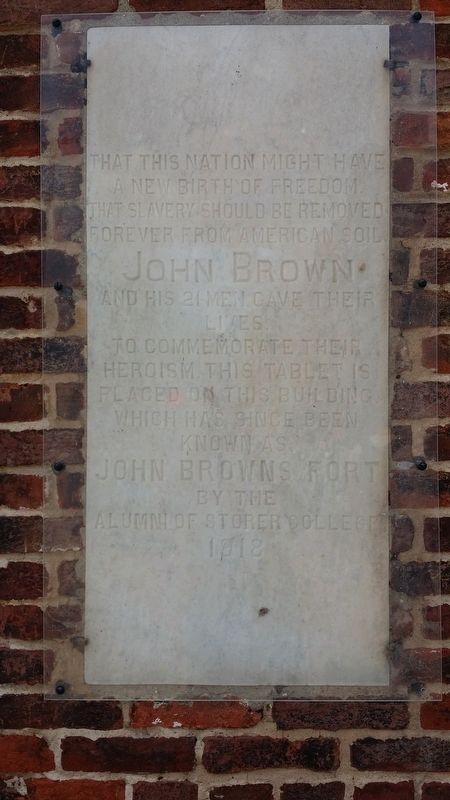

Harpers Ferry in Jefferson County, West Virginia — The American South (Appalachia)

John Brown

a new birth of freedom,

That slavery should be removed

forever from American soil.

John Brown

and his 21 men gave their

lives.

To commemorate their

heroism, this tablet is

placed on this building,

which has been

known as

John Brown's Fort

by the

Alumni of Storer College

1918

Erected 1918 by Alumni of Storer College.

Topics and series. This memorial is listed in these topic lists: Abolition & Underground RR • African Americans • War, US Civil. In addition, it is included in the Historically Black Colleges and Universities series list. A significant historical year for this entry is 1859.

Location. 39° 19.387′ N, 77° 43.777′ W. Marker is in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, in Jefferson County. Memorial is at the intersection of Shenandoah Street and Potomac Street on Shenandoah Street. Touch for map. Marker is at or near this postal address: 814 Potomac St, Harpers Ferry WV 25425, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. "The War That Ended Slavery" (here, next to this marker); Federal Armory (here, next to this marker); Weapons Under Fire (a few steps from this marker); A Nation's Armory (a few steps from this marker); John Brown Fort (within shouting distance of this marker); Large Arsenal (within shouting distance of this marker); Large Arsenal Foundation (within shouting distance of this marker); John Brown Monument (within shouting distance of this marker). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Harpers Ferry.

More about this marker. Marker was apparently originally erected in 1918, attached to the structure itself, which has been moved since. It was moved to current site in 1968.

Regarding John Brown. Movements and history of the building:

1848: Built as fire engine house for U. S. Armory.

1859: Serves a stronghold for John Brown and his raiders.

1861-1865: Escapes destruction during Civil War (only armory building to do so), but is vandalized by souvenir-hunting Union and Confederate soldiers and later travelers. Name "John Brown's Fort" painted on it, one word over each door.

1891: Dismantled and transported to Chicago Exposition.

1895: Rescued from conversion to stable and brought back to Harpers Ferry area; no better location than a farm was available. Original locstion had been covered by a railroad embankment.

1909: Purchased by Storer College (a totally Black, segregated college) and moved onto campus.

1968: Moved by National Park Service to within 150 feet of its original location.

Source: Interpreting Sacred Ground: The Rhetoric of National Civil War Parks and Battlefields p. 65 (link to book on this page)

Visitors to Harpers Ferry should be aware than John Brown is a sensitive topic; he was no hero in Harpers Ferry.

Related markers. Click here for a list of markers that are related to this marker. To better understand the relationship, study each marker in the order shown.

Also see . . . Interpreting Sacred Ground: The Rhetoric of National Civil War Parks and Battlefields.

From chapter 2 of the book:

The Storer memorial connects Brown's raid to the ongoing, abstract pursuit of "black freedom," avoiding the more finite language of "black emancipation," which would have suggested that Brown and his raiders' sacrifices had been redeemed through the Fourteenth Amendment.

