Near McConnells in York County, South Carolina — The American South (South Atlantic)

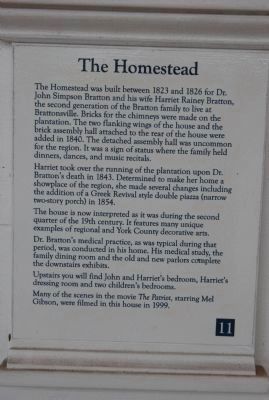

The Homestead

Harriet took over the running of the plantation upon Dr. Bratton's death in 1843. Determined to make her home a showplace of the region, she made several changes including the addition of a Greek Revival style double piazza (narrow two-story porch)in 1854.

The house is now interpreted as it was during the second quarter of the 19th century. It features many unique examples of regional and York County decorative arts.

Dr. Bratton's medical practice, as was typical during that period, was conducted in his home. His medical study, the family dining room and the old and new parlors complete the downstairs exhibits.

Upstairs you will find John and Harriet's bedroom, Harriet's dressing room and two children's bedrooms.

Many of the scenes in the movie The Patriot, starring Mel Gibson, were filmed in this house in 1999.

Topics. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: Agriculture • Architecture • Arts, Letters, Music • Entertainment • Settlements & Settlers. A significant historical year for this entry is 1823.

Location. 34° 51.888′ N, 81° 10.563′ W. Marker is near McConnells, South Carolina, in York County. Marker is on Brattonsville Road, 0.1 miles north of Percival Road, on the right when traveling south. Touch for map. Marker is in this post office area: Mc Connells SC 29726, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. Brick Kitchen (within shouting distance of this marker); Brattonsville (within shouting distance of this marker); A House of Untold Stories (within shouting distance of this marker); The Battle of Huck’s Defeat (about 300 feet away, measured in a direct line); Field of Huck's Defeat (about 300 feet away); William Bratton Plantation/Battle of Huck's Defeat (about 300 feet away); Backwoods Cabin (about 500 feet away); Bratton Home (about 600 feet away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in McConnells.

More about this marker. Marker is located on the front of the Homestead.

Additional commentary.

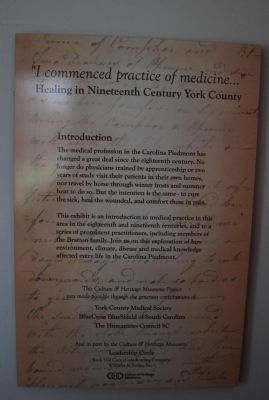

1. "I commenced practice of medicine..."

Healing in Nineteenth Century York County

Introduction

The medical profession in the Carolina Piedmont has changed a great deal since the eighteenth century. No longer do physicians trained by apprenticeship or two years of study visit their patients in their own homes, nor travel by horse through winter frosts and summer heat to do so. But the intention is the same - to cure the sick, heal the wounded, and comfort those in pain.

This exhibit is an introduction to medical practice in this area in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and to a series of prominent practitioners, including members of the Bratton family. Join us on this exploration of how environment, climate, disease, and medical knowledge affected every life in the Carolina Piedmont.

— Submitted November 28, 2009, by Michael Sean Nix of Spartanburg, South Carolina.

2. Medical Training

Learning the Healing Arts

Early Education for Physicians

In the 1700s and early 1800s, an aspiring physician in America took advantage of whatever formal education and training was available to him - local academies, institutes, colleges, and apprenticeships.

A man of means could travel within America or to Europe or England to study at an established medical school. Others entered apprenticeships with practicing physicians. A doctor's apprentice learned by reading popular medical texts of the day and observing the doctor at work. He gained "hand-on" skills and experience by assisting the doctor with diagnosing and treating cases. In time, the newly trained physician established his own practice, or continued to practice with his mentor.

Medical Colleges

The first medical college in America was founded at the University of Pennsylvania in 1765. Others followed in New York and Maryland, making medical education more easily available to American students.

Medical training for these early students consisted of 26 hours of classwork a week for four months each year for two years. Apprenticing with a physician between terms was considered an important part of a young doctor's training.

By the 1820s demand increased for a southern school of medicine, and in 1824, the Medical College of South Carolina was established in Charleston. The school was successful, and had 129 students in 1827. Other southern medical colleges followed quickly. The University of Virginia opened one in 1832, followed by others in New Orleans, Louisiana in 1835 and Richmond, Virginia in 1838.

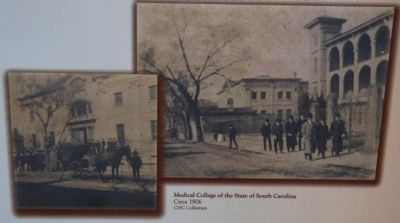

The Medical College of South Carolina was chartered by the state, was financed by its faculty, and was under the control of the Medical Society. The faculty came to resent limitations placed on them by the Medical Society, and in 1832 they resigned and established another school. Called the Medical College of the State of South Carolina, the new school opened its doors in Charleston with 105 students. The older school could not compete and closed in 1838.

States - Rights Medicine

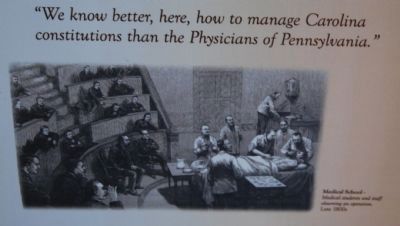

The establishment of Southern medical training schools was one result of a growing train of thought among doctors called "States - Rights Medicine."

Physicians felt that northern practitioners had no experience with or understanding of particular illnesses of the South, and that a patient accustomed to the southern climate, whether Caucasian or African American, needed to be treated differently than a patient in the North.

