The Mexican-American War

1846-1848

Fifteen years before Americans began fighting each other in the Civil War, they were at war with their neighbors to the south in Mexico. The Mexican-American War began in 1846 and lasted less than two years with the Americans achieving a sound victory. But as it turned out, it would also be a victory that would reignite the slavery debate throughout the country. In many ways, the Mexican-American war served as the launching point for the Civil War.

The United States went to war with Mexico in 1846 primarily for four reasons. First, Mexico was angry at the United States for annexing Texas in 1845. Since 1836, when Texas won its independence from Mexico in the Texas War of Independence, Mexico had refused to recognize it as an independent republic. Instead, Mexico saw Texas as a Mexican territory in rebellion. They warned the United States not to take it as their own, but when the U.S. finally did just that, Mexico broke off diplomatic relations with them on March 6, 1845. Second, Mexico and the United States could not agree on the exact boundary between Texas an Mexico. Mexico argued that the Nueces River was the true boundary while America believed it to be the Rio Grande River, a border that would give the U.S. much more territory. Third, Mexico had promised to pay off three million dollars that it owed

to the United States, but it kept defaulting on its payments. Finally, the United States' attempt to buy California from Mexico led to increased tension be- tween the two countries. In 1845, the President of the United States James Polk sent John Slidell to Mexico City to settle the Texas border dispute and offer them thirty million dollars for California and New Mexico. The Mexican government refused to receive Slidell or entertain his offer.Angry about what he perceived to be a slight to American honor, President Polk sent in troops to the disputed area between the Nueces and Rio Grande rivers. But this dispatch of troops was not entirely about hurt feelings. Polk was a firm believer in the concept of Manifest Destiny - the idea that the United States was destined to spread over the continent of North America, specifically westward to the Pacific Ocean. California was a key piece in the plan and if Mexico was unwilling to sell it, a military solution was another option.

Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to lead American troops to the Rio Grande River where Mexican forces were stationed, a move certain to provoke the Mexican army. On April 25, 1846, Mexican troops crossed the river killing or wounding sixteen American troops. Polk had already been preparing a war message to Congress before the Mexican attack based on Slidell's snub and Mexico's failure to pay its debts,

but now he had firmer grounds for war. On May 11, in a message delivered to Congress, Polk claimed that the United States had done all it could to avoid war with Mexico, but now the enemy had shed "American blood upon the American soil." Congress officially declared war on Mexico on May 13, 1846. The Mexican-American war had begun. Though Congress overwhelmingly voted for the war declaration, the U.S. was divided over the war especially along party lines. Polk's party, the Democrats, supported the conflict. But most Whigs, the other prominent political party of the time, thought the war was just a greedy land grab by President Polk. Antislavery factions in the country strongly opposed the war, seeing it as an attempt by southerners simply to create new slave states out of new territory gained in the war.When the war began, the U.S. military focused on two fronts. General Stephen Kearny would move west into northern Mexican territory, California and New Mexico, while General Zachary Taylor would lead troops south across the Rio Grande into central Mexico. Through 1846 and 1847, Kearny met little resistance. First, he led troops from Fort Leavenworth to Sante Fe which he managed to seize with very little effort. From there, Kearny began to move towards California to accomplish the second leg of his task, subduing California. But before he made it there, he learned that U.S. Captain

John Frémont and Commodore Robert Stockton had already captured the province. When Kearny finally made it to California at the end of 1846, he found that the U.S. had lost control of most of California to Californios, Mexican-Californians fighting independently without the support of Mexico. Kearny joined his forces with those of Frémont and Stockton to fight and win two decisive battles in the Los Angeles area against the Californios on January 8-9, 1847, the Battles of San Gabriel and La Mesa. With these two victories, the United States once again controlled California.Meanwhile, General Zachary Taylor crossed the Rio Grande winning some early battles relatively easily. However, at an important battle to seize the significant city of Monterrey, Taylor's forces met stiff resistance. Both sides suffered heavy losses, but in the end, Taylor and the Americans were able to secure a victory. The cost of victory was a weakened American force, but one that would ultimately win Taylor's greatest victory of the war at Buena Vista, The Battle of Buena Vista (February 23-24, 1847) pitted Taylor's force of about five thousand against Santa Anna's fifteen thousand Mexican troops. Taylor's troops were barely able to survive, but thanks to heavy U.S. artillery fire, the Mexicans were forced to retreat. Because Taylor was able to repel a force three times the size of his own, he became a hero throughout the United States immediately. This fame eventually propelled him to the presidency in 1848.

