Greenville in Wayne County, Missouri — The American Midwest (Upper Plains)

Tie-Hacking

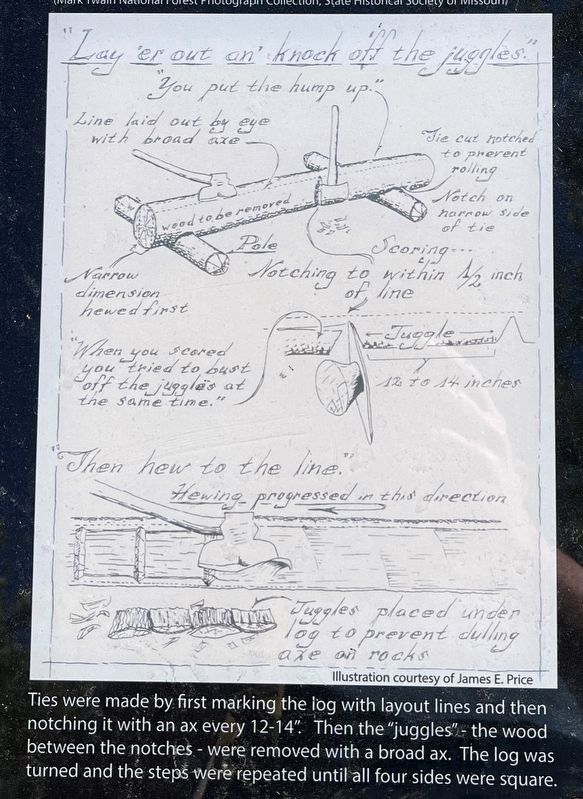

"Lay'er out an' Knock off the Juggles

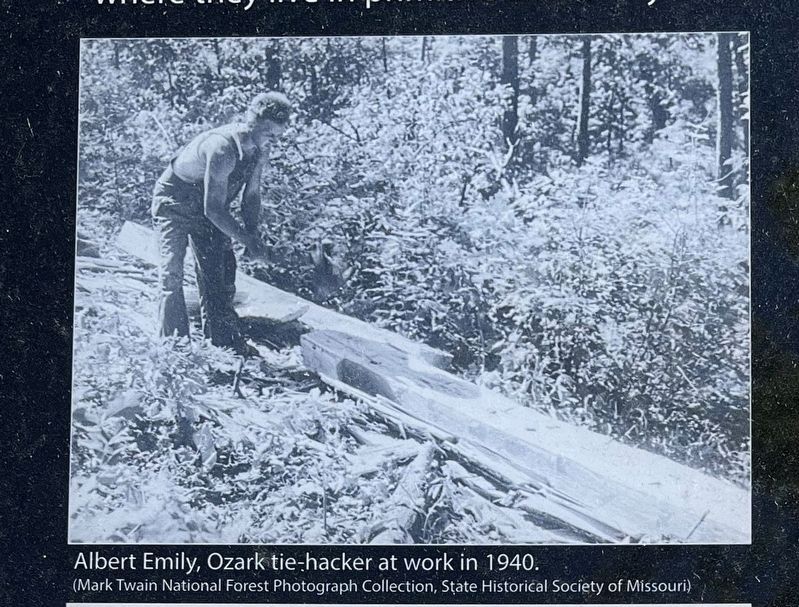

"These (men) work either in the employ of the tie contractors or independently. They usually build shacks in the forest, where they live in primitive and lonely fashion.

Tie hackers are looked down upon by the farming population and often are a somewhat lawless element. When the tie timber has been exhausted at one locality, they move to another, rarely remaining at one place more than a few years. They accumulate few possessions and develop slight social inclinations." Carl Sauer 1915

A century ago, hacking was way of life in the Ozarks. At that time, hacking didn't involve un authorized access to computer data, hacking was how railroad ties were made. Tie-hackers typically worked in two-man teams. hard working teams could hew about twenty hardwood railroad ties in an 11-hour workday, earning each man about a dollar.

