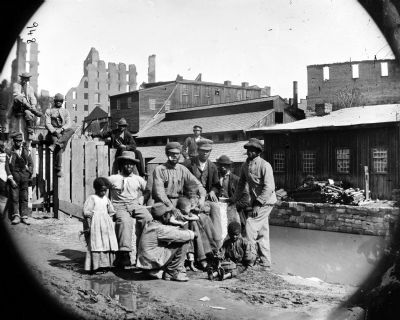

Emancipation

With emancipation, Richmond’s waterfront was no longer a place of slavery, but it continued to be a workplace for generations of African Americans. When the canals closed, the railroads replaced them as employers of many black men, and the tobacco warehouses and factories employed black men and women through World War II.

Today, the riverfront is a setting for recreation and enjoyment by all of Richmond’s residents. When the restored canals opened in 1999, among the dignitaries present was Douglas Wilder, a descendant of slaves, who as governor of Virginia from 1990 to 1994 was the first elected African American governor in the United States.

(captions)

Group of freedmen and children along the canal, c. 1865. Library of Congress

Background, black workers unloading railroad ties at Rockett’s Landing, 1928. Valentine Museum

Erected 2011 by Richmond Riverfront Canal Walk. (Marker Number 10.5.)

Topics. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: Abolition & Underground RR • African Americans • Bridges & Viaducts • Industry & Commerce. A significant historical year for this entry is 1800.

Location. 37° 31.935′ N, 77° 25.875′ W. Marker is in Richmond, Virginia. It is in Belle and Mayo Islands. Marker can be reached from the intersection of Canal Walk (U.S. 360) and South 17th Street, on the right when traveling west. This marker is on the Richmond Riverfront Canal Walk and the Richmond Slave Trail. Touch for map. Marker is at or near this postal address: 1401 Dock St, Richmond VA 23219, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. In a wooden crate similar to this one… (a few steps from this marker); Triple Crossing (within shouting distance of this marker); James River & Kanawha Canal (within shouting distance of this marker); Shockoe Slip (about 400 feet away, measured in a direct line); Early Shockoe (about 400 feet away); Lincoln's Visit to Richmond (about 400 feet away); Canal Walk / Historic Canals (about 400 feet away); Richmond Local Flood Protection (about 400 feet away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Richmond.

Also see . . .

1. Richmond’s Historic Canal Walk. Venture Richmond (Submitted on October 30, 2009.)

2. James River and Kanawha Canal Historic District. National Register of Historic Places (Submitted on October 30, 2009.)

Photographed By Bernard Fisher, October 25, 2009

6. Reproduction of the 3' x 2½' x 2' box used by Henry Brown.

"Details of Brown's escape, whereby he had himself shipped via Adams Express from Richmond to Philadelphia, were widely publicized in a narrative of his ordeal published under his own name in 1849. The box itself became an abolitionist metaphor for the inhumanity and spiritual suffocation of slavery." Library of Congress

Photographed By Bernard Fisher, April 21, 2011

7. Henry Brown quotes inscribed on the display

In a wooden crate similar to this one, Henry Brown, A Richmond tobacco worker, made the journey from slavery to freedom in 1849. “The idea flashed across my mind of shutting myself up in a box, and getting myself conveyed… to a free state.” “I laid me down in my darkened home of three feet by two.” “Buoyed up by the prospect of freedom…I was willing to dare even death itself.” “My friends…managed to break open the box, and then came my resurrection from the grave of slavery.” “I rose a free man.”

Photographed By Bernard Fisher, November 3, 2009

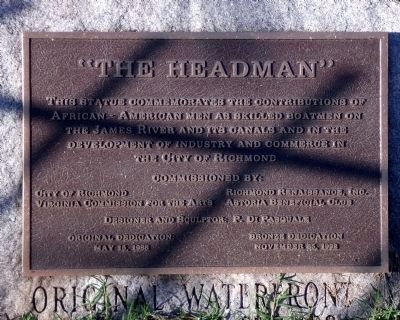

12. African Americans and the Waterfront

This statue commemorates the contribution of African-American men as skilled boatmen on the James River and its canals and in the development of industry and commerce in the City of Richmond. Commissioned by: City of Richmond, Virginia Commission for the Arts, Richmond Renaissance, Inc, Astoria Beneficial Club. Designer and sculptor: P. Di Pasquale. Original dedication: May 15, 1988. Bronze dedication: November 25, 1992.

Credits. This page was last revised on April 13, 2024. It was originally submitted on October 30, 2009, by Bernard Fisher of Richmond, Virginia. This page has been viewed 1,975 times since then and 60 times this year. Last updated on July 29, 2022, by Lou Donkle of Valparaiso, Indiana. Photos: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. submitted on October 30, 2009, by Bernard Fisher of Richmond, Virginia. 7. submitted on April 22, 2011, by Bernard Fisher of Richmond, Virginia. 8. submitted on October 30, 2009, by Bernard Fisher of Richmond, Virginia. 9, 10, 11. submitted on November 1, 2009, by Bernard Fisher of Richmond, Virginia. 12, 13. submitted on November 4, 2009, by Bernard Fisher of Richmond, Virginia.