Corvallis in Benton County, Oregon — The American West (Northwest)

River Transport

Corvallis quickly earned a reputation as a reliable upriver destination for Portland freight to be transferred to overland pack trains taking supplies south to the miners in southern Oregon and California. The activities of the hundreds of men and animals needed to move these commodities also earned Corvallis (then named “Marysville”) the reputation as a town of “freighters, saloon-keepers and gamblers.”

By 1852, steamboats carried tons of local grain and produce from Corvallis to Portland, destined for Hawaii, China, Japan and California. It was a profitable business ... The Canemah charged a healthy 20 cents per bushel to reansport wheat from Avery & Company's Corvallis warehouses to Portland.

Steamboats also were the primary passenger transportation for Corvallis. In 1854, the Canemah’s owner, the Citizens Accommodation Line, established a regular schedule between Corvallis and Oregon City five days a week. Passenger travel to Corvallis continued for the next 64 years, until the last regularly scheduled boat, operated by the Oregon City Transportation Company, left Corvallis on May 6, 1918.

Corvallis was considered the uppermost point of navigation until 1856, when the sternwheeler James Clinton became the first steamboat to travel upriver from Corvallis, reaching Eugene on March 12, 1856. It took three days of navigating the uncharted meandering river with its mud flats, sloughs, rocks, sunken logs and overhanging trees. After that trip, Eugene, Harrisburg and Peoria became regular upstream steamboat destinations during high water.

Initially, steamboats could reach Corvallis only nine months of the year when the river levels were high enough. Steamboat traffic to Corvallis and upriver became more reliable when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began regular channel-clearing work between Salem and Eugene starting in July of 1871.

Corvallis steamboat traffic got another boost with the opening of the canal and locks around Willamette Falls at Oregon City in 1873. Finally, a steamboat could travel from Portland upriver without transferring cargo around the falls.

Corvallis was subject to the changing rivalries, mergers and monopolies of the times. Early companies serving the upper Willamette included the Willamette Steam Navigation Company, which was absorbed by the People's Transportation Company, which was then absorbed by Ben Holladay’s Oregon Central Railway empire. The railroad companies controlled much of the steamer traffic in later years, including the Oregon Pacific Railroad and the Union Pacific’s Oregon Railway and Navigation Company.

There were occasional efforts to challenge the bog companies. Citizens in south Benton County formed the Long Tom Transportation Company and operated the steamer Ann, the first steamer to reach Monroe on February 17, 1869. That company folded two months later when the Ann sank near Harrisburg with a thousand bushels of wheat.

Corvallis founder Joseph Avery and local farmers formed the Willamette Navigation Company in 1870 to compete with the People’s Transportation Company. Avery’s group operated the 100-foot steamer Calliope, noted for reaching Lebanon on the Santiam in 1871.

The challenges of shallow water navigation generated some new approaches to steamer construction. Noteworthy was the Ohio built by U.B. Scott in 1873 for the upper river. Described as an ungainly flat-bottomed scow, the sternwheeler sat only 9" deep in the water, and drew only 18" of water loaded with 100 tons of freight. She occasionally would lose her paddle wheel in shallow water, but Scott’s boat was one of the few that could regularly reach Eugene, and reportedly made more than $10,000 in clear profit in her first three months of operation.

A Corvallis inventor created the strangest

craft on the upper Willamette, the cattle-powered vessel named “Hay Burner.” According to Howard McKinley Corning in his book, Willamette Landings:

Steam vessels had been plying the Willamette and Columbia rivers for fully a decade when, in 1860, a “genius” at Corvallis decided that they were too expensive to operate. So he rigged a scow with treadmill machinery, using cattle and hay for motive power. Coming downstream on its first trip, the vessel ran aground –or rather, walked ashore–at McGooglin’s Slough, where the boat remained until the cattle had devoured nearly all the fuel. It was finally pulled off by a steamer appropriately name Onward and then continued down the river to Canemah. But once there the Hay Burner lacked sufficient power to return to Corvallis against the current. The skipper sold his oxen and abandoned his enterprise.

(Inset):

Log Rafts

In 1889, the Corvallis Times reported that a million feet of pulp logs were passing Corvallis on their way to the paper mills at Oregon City, towed by steamers.

Though steamboating faded by the 1920s, log rafting continued. By 1947, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reported that rafted logs were the major item of commerce on the upper Willamette, above the falls at Oregon City.

Corvallis was a convenient upriver site for assembling log rafts. Logs were brought by truck to riverside “log dumps,” dropped into the river and cabled into rectangular “lockages”– rafts built to fit through the locks at Oregon City. At Corvallis, up to ten lockages were linked together to make a large raft over a quarter-mile long. The rafts were then moved downriver by tugboat.