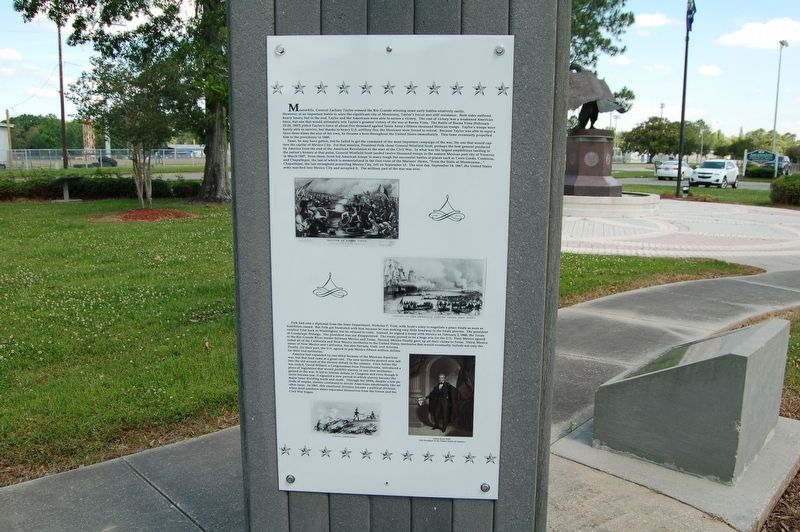

Fame, he may have gotten, but he failed to get the command of the most important campaign of the war, the one that would capture the capital of Mexico City. For that mission, President Polk chose General Winfield Scott, perhaps the best general produced by America from the end of the American Revolution to the start of the Civil War. In what was the largest amphibious landing in the nation's history at that point, General Winfield Scott landed twelve thousand troops in the eastern Mexican port city of Veracruz in March 1847. From there, Scott led American troops in many tough but successful battles at places such as Cerro Gordo, Contreras, and Chapultepec, the last of which is memorialized in the first verse of the Marines' Hymn, “From the Halls of Montezuma..." Chapultepec, the last stronghold protecting Mexico City, fell on September 13. The next day, September 14, 1847, the United States army marched into Mexico City and occupied it. The military part of the war was over.

Polk had sent a diplomat from the State Department, Nicholas P. Trist, with Scott's army to negotiate a peace treaty as soon as hostilities ceased. But Polk got frustrated with him because he was making very little headway in the treaty process. The president recalled Trist back to Washington, but he refused to come. Instead, he signed a treaty with Mexico on February 2, 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The president was not disappointed. The treaty proved to be a huge win for the U.S. First, Mexico agreed to the Rio Grande River border between Mexico and Texas. Second, Mexico finally gave up all their claims to Texas. Third, Mexico ceded all of the California and New Mexico territories to the United States, territories that would eventually include not only the states of New Mexico and California, but also Nevada, Utah, and Arizona. Finally, for their part, the U.S. agreed to pay Mexico fifteen million dollars for their lost territories.

America had expanded by one-third because of the Mexican-American war, but that land came at a great cost. The new territories poured new salt into the old wound of the slavery debate in the country. Even before the war ended, David Wilmot, a Congressman from Pennsylvania, introduced a piece of legislation that would prohibit slavery in any new territories gained in the war. It led to intense debate in Congress and even though it never became law, it signaled a new period in which slavery became the major issue dividing north and south. Through the 1850s, despite a few periods of respite, slavery continued to divide Americans emotionally like no other issue. In 1861, this emotional division became a political division, when most southern states separated themselves from the Union and the Civil War began.

Topics and series. This historical marker is listed in this topic list: War, Mexican-American. In addition, it is included in the Former U.S. Presidents: #11 James K. Polk, and the Former U.S. Presidents: #12 Zachary Taylor series lists.

Location. 30° 13.696′ N, 90° 54.804′ W. Marker is in Gonzales, Louisiana, in Ascension Parish. Marker can be reached from South Irma Boulevard, 0.3 miles north of East Worthey Street, on the right when traveling north. Touch for map. Marker is in this post office area: Gonzales LA 70737, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. Mexico Will Poison Us (here, next to this marker); a different marker also named The Mexican-American War (here, next to this marker); Star Spangled Banner (a few steps from this marker); The Battle of New Orleans, 1815 (a few steps from this marker); The War of 1812 (a few steps from this marker); The Freedom Fountain (a few steps from this marker); Civil War (within shouting distance of this marker); a different marker also named Civil War (within shouting distance of this marker). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Gonzales.

More about this marker. Located in the Gonzales Veterans Memorial Park

Credits. This page was last revised on April 25, 2021. It was originally submitted on March 10, 2018, by Cajun Scrambler of Assumption, Louisiana. This page has been viewed 637 times since then and 26 times this year. Photos: 1, 2, 3. submitted on March 10, 2018.