For decades, southerners who wished to become doctors traveled to Pennsylvania, New York, or Europe for their training; now they felt that a school that would focus directly on southern distinctiveness was in order. A North Carolina physician who had trained at the University of Pennsylvania sent his son to the same school for medical training. He acknowledged regional distinctiveness in a letter to his son: "We know better, here how to manage Carolina constitutions than the Physicians of Pennsylvania." Just as America was beginning to recognize differences in many aspects of life and government in the South, it was becoming acknowledged publicly in the world of medicine.

Healers and Home Remedies

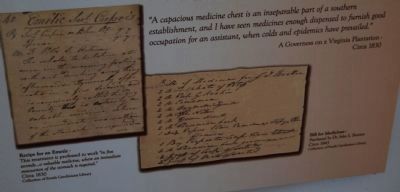

Trained physicians were scarce in the American colonies. Home health care was the only option available for many people. Some healers had little or no formal training. They learned traditional herbal remedies and treatments from other healers and family members.

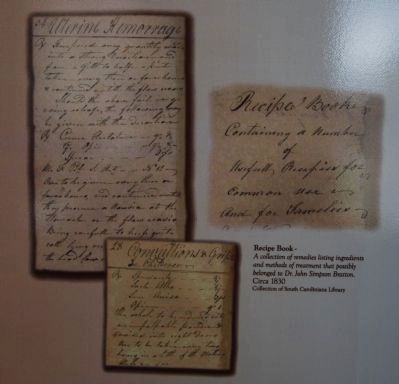

Just as in other areas in colonial America, those who settled in the Carolina Piedmont relied heavily on domestic treatment of diseases and injuries. Ancient practices, dooryard remedies, kitchen cures, and superstition blended with current medical theory in the Backcountry. Treatments for common ailments were handed down as family heirlooms, and usually involved medicinal herbs and plants. Housewives and plantation mistresses learned cures from older family members and acquired new knowledge by talking with neighbors and travelers, and reading newspaper, almanacs and domestic medical guides.

Settlers of Native American, African, English, Scotch-Irish, and German descent had different healing traditions, all of which were likely shared and mixed after several generations in America. Healers were constantly challenged to find new remedies as new infections and epidemics struck among Indians, settlers, and slaves alike.

— Submitted November 28, 2009, by Michael Sean Nix of Spartanburg, South Carolina.

3. Early Physicians

Healing in the Carolina Backcountry

Early settlers in the Carolina Piedmont relied heavily on home treatments of diseases and injuries. Family traditions, social customs and superstition often shaped accepted medical practices in the 1700s and 1800s. Home remedies and treatments were handed down from generation to generation in families, shared from neighbor to neighbor, and learned from home medical guides and newspapers. Medicinal recipes usually featured mixtures of garden herbs, local wild plants and roots, and purchased narcotic drugs and chemicals.

By the late 1700s, men with various degrees of medical training provided medical attention to others. Many of these men were primarily farmers or tradesmen who had apprenticed with another doctor, and had access to a medical dictionary or guide. Eventually more students sought out and received college or university training, and the medical profession in the Carolina Piedmont prospered.

Carolina Piedmont Physicians

Availability of trained physicians and medical care varied widely throughout the towns, plantations and remote settlements of the Carolina Piedmont. Historical documents, such as wills, estate inventories, censuses and family records, provide some insights into the practicing doctors and the medical services they provided to the citizens of the Carolina Piedmont from 1780 to 1900.

Reverend Dr. Joseph Alexander (1735-1809)

A native of Pennsylvania, Joseph Alexander graduated from Princeton College in 1760 and shortly after moved to North Carolina. In 1774, he settled in Bullock's Creek, South Carolina. Dr. Alexander was an eminent educator and established a classical school at Bullock's Creek in 1787. He organized churches in both North and South Carolina and preached until 1801. He then attended the College of South Carolina and received a Doctor of Divinity degree in 1807. According to an account of Major Joseph McJunkin's experiences in the Revolutionary War, the house of "Rev. Dr. Joseph Alexander... was a real Lazaretto [a hospital for contagious disease] for the sick and wounded of our army." Major McJunkin contracted smallpox while recovering from a wound at Alexander's home. According to Dr. Maurice A. Moore's writings in the 1860's, Rev. Alexander performed smallpox inoculations prior to 1796 at his home during an epidemic.

Dr. James Alexander

Dr. James Alexander also seems to have been involved in the treament and prevention of smallpox. D.A. Thompkins states in History of Mecklenburg County(1903): "In 1780, when the small pox epidemic was in the county, having been brought here by the British and the American armies, Dr. James Alexander vaccinated many of the people of his section. In one family he vaccinated ten persons, charging one pound currency for each 'innoculation'."

Battle of Huck's Defeat, July 1780

John Adair served as an officer during the American Revolution in the militia regiment of Colonel Edward Lacey and fought in the Battle of Huck's Defeat at Brattonsville. In 1839 he dictated an account of the battle to his son who fowarded the information to Dr. Maurice A. Moore in a letter: "Immediately after the battle my father was sent out by Coln. Lacy for a Doctor Turner who lived about a mile in the neighborhood, to attend to the wounded. He did not find Turner..." In 1859, Dr. Moore published The Life of Gen. Lacey which includes a description of the battle: "The battle lasted about one hour; the Whigs had one man killed, the British between thirty and forty killed, and about fifty wounded, who were billeted upon a few Tory families in the neighborhood, and attended by a Dr. Turner, who resided near the battle ground." In a footnote, Moore states, "The evening after the battle...some old ladies came in to administer to the sick and wounded."

Dr. Samuel Davies Alexander (1771-1855)

In his will, Rev. Joseph Alexander wrote: "...my Son Samuel has occasionally administered medicine & attended on me & family;..." and stated that his medical account had been previously settled.

Dr. Josiah Moore (1775-1807)

According to Dr. Maurice A. Moore, Josiah Moore attended Bullock's Creek classical academy and graduated from an institution in Kentucky. He studied medicine with Dr. McDowell of Danville, Kentucky and returned to South Carolina in 1803 to practice medicine in Yorkville. According to Moore, Josiah Moore was the first physician to settle in Yorkville.

