Hugo in Lincoln County, Colorado — The American Mountains (Southwest)

Hugo Country

Sand Creek Massacre

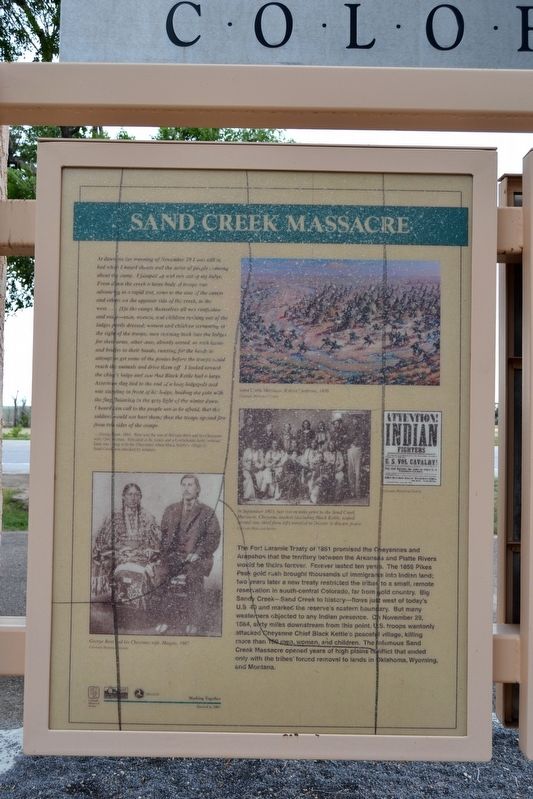

At dawn on the morning of November 29 I was still in bed when I heard shouts and the noise of people running about the camp. I jumped up and ran out of my lodge. From down the creek a large body of troops was advancing at a rapid trot, some to the east of the camps and others on the opposite side of the creek, to the west ... [I]n the camps themselves all was confusion and noise - men, women, and children rushing out of the lodges partly dressed; women and children screaming at the sight of the troops; men running back into the lodges for their arms, other men, already armed, or with lassos and bridles in their hands, running for the herds to attempt to get some of the ponies before the troops could reach the animals and drive them off. I looked toward the chief's lodge and saw that Black Kettle had a large American flag tied to the end of a long lodgepole and was standing in front of his lodge, holding the pole with the flag fluttering in the grey light of the winter dawn. I heard him call to the people not to be afraid, that the soldiers would not hurt them; then the troops opened fire from two sides of the camps.

— George Bent, 1864. Bent was the son of William Bent and his Cheyenne wife, Owl Woman. Educated in St. Louis, and a Confederate Army veteran, Bent was living with the Cheyennes when Black Kettle's village on Sand Creek was attacked by soldiers.

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 promised the Cheyennes and Arapahos that the territory between the Arkansas and Platte Rivers would be theirs forever. Forever lasted ten years. The 1859 Pikes Peak gold rush brought thousands of immigrants into Indian land; two years later a new treaty restricted the tribes to a small, remote reservation in south-central Colorado, far from gold country. Big Sandy Creek - Sand Creek to history - flows just west of today's U.S. 40 and marked the reserve's eastern boundary. But many Westerners objected to any Indian presence. On November 29, 1864, sixty miles downstream from this point, U.S. troops wantonly attacked Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle's peaceful village, killing several hundred men, women, and children. The infamous Sand Creek Massacre opened years of high plains conflict that ended only with the tribes' forced removal to lands in Oklahoma, Wyoming, and Montana.

(Top Image Caption)

Sand Creek Massacre, Robert Lindneux, 1936

(Center Image Caption)

In September 1864, just two months prior to the Sand Creek Massacre, Cheyenne leaders (including Black Kettle, seated second row, third from left) traveled to Denver to discuss peace.