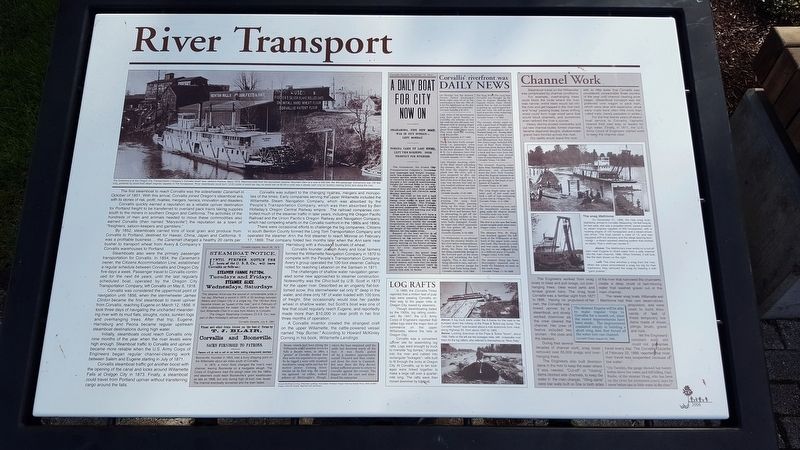

Channel Work

Steamboat travel on the Willamette was complicated by channel conditions.

For example, overhanging trees could block the route where the river was narrow; entire trees would fall into the river and get trapped in the river bed and “snag” passing boats; loose drifting wood could form huge wood jams that would block channels, and sometimes even redirect the river’s course.

Heavy storms eroded riverbanks and cut new channel routes; former channels became dead-end sloughs; shallow-water gravel bars formed across the river.

Dry spells would leave the river with so little water that Corvallis was considered unreachable three months of the year until channel clearing work began. (Steamboat transport was still preferred over wagon of pack train, which were slow and expensive, since early roads were often little more than rutted trails, barely passable in winter.)

For the first twenty years of steamboat service to Corvallis, captains cleared their own way, or waited for high water. Finally, in 1871, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers started work to keep the channel clear.

The snag Mathloma

On November 21, 1896, the new snag boat, Mathloma, arrived in Corvallis. Measuring 134 feet long by 34 feet wide, she was a propeller-driven vessel powered by steam engines capable of 400 horsepower, with a hoisting engine of 150 horsepower and a steam-driven pile driver. The boat carried a crew of 13, and was equipped with hot showers and the latest steering technology – a steam-assisted steering system that worked so easily “that a child can handle it.”

The Engineers worked from snag boats to blast and pull snags, cut overhanging trees, clear wood jams and scrape gravel bars. The snag boat Corvallis was a familiar sight from 1877 to 1896. Having no propulsion of her own, the Corvallis was towed upriver by a steamboat, and slowly worked downriver as the crew cleared the channel. Her crew of twelve included two women – the cook and the steward.

During their several decades of channel work, snag boats removed over 65,000 snags and overhanging trees.

The Engineers also built diversion dams in the river to keep the water where it was needed. “Cut-off” or “closing” dams blocked side channels, to keep the water in the main channel. “Wing dams” were low walls built on one or both sides of the river that narrowed the channel to create a deep chute of fast moving water that washed gravel out of the main channel.

The newer snag boats Willamette and Mathloma had their own steam-driven propulsion, and were used to build thousands of feet of these temporary low dams made of driven pilings, brush, gravel and rock.

Yet the Engineers’ constant work still could not guarantee travel every day. The Corvallis Gazette of February 22, 1889, reported that most river travel was suspended because of low water:

“On Tuesday, the gauge showed but twenty inches above low water, and still falling. Capt. Raabe, of the steamer Hoag, who has been on the river for seventeen years, says he never before saw so little water in the river.”

Erected 2004 by Madison Avenue Task Force.

Topics. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: Industry & Commerce • Waterways & Vessels. A significant historical month for this entry is October 1851.

Location. 44° 33.775′ N, 123° 15.542′ W. Marker is in Corvallis, Oregon, in Benton County. Marker is on SW 1st Street north of SW Jefferson Avenue, on the right when traveling north. Touch for map. Marker is in this post office area: Corvallis OR 97333, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. Early Town Development (here, next to this marker); Benton County State Bank (within shouting distance of this marker); L.G. Kline Building (about 500 feet away, measured in a direct line); City Hall (approx. 0.2 miles away); Capitol of Territorial Oregon (approx. 0.2 miles away); The Whiteside Theatre (approx. 0.2 miles away); The Opera House (approx. 0.2 miles away); Site of the Earliest Boat Landing (approx. 0.2 miles away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Corvallis.

Credits. This page was last revised on May 28, 2018. It was originally submitted on May 17, 2018, by Douglass Halvorsen of Klamath Falls, Oregon. This page has been viewed 231 times since then and 55 times this year. Photos: 1, 2, 3. submitted on May 18, 2018, by Douglass Halvorsen of Klamath Falls, Oregon. • Syd Whittle was the editor who published this page.