Dr. David T. W. Cooke, "Quack" (1810)

A notice signed by prominent residents of York County area appeared in several southern papers in 1810. It announced: "On the night of the 20th of July last, Dr. David T. W. Cooke eloped from his place of residence in the district of York, South Carolina, where he had for some time attempted to palm himself on the public as a Physician and Surgeon...Immediately before his flight, Dr. Cooke, under specious but false pretenses, procured certificates, expressive of his medical adquirements, from several respectable citizens of this district..." The announcement also describes Cooke's rising debts, his patient wife and children, and his life of "idleness and wanton dissipation."

Dr. Maurice Augustus Moore (1795-1871)

A native of York County, Maurice Moore studied medicine in Wadesboro, North Carolina with Dr. William Harris and then took medical courses at the University of Pennsylvania. He returned to Yorkville and went into partnership with his brother Dr. William Moore(1791-1861), who had already established a practice. After his first wife died in 1826, he traveled to Cuba, as he believed the climate would restore his poor health. He remarried in 1833 and moved to Union County, South Carolina where he devoted himself to agriculture. His plantation, he felt, was subject to malarial fevers, and he soon began summering at Glenn's Springs in Spartanburg County, believing the water there to be therapeutic. In 1838 he and several others formed a stock company intending to develop the springs as a spa. The malarial season was too short to make the enterprise financially stable, but even after the company liquidated, Dr. Moore continued to welcome invalids and offer them the healing power of Glenn's Springs water.

Dr. Robert Hervey Hope (1818-1890)

A native of Cabarrus County, North Carolina, he graduated from the Medical College of the State of South Carolina in 1841. He first practiced medicine in the Bethesda community of York County and moved to Rock Hill in 1859. He is said to have been the first doctor to settle in Rock Hill. During the Civil War, Dr. Hope was released from service by the Confederate government to remain home and continue his practice.

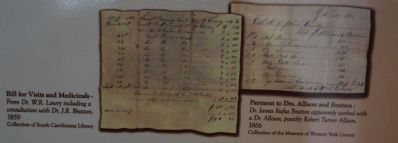

Dr. Robert Turner Allison (1798-1882)

A native of York County, he graduated from the South Carolina College in 1821 and from the Medical College of Lexington, Kentucky in 1825. Besides practicing general medicine, he farmed and ran a store at his Old Plantation on Clark's Fork Creek in western York County. Dr. Allison was active in politics and was elected to the State Legislature in 1838, serving two terms. He was also a member of the State Convention of 1860 that passed the Ordinance of Secession.

Dr. William Francis Strait (1854-1898)

A native of Chester County, Dr. Strait attended country schools in his community and studied medicine under his brother-in-law Dr. David Lyle and his uncles Drs. Alexander and William Wylie. He graduated from the Medical College of the State of South Carolina in 1876 and returned to practice medicine in Chester County. In 1890, Dr. Strait took a course in surgery in New York City. He then moved to Rock Hill and entered a partnership with Dr. Thomas A. Crawford. They rented a small house in Rock Hill to use as a hospital and performed surgeries there.

Dr. Thomas Allison Crawford (1854-1919)

A native of York County and nephew of Dr. Robert Hervey Hope, Dr. Crawford attended Kings Mountain Military School in Yorkville and continued his education in the medical department at the Central University of Kentucky, graduating in 1877. He set up practice in Rock Hill in 1878 and entered a partnership with Dr. William Francis Strait in 1891.

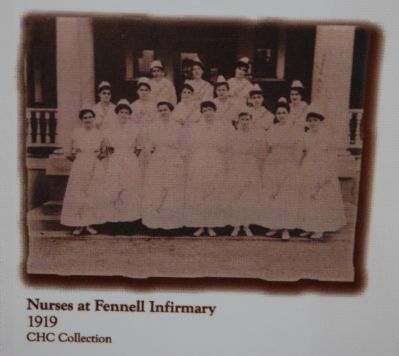

Dr. William Wallace Fennell (1869-1926)

A native of Chester County, William Fennell attended the Medical College of the State of South Carolina in Charleston. He later studied under the Mayo brothers of Rochester, Minnesota, and then studied in Europe for a year. Dr. Fennell returned to Chester County to begin his practice and about 1895 moved to Rock Hill. He established his first hospital around 1900, and in 1910 opened a training school for nurses and a hospital known as Fennell Infirmary. This facility was the only real hospital in York, Chester, Kershaw, and Fairfield counties at the time. As patients came a great distance, many by train, the Southern Rail Line established a stop at Confederate Avenue named "Fennell Infirmary Crossing". One description of the infirmary reads: "In a commodious two-story house, the doctor setup...fifty beds, a seperate ward for black patients, a dining room, a kitchen, and a laundry." Due to his declining health, Dr. Fennell leased the hospital to his assistant Dr. W.B. Ward in 1926. Dr. Fennell was recognized as a leader in his profession and he served in various medical organizations. His 1926 obituary states: "South Carolina's most noted surgeon and founder of the Fennell Infirmary, Rock Hill passed away at his residence..." Dr. Ward sold the hospital in 1935 and the name was changed to St. Phillips Hospital.

Minority Physicians in York County

During the Reconstruction era (1867-77) two schools offering medical education to African-American students opened - Howard Medical School in Washington, DC, and Meharry Medical School in Nashville, Tennessee.

Howard was open to all qualified applicants regardless of race or religion; but with a few exceptions, it functioned as an all African-American school. Meharry served only African Americans. Shortly thereafter, five or six other private African-American medical schools opened in the South. All but Howard and Meharry disappeared in the early 1900s when they were unable to meet rising medical school standards, but not before producing over a thousand physicians. Many of these physicians became licensed and practiced in African-American communities across the South.