(Bottom Image Caption)

George

Bent and his Cheyenne wife, Magpie, 1867

Stagecoach Travel

Smoky Hill Stage Station

David Butterfield had a sound reason for running his stagecoach line over the Smoky Hill Trail: It was the fastest, most direct route from Kansas City to Denver. But it was also the most dangerous — an isolated, undefended road that passed right through the heart of Cheyenne lands. The only stops along the way, Butterfield's lonely stage stations, were mini-fortresses of earthen trenches and clustered sod walls. The stations stood at roughly fifteen-mile intervals, with three of them in this vicinity — one very near here, another just east of present-day Hugo, and one at Hedinger's Lake, near Limon. Butterfield opened the line in 1865, at the height of the Indian Wars, and his stages quickly became favorite targets. Discouraged and losing money, he sold the operation to Ben Holladay in 1866.

Passengers on the Butterfield Overland Despatch (B.O.D.) stood a better-than-even chance of surviving the trip; that was the good news. The bad news was that they had to spend days on end in cramped, stuffy quarters, bouncing over punishingly uneven roads in a spray of slush, dust, and mud. Occasionally they rattled past the scene of a day-old Indian attack, the corpses still lying in the field. Though Butterfield used handsome Concord coaches—the most comfortable, smoothest-riding carriages of their day—this was a miserable journey in every respect, including the price ($75 one way from Kansas City to Denver). But travelers had no better option. Between 1859 and the opening of the Kansas Pacific Railroad in 1870, the B.O.D. and other stagecoach lines brought thousands of passengers out West.

(Top Image Caption)

Wells, Fargo & Company bought Ben Holladay's Overland Mail & Express Company—which ran over the Smoky Hill Trail—in 1866 and gained a near-monopoly in the western stagecoach business.

(Center Image Caption)

Throughout the late1860s Smoky Hill stage stations were constantly under siege by Indian attackers, as shown in this 1866 Harper's Weekly Magazine illustration.

(Bottom Image Caption)

David A. Butterfield, 1860s

From Horse to Tractor

The settlement of eastern Colorado in the late 1800s coincided with a breakthrough in farming technology: the steam tractor. These remarkable devices could do the work of thirty horses, enabling tasks that once took weeks to be completed in days. Though too cumbersome and expensive for widespread use, they demonstrated the potential of mechanized agriculture and thus planted the seeds of progress. When gas-driven tractors appeared after 1900, they quickly uprooted the harness and plow. Farmers were able to keep fewer working animals on hand and tie up less of their acreage in pasture; they also saw less of their neighbors, as communal work patterns gave way to the impersonal labor of pistons and gears. But the transition brought clear gains in productivity and prosperity. By 1940, most Colorado farms were fully mechanized.

Rural Electrification

Long after American cities were wired for electricity, many families in these remote prairies were still living by candlelight. The region's vast distances and meager customer base scared big power companies off. Even Hugo, which raised the funds to build its own electric plant in 1921, could not afford to stretch its service beyond the city limits. Nearby farmers and ranchers had to make do with improvised wind-powered generators, producing just enough voltage to run a sewing machine or a radio. In 1936 the Rural Electrification Administration finally began providing aid to unplugged areas, but while the paperwork pended and the grid was laid down, another generation grew up in the dark. The currents didn't flow to this countryside until 1951, making it one of the last parts of the nation to enter the electric age.

(Top Image Caption)

Appliances like this electric range—available by the early 1910s—may not have removed all the drudgery from household chores, as some advertisers claimed, but they certainly required less labor than their coal-burning predecessors.

(Center Images Caption)

Though today they are rarely used to generate power, windmills continue to serve ranchers and farmers by pumping water for cattle and irrigation.

(Bottom Image Caption)

Despite their obvious advantages, steam tractors caused serious problems. Sparks emitted from the tractor's smokestack might set entire fields ablaze.

