Near White Bird in Idaho County, Idaho — The American West (Mountains)

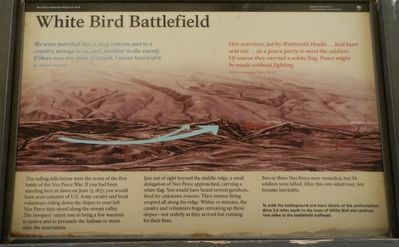

White Bird Battlefield

We were marched into a deep canyon and to a country strange to us, and familiar to the enemy. If there was any plan of attack, I never heard of it. -- Sgt. Michael McCarthy

“Five Warriors, led by Wettiwetti Houlis ... had been sent out ... as a peace party to meet the soldiers. Of course they carried a white flag. Peace might be made without fighting. -- himi-n maqsmáqs (Yellow Wolf)

The rolling hills below were the scene of the first battle of the Nez Perce War. If you had been standing here at dawn on June 17, 1877, you would have seen columns of U.S. Army cavalry and local volunteers riding down the slopes on your left. Nez Perce tipis stood along the stream valley. The troopers’ intent was to bring a few warriors to justice and to persuade the Indians to move onto the reservation.

Just out of sight beyond the middle ridge, a small delegation of Nez Perce approached, carrying a white flag. You would have heard several gunshots, fired for unknown reasons. Then intense firing erupted all along the ridge. Within 10 minutes, the cavalry and volunteers began retreating up these slopes -- not orderly as they arrived but running for their lives.

Two or three Nez Perce were wounded, but 34 soldiers were killed. After this one-sided rout, war became inevitable.

To walk the battleground and learn details of the confrontation, drive 3.4 miles south to the town of White Bird and continue two miles to the battlefield trailhead.

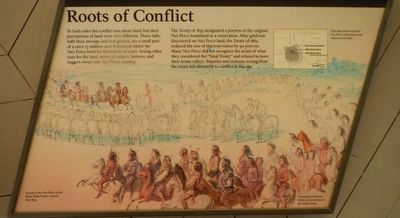

To both sides the conflict was about land, but their perceptions of land were very different. These hills, with their streams and rich grasses, are a small part of a once 17-million-acre homeland where the Nez Perce lived for thousands of years. Seeing other uses for the land, waves of miners, farmers, and loggers swept into Nez Perce country.

The Treaty of 1855 designated a portion of the original Nez Perce homeland as a reservation. After gold was discovered on Nez Perce land, the Treaty of 1863 reduced the size of the reservation by 90 percent. Many Nez Perce did not recognize the terms of what they considered the “Steal Treaty” and refused to leave their home valleys. Injustice and violence arising from the treaty led ultimately to conflict at this site.

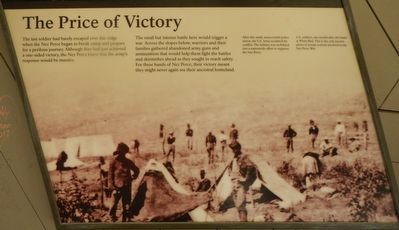

The last soldier had barely escaped over this ridge when the Nez Perce began to break camp and prepare for a perilous journey. Although they had just achieved a one-sided victory, the Nez Perce knew that the army’s

Photographed By Barry Swackhamer, May 5, 2018

2. Roots of Conflict panel

Captions: (upper right) This map shows how the Nez Perce reservation was reduced over time.; (bottom left) Arrival of the Nez Perce at the Walla Walla Treaty council, May 1855.; (bottom right) Drawing by Gustavus Sohon, an eyewitness to the treaty event.

The small but intense battle here would trigger a war. Across the slopes below, warriors and their families gathered abandoned army guns and ammunition that would help them fight the battles and skirmishes ahead as they sought to reach safety. For these bands of Nez Perce, their victory meant they might never again see their ancestral homeland.

After this small, unsuccessful police action, the U.S. Army escalated the conflict. The military was mobilized into a nationwide effort to suppress the New Perce.

Erected by National Park Service, Nez Perce National Historical Park.

Topics and series. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: Native Americans • Wars, US Indian. In addition, it is included in the The Nez Perce Trail series list. A significant historical date for this entry is June 17, 1877.

Location. 45° 48.115′ N, 116° 17.227′ W. Marker is near White Bird, Idaho, in Idaho County. Marker is on U.S. 95 near Trueblood Lane, on the right when traveling north. Touch for map. Marker is in this post office area: White Bird ID 83554, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within 12 miles of this marker, measured as the crow flies. Nez Perce War (here, next to this marker); Truce or War (approx. 1½ miles away); June 17, 1877 (approx. 1½ miles away); Salmon River

(approx. 3.6 miles away); White Bird Grade (approx. 3.7 miles away); Camas Prairie (approx. 5.8 miles away); Gathering at Tipahxlee’whum (Tepahlewam) (approx. 8.1 miles away); The ADVANCE Steam Traction Engine (approx. 11.7 miles away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in White Bird.

More about this marker. Three panels are located at this kiosk overlooking the White Bird Battlefield. This is one of the 38 sites that make up Nez Perce National Historical Park.

Also see . . . The Battle of White Bird Canyon: First Fight of the Nez Perce -- HistoryNet. The Battle of White Bird Canyon was a U.S. military fiasco that (Captain David) Perry (of the !st Cavalry) said was’scarcely exceeded by the magnitude of the Custer Massacre in proportion to the numbers engaged.’ On the Army side, 34 men had died; on the Indian side, nobody was killed and only three warriors were wounded. Perry, to his credit, had kept his troops from being annihilated, but unlike Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer, Perry had to live with his defeat and an Indian war that could have been prevented. (Submitted on August 5, 2018, by Barry Swackhamer of Brentwood, California.)

Credits. This page was last revised on August 5, 2018. It was originally submitted on August 5, 2018, by Barry Swackhamer of Brentwood, California. This page has been viewed 469 times since then and 57 times this year. Photos: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. submitted on August 5, 2018, by Barry Swackhamer of Brentwood, California.