Dr. J.O.G. Amble

A native of Nashville, Tennessee, and a graduate of Meharry Medical School, Dr. Amble came to Rock Hill in 1905 and left in 1908.

Dr. J.B. Russell

A native of Blackstock, South Carolina, and a graduate of Meharry Medical School, Dr. Russell practiced in Rock Hill from 1917 to 1930.

Dr. D.M. Duckette

A native of Union County, South Carolina, and a graduate of Meharry Medical School, Dr. Duckette came to Rock Hill in 1927.

Dr. I.A. Macon

A antive of Chester County, Dr. Macon attended Shaw University Medical College in Raleigh, North Carolina and practiced in Rock Hill from 1901 to 1927.

Dr. James Barber

A native of Chester County, Dr. Barber graduated from Shaw University Medical College and practiced in Rock Hill in 1904.

Dr. George W. Harry

A native of Spartanburg, South Carolina, Dr. Harry practiced in Rock Hill from 1904 to 1907.

— Submitted November 28, 2009, by Michael Sean Nix of Spartanburg, South Carolina.

4. Southern Health

Environments for Disease

The environment in which we live influences our lives in many ways today, a fact that was even more pronounced in the 1800s and 1900s. At the time, physicians acknowledged that cultural differences in diet, lifestyles, customs, and social interactions contributed to one's health and well-being. However, where one lived was believed by some to ultimately determine one's ability to stay healthy. The environment of the South was thought to have an especially strong impact upon one's health.

Medical Topography

The idea that people living in certain areas of the country are more susceptible to particular diseases has influenced medical thought for generations. By the 1800s, "Medical Topography" emerged as a field to study the relationship between disease and the landscape.

This discipline sought to understand geographic locations through the diseases they produced. Practicing medical topographers tried to record any environmental factors that might affect health in a particular place such as temperature, altitude, water quality, timing and amount of rainfall, wind direction, electrical air currents, soil types, the timing of fish runs, thunderstorms, hailstorms,and meteor showers. Although not all physicians believed in this theory, the opinion that the environment could create disease was generally accepted in medical practice and popular understanding.

Common Diseases in the South

The belief that the southern climate and environment was responsible for the outbreak of disease can be illustrated by three African diseases which spread rampantly through the Caribbean islands and to America by the importation of slaves - malaria, hookworm and yellow fever.

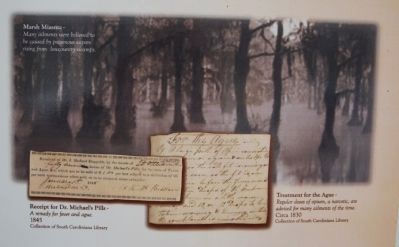

Malaria

A less deadly strain of malaria (vivax malaria) was imported to the Americas by early European settlers and flourished in the South, Northeast, and upper Midwest in the early to mid-1800s. Falciparum malaria, also called "fever" and "ague," was found in all parts of the Carolinas, along areas of undrained lands and waterways in the upper country. Malaria, a disease spread by mosquitos, brought on severe chills, high fever and intense thirst. Recovery from malaria provided a temporary immunity to the strain; but the disease recurred annually in many southerners. Because patients became accustomed to yearly attacks, they no longer considered it a significant illness.

Nevertheless, the impact of malaria on life and health was enormous; year after year it weakened the mental and physical strength of white southerners and increased their vulnerability to other diseases. Most African Americans had genetic immunity to vivax malaria and many were also immune to the falciparum malaria because of the sickle cell trait. But this immunity was not without cost as many African American children died from sickle cell disease.

Hookworm

Hookworm was a disease caused by a parasite, acquired by walking barefoot over contaminated soil and often associated with poverty and poor sanitation. Hookworms thrived in the South's moist warm sandy soils rich in humus. Like malaria, hookworm caused anemia and weakened the constitutions of many people.

Yellow Fever

Yellow fever, also spread by mosquitos, was introduced by ships from Africa traveling through the Caribbean to North America in the late 1600s. Characterized by high fever and jaundice(causing a yellow tint to the skin), yellow fever epidemics occurred in 1800, 1809, 1817, 1819, 1824, and for the last time in 1876. Although it caused many deaths among newcomers to America, if one survived yellow fever he was permanently immune to further infection. Africans and African Americans had some genetic resistance to the disease, and suffered lower mortality rates than white southerners.

Epidemics in South Carolina

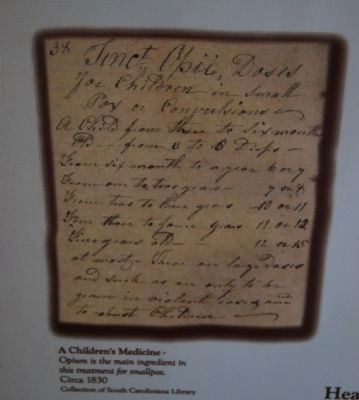

Other diseases flourished in the South's hot, humid climate. Smallpox, diphtheria, tuberculosis and a host of other deadly ills often spread epidemics throughout South Carolina in the 1800s.

Smallpox

Smallpox, a highly infectious disease causing fever, vomiting and skin eruptions was a frequent visitor to South Carolina before 1825. In the early 1800s it appeared sporadically over the whole state, and occurred as an epidemic in 1816. In 1860, several residents of York, as well as roughly 200 patients in Columbia suffered from smallpox. Another epidemic struck in 1897-1899 when more than 1,300 cases were reported statewide. Dr. Simon Baruch noted in 1880 that less than one-eighth of the state's population was vaccinated against smallpox.

Diphtheria

Diphtheria, marked by high fever and labored breathing, had long been a serious and extensive disease in South Carolina and continued to be a problem throughout the 1800s. Epidemics occurred in 1814 and 1881, and caused 544 deaths in 1888.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis, also called consumption, was increasingly prevalent in the mid to late 1800s. This disease, causing hard lumps in the lungs and body tissues, struck the African-American community particularly hard. In 1888, it was the cause of death in one out of every seven cases.