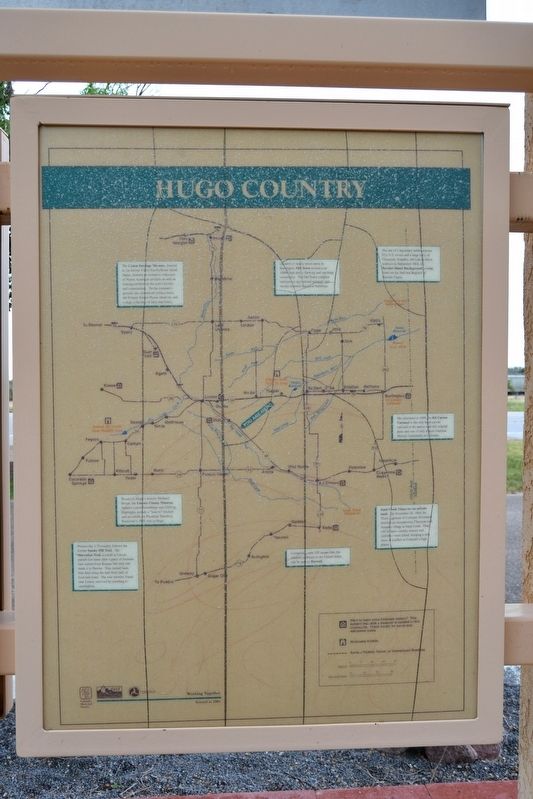

Hugo Country

• The Limon Heritage Museum, located in the former Union Pacific/Rock Island Depot, features an extensive collection of Native American artifacts as well as rotating exhibits on the area’s history and communities. On the museum’s grounds are old railroad rolling stock, the Pioneer School House Museum, and a large collection of farm machinery.

• Located on nearly seven acres in Burlington, Old Town recreates an 1890s high plains farming and ranching community. The Old Town complex includes an agricultural museum and twenty restored historical buildings.

• The site of a legendary battle between fifty U.S. scouts and a large force of Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Lakota Sioux warriors in September 1868, the Beecher Island Battleground is today listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

• Manufactured in

1905, the Kit Carson Carousel is the only hand-carved carousel in the nation with full original paint and one of only sixteen National Historic Landmarks in Colorado.

• Present-day I-70 roughly follows the former Smoky Hill Trail. The Starvation Trail, a cutoff at Limon, gained this name after a party of fourteen men started from Kansas, but only one made it to Denver. Nine turned back; four died along the trail from lack of food and water. The sole traveler, found near Limon, survived by resorting to cannibalism.

• Housed in Hugo’s historic Hedlund House, the Lincoln County Museum features period furnishings and clothing. Highlights include a “lean-to” kitchen and an exhibit on President Theodore Roosevelt’s 1903 visit to Hugo.

• Comprising only 120 square feet, the smallest jailhouse in the United States can be seen in Haswell.

• Sand Creek Massacre (on private land). On November 29, 1864 the Third Regiment of Colorado Volunteers attacked an unsuspecting Cheyenne and Arapaho village at Sand Creek. Over 150 Indians—mostly women and children—were killed, bringing a new wave of conflict to Colorado’s high plains.

Erected 2001 by Colorado Historical Society, Colorado Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration.

Topics and series. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: Roads & Vehicles • Settlements & Settlers • Wars, US Indian. In addition, it is included in the Colorado - History Colorado, and the Rural Electrification 💡 series lists. A significant historical date for this entry is November 29, 1864.

Location. 39° 7.972′ N, 103° 27.878′ W. Marker is in Hugo, Colorado, in Lincoln County. Marker can be reached from 4th Street (U.S. 287) west of 7th Avenue, on the right when traveling west. Touch for map. Marker is in this post office area: Hugo CO 80821, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 4 other markers are within 15 miles of this marker, measured as the crow flies. Welcome to Lincoln County (a few steps from this marker); Hugo Municipal Pool (about 400 feet away, measured in a direct line); Lincoln County World War I Memorial (approx. 0.3 miles away); Arriba Country (approx. 14.6 miles away).

Credits. This page was last revised on August 19, 2017. It was originally submitted on August 19, 2017, by Duane Hall of Abilene, Texas. This page has been viewed 493 times since then and 36 times this year. Photos: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. submitted on August 19, 2017, by Duane Hall of Abilene, Texas.