...Storer's plaque can also be read as a fragment of a larger emancipationist memory. The popular origins of the emancipationist vision and its emphasis on national rebirth through renewed commitment to racial equality are commonly tied to Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, a more sanitized route for African Americans to secure approval for what was then a radical cause. The first two lines of the Storer plaque are therefore very typical, borrowing directly from Lincoln's address the key passages that encouraged a rebirth of racial equality. (Submitted on November 11, 2016, by Michael C. Wilcox of Winston-Salem, North Carolina.)

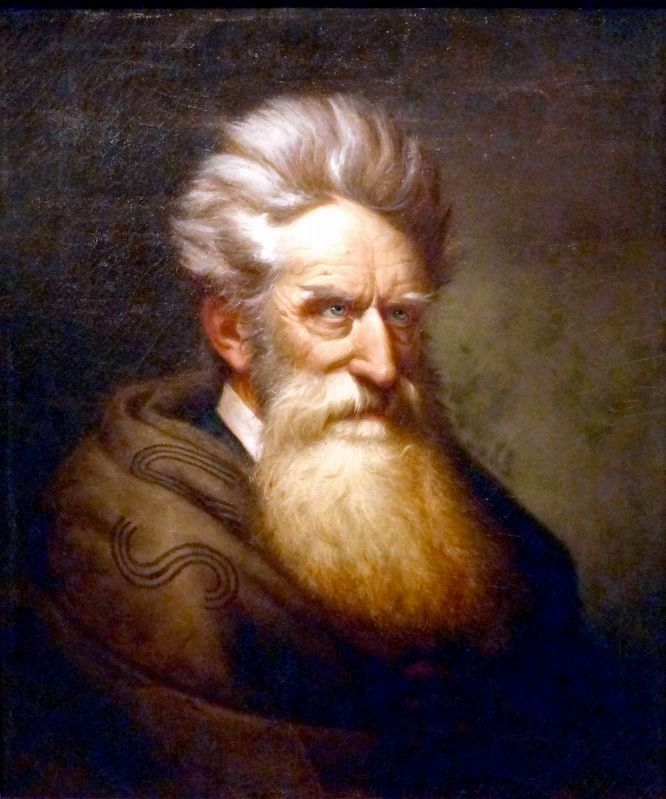

4. John Brown 1800-1859

This 1872 portrait of John Brown by Ole Peter Hansen Balling hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC.

“There were those who noted a touch of insanity in abolitionist John Brown; he believed he had been called by God to embark on a personal crusade to end slavery. Brown and five of his sons were actively engaged in the bloody guerrilla war being waged in Kansas in 1855-56, between proslavery and antislavery factions. But in 1857, Brown began making plans for the 1859 raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, an event that would make him both infamous and immortal. The scheme to commandeer firearms with which to arm a slave rebellion failed, and Brown was captured, tried, and hanged. His insurrection found favor among many northern abolitionists. In response, southerners viewed Brown as a sign that they must either break their allegiance to the Union or be destroyed by an increasingly fanatical North.” — National Portrait Gallery

“There were those who noted a touch of insanity in abolitionist John Brown; he believed he had been called by God to embark on a personal crusade to end slavery. Brown and five of his sons were actively engaged in the bloody guerrilla war being waged in Kansas in 1855-56, between proslavery and antislavery factions. But in 1857, Brown began making plans for the 1859 raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, an event that would make him both infamous and immortal. The scheme to commandeer firearms with which to arm a slave rebellion failed, and Brown was captured, tried, and hanged. His insurrection found favor among many northern abolitionists. In response, southerners viewed Brown as a sign that they must either break their allegiance to the Union or be destroyed by an increasingly fanatical North.” — National Portrait Gallery

Credits. This page was last revised on March 3, 2021. It was originally submitted on November 11, 2016, by Michael C. Wilcox of Winston-Salem, North Carolina. This page has been viewed 671 times since then and 41 times this year. Last updated on March 3, 2021, by Daniel Eisenberg of Boca Raton, Florida. Photos: 1, 2, 3. submitted on November 11, 2016, by Michael C. Wilcox of Winston-Salem, North Carolina. 4. submitted on November 11, 2016, by Allen C. Browne of Silver Spring, Maryland. • Devry Becker Jones was the editor who published this page.