Other Common Diseases

Typhoid fever, diarrhea diseases, and digestive systems diseases, which spread through poor water supplies and sanitation, were common causes of mortality and ill health in the 1700s and 1800s.

Typhoid fever, marked by high fever and intestinal disorders, regularly attacked southerners during the summers throughout the 1700s. Dysentery, an inflammation of the intestines that brought fever, cramps, and diarrhea, was also very common. Influenza was active in South Carolina in 1807, 1815-1816, 1874-1875, 1886, and 1890-1891.

Environmental Effects on Disease

Physicians noted early on that diseases in the South were seasonal and seemingly related to annual changes in temperature, rainfall and atmospheric conditions.

Miasma

Physicians believed the danger came from the formation of "miasma" or "marsh poison" which occurred when vapors rose from rotting vegetation, stagnant water, and the soil itself. Miasmas were thought to be particularly dangerous near swamps or newly cleared farmland, especially at night. Miasma was not a disease itself but a quality of particular environments that encouraged the onset of disease. Miasma was believed to be responsible for many diseases such as malarial fevers (malaria in the original Italian means "bad air"), diarrhea, dysentery, diphtheria and yellow fever.

Because researchers did not link mosquitos to the spread of malaria until the late 1890s, it remained a health problem until the early 1900s. The spread of yellow fever was attributed to mosquitos in 1900. As man altered the environment by draining swamps, introducing agriculture and building towns, physicians observed a general improvement of health. Health officials in the early 1900s urged efforts to clean up the environments where flies bred and to fight mosquitos by draining marshy grounds.

Health in the Carolina Piedmont

Although many of the diseases that affected the lowcountry residents were also present in the Carolina Piedmont, this area was considered more "salubrious" or healthier than coastal areas or the mountains.

The Carolina Piedmont's shorter summers gave intestinal diseases less time to flourish, and temperatures were generally too cool for falciparum malaria to develop in the mosquito population, so only the milder vivax variety afflicted residents. The heavy soils prevented hookworm proliferation and yellow fever was not common.

Colder, longer winters in the mountains meant that respiratory diseases could be serious there; but in general, the Piedmont was considered favorable to good health. In 1775, Rev. William Tennent wrote in his journal of the difference between the lowcountry and the Backcountry: "Set off with Mr. Harris for his house, passed by Mr. Bowie's, crossed Little River. The land here appears extremely fine, arrived at our Quarters at sundown 16 miles. Found good Mrs. Harris down with the ague (malaria), as more or less of every family seems to be in this quarter. Could not help observing the difference between the health of this district and that between Broad and Catawba Rivers."

— Submitted December 3, 2009, by Michael Sean Nix of Spartanburg, South Carolina.

5. Diseases and Therapies

Southern Distinctiveness

The belief that people who lived the South were exposed to different diseases than northern people, and that the very environment and climate of the South called for different therapies for these illnesses was a strong component of States-Rights Medicine.

Southern physicians believed the hot, humid climate, miasma (poisonous vapors) around swamps and rivers, diet, dress, work habits, class structure and the higher numbers of African Americans all contributed to the diseases experienced by southerners. Northern practitioners agreed. Benjamin Rush, one of the most well-known and well-respected physician-professors at the University of Pennsylvania stated certainly, "Diseases of warm and cold climates require different treatment."

Southern "Seasoning"

Malaria was arguably the most common southern disease in the 1800s. Although known in the northern states, it was so widespread in the South that it was regarded as a natural part of life.

Found to be more prevalent in lowcountry swamps and coastal plains, malaria was believed to be spread by marsh miasma. Contracting malaria within the first year of immigrating to the South was considered the "seasoning" one needed to become acclimated to the hot, humid climate.

Symptoms of malaria and other diseases - fever, chills, dysentery - drained a patient of strength and vitality. A broad range of therapies was administered to ease a patient's discomfort. However, the accepted treatments and medications of the time had little effect on the actual bacterial and viral origins of these diseases. In fact, these therapies likely served to further weaken a patient's natural defenses to illness, leaving him susceptible to new infections and outbreaks of diseases.

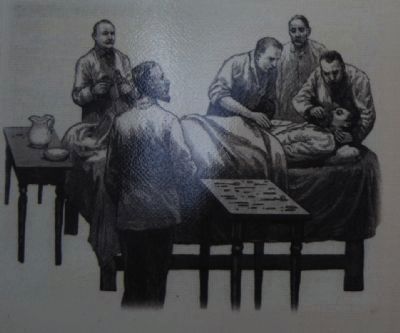

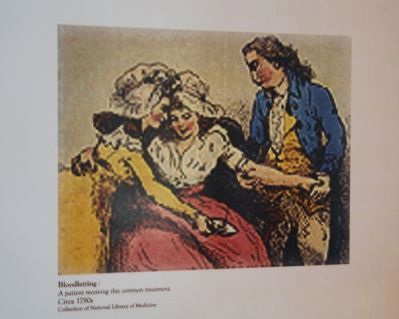

Therapies

In the 1800s and 1900s, most physicians believed that a disease could be treated successfully by treating its symptoms. Any therapy that eased the violence of the symptoms would be considered effective against the disease. Two kinds of therapies were most commonly called upon to offer this short-term relief - blood letting, and cathartics.

Bloodletting (cutting a vein in the patient to allow blood to flow out) was a highly regarded treatment and nearly always used for fever, wounds, burns, bruises and fractures. The effects were often dramatic; one nineteenth-century doctor wrote "Often within ten to twenty minutes after faintness or sickness occurred the subject of [bloodletting] would become bathed in a copious perspiration, and the violent fever and delirium existing a short time before would have entirely passed away." Since bloodletting temporarily relieved the patient's symptoms, the treatment was considered successful. Rather than curing and strengthening the patient, however, it often left them weak and unable to fight the underlying disease.

Cathartics, including purgatives (which induced vomiting) and emetics (which stimulated the bowels) were also very important component's in the doctor's bag. Used to clean out the patient's digestive tract, the drugs or herbs prescribed created a drastic and immediate response. The force of the cleaning and the temporary relief of symptoms convinced patient and doctor alike that the therapy was effective.

The use of bloodletting and cathartics in the South was somewhat different than in the North. Bloodletting was considered less effective by southern practitioners: "the loss of much blood is not so well borne, nor its curative influence to favorably exerted in this as in Northern climates." It was thought that the southern constitution reacted better to larger doses of certain drugs than those in the North. Because fevers tended to be recurrent in the southern climate, practitioners felt that quinine (made from the bark of the tropical cinchona tree) should be given freely. When another attack was suspected, larger doses of the medicine were prescribed. In like manner, large doses of calomel, the most common and popular purgative, were recommended often to patients. A positive side effect, many believed was that calomel (a tasteless powder of mercury-chloride) stimulated the liver. Malaria and the intense southern heat were thought to be damaging to the liver. So calomel was given "in the treatment of the diseases of the South generally...because the liver is virtually the 'scapegoat' for almost all the affections of the other organs...in Southern lattitudes." It was thought by some that calomel was "required to be administered in doses nearly twice as large in the South as in the North" to create the same therapeutic benefit. Other stimulating and fiery remedies, such as lobelia and cayenne pepper, were also thought to be particularly effective against southern diseases.

Breeding Grounds for Disease

The institution of slavery as it was practiced in the South created breeding grounds for disease that were difficult for any amount of therapy to conquer. Slaves used traditional remedies, although many owners preferred that plantation mistresses or visiting doctors treat ailments and injuries.

Respiratory illnesses ran rampant through slave quarters in the winter. During colder months and bad weather, slaves were forced to spend considerable time indoors in close contact with family and friends who may have contracted tuberculosis, diphtheria, colds and upper respiratory infections, influenza, pneumonia and streptococcal infections. Whooping couch, measles, chicken pox and mumps were also common and could prove fatal. In warmer weather, intestinal diseases caused by poor sanitation and close contact with the earth became prevalent, especially maladies of the digestive tract and various "fevers." Rural white families without slaves were subject to the same illnesses, but due to their isolation, these might have remained a personal health problem, not one that affected an entire community.

— Submitted December 3, 2009, by Michael Sean Nix of Spartanburg, South Carolina.

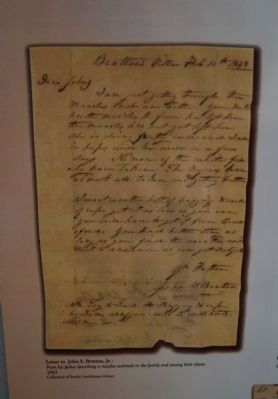

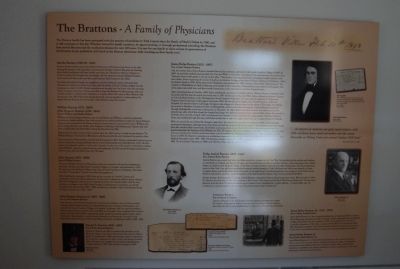

6. The Brattons

A Family of Physicians

The Bratton family has been associated with the practice of medicine in York County since the Battle of Huck's Defeat in 1780, and it still continues to this day. Whether trained by family members, by apprenticeship, or through professional schooling, the Brattons have served this area and the medical profession for over 200 years. It is rare for any family to claim at least six generations of involvement in any profession. Let's look at the Bratton physicians while traveling up their family tree.

Martha Bratton (1749/50-1816)

Bratton family tradition states that Martha Robinson (or Robertson) was born on the ship bearing her parents to the America colonies from Northern Ireland. She grew up learning about herbal medicines and home health care from her Ulster-Scots elders in Virginia or North Carolina. She brought that knowledge with her when she married William Bratton and moved with him to the area that would become York County in the 1760s.

She likely doctored her family, her neighbors, and her husband's slaves. One story that illustrates her talents as a healer took place after the Battle of Huck's Defeat, fought near her homestead on July 12, 1780. British casualties were brought into her house after the morning battle. It appears that most of them were able to leave the Brattons by that evening, with one notable exception. Captain John Adamson, a Loyalist officer who came to Mrs. Bratton's aid the previous day, fell off his horse during the battle and was impaled on a pine sapling. He stayed with the Bratton's for several days, while Martha nursed his wound.

William Bratton (1773-1850)

John Simpson Bratton (1789-1843)

Sons of William and Martha Bratton

William and John Simpson Bratton, two sons of Martha and William, worked as physicians. According to family tradition, they both trained in the medical profession under Dr. James Simpson. Simpson was connected to the Bratton family in several ways; he was married to Jane, William and John's sister, and was a son of Rev. John Simpson of Fishing Creek Presbyterian Church, who had been a rebel leader with their father during the Revolutionary War.

William lived in York County until sometime after the 1800 census, in which he was listed as "Dr. William Bratton." He moved to Winnsboro with his second wife, and continued his

Photographed By Michael Sean Nix, November 14, 2009

27. Medical Equipment

Advancements in 19th century medical science not only improved treatments and medications but also medical equipment. Equipment, like this wheelchair, often improved the quality of life for many of the those afflicted by illness and coping with the effects of a debilitating disease. This wheelchair was used by Mattie Oates Macdonald of Blackstock, South Carolina in the late 1800s. Mattie developed chronic osteomyletis (a painful bone infection) of the knee in her late teens. This chair was acquired from an old hospital by her husband and shipped via train from Columbia, South Carolina to Blackstock.

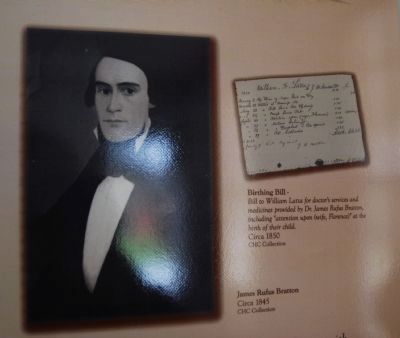

John remained at Brattonsville, and built the Homestead in 1823. He was a successful business man as well as a physician, having established stores at both Brattonsville and Yorkville(now York). He lent money and extended credit to a wide circle of people. At the time of his death, he held debts totaling nearly $50,000 - many for medical service and treatments. He also owned the largest plantation in York County, with over 6000 acres and 139 slaves.

John Bratton (1831-1898)

Son of William Bratton

The son of William Bratton of Winnsboro, John was schooled at Mt. Zion Institute in that town. He then attended South Carolina College at Columbia, and graduated in 1850. He went on to the Medical College of the State of South Carolina at Charleston. His thesis was titled "Fecundation" (studies of fertility and pregnancy).

After finishing his training in 1854, John set up a practice in Fairfield County, and continued to farm his father's plantation. He also had an illustrious military career, rising to the rank of Brigadier General in the Confederate Army. He entered politics after the war, serving as a delegate to the 1865 South Carolina Constitutional Convention, as a South Carolina State Senator from 1865-1866, and then as a member of the United States House of Representatives from 1883-1885.

John Simpson Bratton, Jr.

Son of John Simpson Bratton

John Simpson and Harriet Rainey Bratton had fourteen children, three of whom studied medicine. John Simpson Bratton, Jr. attended Mt. Zion Institute in Winnsboro, and probably the South Carolina College in Columbia. In January, 1843, he and his brother J. Rufus studied anatomy with Dr. Fair and Wells in Columbia. They completed their study in April, just before their father's unexpected death. Instead of starting medical school, John remained in Brattonsville to run the family plantation and businesses. He and his wife Harriet Jane Rainey Bratton built Forest Hall (now known as Hightower Hall) in 1854-1856.

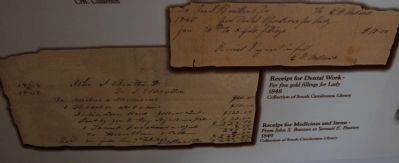

Samuel E. Bratton (1820-1893)

Son of John Simpson Bratton

Samuel E. Bratton was able to continue his education at the Medical College of the State of South Carolina after his father's death. He graduated in 1844, after writing a thesis on dysentery. He worked as a physician in York County, and married Laetitia Alison Torrance, the daughter of a prominent Mecklenburg County planter in 1847. They moved to Georgia in 1859.

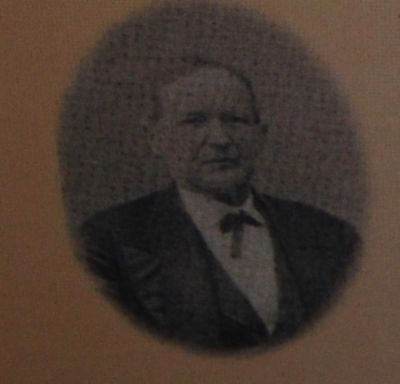

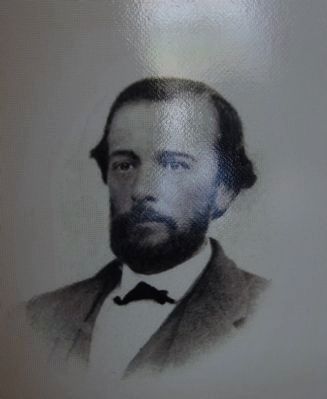

James Rufus Bratton (1821-1897)

Son of John Simpson Bratton

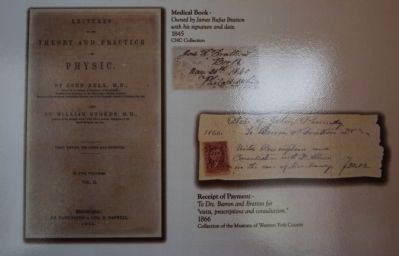

Like his brother John, Rufus Bratton attended Mt. Zion Institute, and went to the South Carolina College in 1840. In 1843, he and John studied anatomy with Dr. Fair and Wells in Columbia. According to reminiscences, the doctors had dissectory rooms in their garden in the rear of their office." The Bratton boy returned home, intending to study medicine with their father, before beginning the course of study at the Medical College of the State of South Carolina at Charleston. After his father's death in 1843, Rufus went to Charleston and graduated in 1845, writing a thesis titled "Menstruation." He traveled to Philadelphia in April of that year, and studied at the University Pennsylvania and worked in its hospital. Two of his sisters went with him, and they traveled extensively in the Mid-Atlantic and New England states.

After returning home in October, 1845, Rufus established a practice in Yorkville with Dr. William Moore. Unsatisfied with his profits in the first year, he struck out on his own in 1847. At the start of the Civil War, Rufus enlisted as Assistant Surgeon to Colonel Micah Jenkins of the 5th Regiment, South Carolina Volunteers. He went with his regiment to Richmond, Virginia where he became a full surgeon in January 1863. He was placed in charge of the Fourth Division of Winder Hospital. He was sent to LaGrange, Georgia to take charge of a division there for the Army of the Tennessee. By 1864, he was posted to Madison, Georgia and then to Milledgeville, where he was the post surgeon. General Sherman marched through Milledgeville on his way to Savannah on November 19, 1864. Rufus and other doctors were taken prisoner for several days, after which they closed the hospital and began the difficult journey home to await further orders. He arrived in Yorkville about the 9th of April, 1865, and learned that General Lee had surrendered at Appomattox. President Jefferson Davis was traveling through the area, and Rufus invited him to stay for a night at his home on Congress Street in Yorkville.

With the end of the war, Rufus' life changed a great deal. He resumed the practice of medicine in 1866, and continued running his plantation, although most of his slaves had left the property after emancipation. In response to perceived threats from the now-free black community, Dr. Bratton and many others joined the Klu Klux Klan. Because he was wanted for questioning after the lynching of Jim Williams in 1871, Dr. Bratton fled first to Alabama, and then to London, Ontario. His wife and several of his children joined him there, and he established a thriving medical practice. They were able to return home in 1878, Dr. Bratton's reputation as a physician remained strong, and he severed as the President of the South Carolina Medical Association from 1891-1892. He became a member of the Executive Committee of the State Board of Health in 1881. He was elected Chairman in 188, and held that office until his death in 1897.

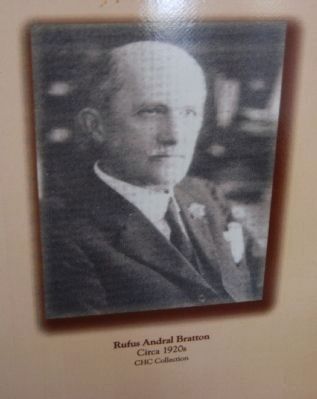

Rufus

Photographed By Michael Sean Nix, November 25, 2009

31. Medicine Chest

Small chests like these were used by doctors when making house calls to carry and protect their medicines. This example still has its original bottles, some of them with labels from Charleston, South Carolina, pharmacies. The Brattons who trained at the Medical College of the State of South Carolina were probably very familiar with chests like this one.

Son of James Rufus Bratton

Andral Bratton was a small boy when his father served as surgeon in the Civil War. He traveled with his mother and brothers to visit Rufus in Virginia and later in Georgia, and lived with them in exile in London, Ontario. Upon returning to the United States, he studied at the Medical College of the State of South Carolina, where he was class valedictorian. He did post-graduate study in New York City, and then established a general medical practice in York. His home and office were located on South Congress Street, next to the Rose Hotel. He served on the state board of medical examiners, was president of the York County Medical Association, and was a medical member of the draft board for western York County during World War I.

Besides having a thriving medical practice, Andral Bratton continued to farm on land located near York. When he died in 1942, Dr. Bratton was described as "the oldest physician in York County." His obituary in Rock Hill Evening Herald read, "He was truly a physician of the old school. He practiced medicine not as a means to earn a livelihood but to relieve suffering - to help his fellow man. He considered not a person's station in life or his race if that person stood in need of medical aid."

Lawrence Bratton

Son of Samuel E. Bratton

Lawrence

Photographed By Michael Sean Nix, November 25, 2009

32. Cupping Glass

Cupping glasses such as this one were used to blister a patient's skin, drawing blood away from the site of an illness or infection to the skin where it could be released. After heating the cup, the doctor applied it to the patient, where the suction of the hot air inside the cup drew blood to the surface, producing a red and swollen area on the body. The suction was broken, and often the blister was opened with a lancet or scarificator, allowing the blood to escape. Symptoms and diseases thought to be cured or lessened by cupping included inflamed joints, coughs, breathlessness, headaches, sore throat, cramps, lunacy and convulsions.

James Rufus Bratton, Sr. (1913-1979)

Son of Rufus Andral Bratton

James Rufus Bratton, Sr. was a popular pediatrician, serving Rock Hill for 39 years. His college years were spent at Duke University, and he graduated from the Medical College of the State of South Carolina in 1937. He completed his residency in Louisville, Kentucky in 1940. After serving in World War II, he returned to Rock Hill. He became president of the South Carolina Pediatrics Society, and was active in the York County Medical Society as well as the American Medical Association.

James Rufus Bratton, Jr.

Son of James Rufus Bratton, Sr.

James Rufus Bratton, Jr., is the last Bratton physician in the Carolina Piedmont. Like so many of his ancestors Rufus attended the Medical College in Charleston, now known as the Medical University of South Carolina. After completing his residency in Charleston, Dr. Bratton established a practice specializing in ears, nose and throat in Florence, South Carolina.

— Submitted December 6, 2009, by Michael Sean Nix of Spartanburg, South Carolina.

Photographed By Michael Sean Nix, November 25, 2009

33. Scarifier

Scarifiers were one tool used to open a patient's veins for bloodletting. Small blades were secured inside the instrument. The doctor would place the scarifier against the skin, release the blades with a lever and make a series of quick, neat cuts. The blood was usually collected in a bowl. Other instruments used for the same purpose were called fleams and lancets. Leeches were also widely used for bloodletting.

Photographed By Michael Sean Nix, November 25, 2009

34. Medical Bag

Dr. Thomas Boyd Meacham (1836-1908) was a native of Jackson, Tennessee, who graduated from the Medical College of South Carolina in 1860. He enlisted in the Confederate Army in 1861 serving as Captain of Company E in the 17th Regiment of South Carolina Volunteers. The Company was reorganized in the spring of 1862 and Dr. Meacham returned to Rock Hill. After the war he opened the Fort Mill Drug Company, the first drug store in Fort Mill. He also practiced medicine in York County. He sold the drug store to J.R. Haile in 1907. He is listed on the 1860 Federal Census of York County as a physician.

Credits. This page was last revised on February 3, 2020. It was originally submitted on November 27, 2009, by Michael Sean Nix of Spartanburg, South Carolina. This page has been viewed 2,925 times since then and 43 times this year. Photos: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43. submitted on November 27, 2009, by Michael Sean Nix of Spartanburg, South Carolina. 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54. submitted on November 28, 2009, by Michael Sean Nix of Spartanburg, South Carolina. 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61. submitted on December 3, 2009, by Michael Sean Nix of Spartanburg, South Carolina. 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67. submitted on December 6, 2009, by Michael Sean Nix of Spartanburg, South Carolina. • Kevin W. was the editor who published this page.