The best trees for tie making were white or black oaks about a foot in diameter, with a trunk tall and straight enough to make at least two, eight-foot ties. Larger trees were used but required splitting the trunk. When a tie-hacker could make four ties from a section of tree trunk, they were called quarters ties. Half moon ties were made from section of trunk that was split in half. Bastard ties were made from trees so large that six or more ties could be split and hewed from a section of the trunk. Ties cut from smaller trees, those used to make just one tie by boxing out the heart of the tree, were called pole ties. Pole tie trees were preferred by many tie-hackers because they were the easiest to fin, fell and handle.

Trees were felled with a one or two-man cross-cut saw, sawed to length and split with wooden mauls and wedges if necessary, After marking the logs without lines, they were notched with an ax and then the "juggles' between the notches were hacked off with a broad ax. Cross-ties measured either 6 × 8 or 7 × 9 inches thick and were usually eight feet long. When green, oak ties weighed between 250 and 300 pounds.

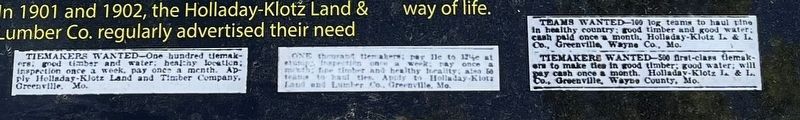

In 1901 and 1902, the Holladay-Klotz land & Lumber Co. regularly advertised their need for hundreds of tie-makers. Some men worked full time as tie hackers, but tie-hacking was also a way for Ozark farmers to earn much need cash during the winter.

In the early 1900s, tie-hackers were typically paid 10 cents per tie and 12 to 14 cents for longer switch ties. The Holladay-Klotz Land & Lumber Co.'s want ads in St. Louis newspapers promised pay "in cash" once a month, but in practice tie hackers typically needed advances against their earnings. Those advances were always paid in company script, coupons good for food and merchandise at the company stores.

Payment at the 'stump' was also somewhat misleading.

Hackers had to carry their ties, often over steep uneven terrain, to the nearest forest road accessible by mule-drawn wagon. A backwoods Ozark insult for a man who appeared unusually scrawny or weak was "that guy can't even carry a tie."

A single mile of railroad track is supported by 3000 cross-ties and untreated ties last just 4 to 6 years. In 1912, over 15 million hand hewed railroad ties were made by tie-hackers in the forest of southeastern Missouri. While demand remained great, by the early 1930s, the market had changed. White oak became more valuable for barrel staves than railroad ties, and tie-hackers shifted to making stave bolts. In the 1930s, creosote chemical treatment and portable sawmills that could saw ties at a cheaper price, with less waste, and from lower quality trees put an end to the Ozark tie-hacker's way of life.

Erected by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, St. Louis District.

Topics. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: Industry & Commerce • Railroads & Streetcars. A significant historical year for this entry is 1900.

Location. 37° 6.046′ N, 90° 27.4′ W. Marker is in Greenville, Missouri, in Wayne County. Marker can be reached from U.S. 67, 2 miles south of County Road 221, on the right when traveling south. Located on the "Memory Lane" trail

Photographed By Craig Swain, September 28, 2022

3. Tie Hacking - Knock Off the Juggles

Illustration on the lower left of the marker. Ties were made by first marking the log with layout lines and then notching it with an ax every 12-14". Then the "juggles" - the wood between the notches - were removed with a broad ax. The log was turned and the steps were repeated until all four sides were square.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. Sam Brown (here, next to this marker); Greenville Jailhouse (within shouting distance of this marker); The Wayne County Courthouse At Old Greenville (within shouting distance of this marker); Harry S. Truman (within shouting distance of this marker); She Poisoned His Tomato Wine (within shouting distance of this marker); Wayne County Courthouse (within shouting distance of this marker); Keep Right! (within shouting distance of this marker); Ward's Store (within shouting distance of this marker). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Greenville.

Additional commentary.

1. Spelling on the marker

The use of script has been taken verbatim from the marker, as opposed to the accurate term scrip. The use of company scrip was made illegal in the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

— Submitted December 4, 2021, by Devry Becker Jones of Washington, District of Columbia.

Photographed By Craig Swain, September 28, 2022

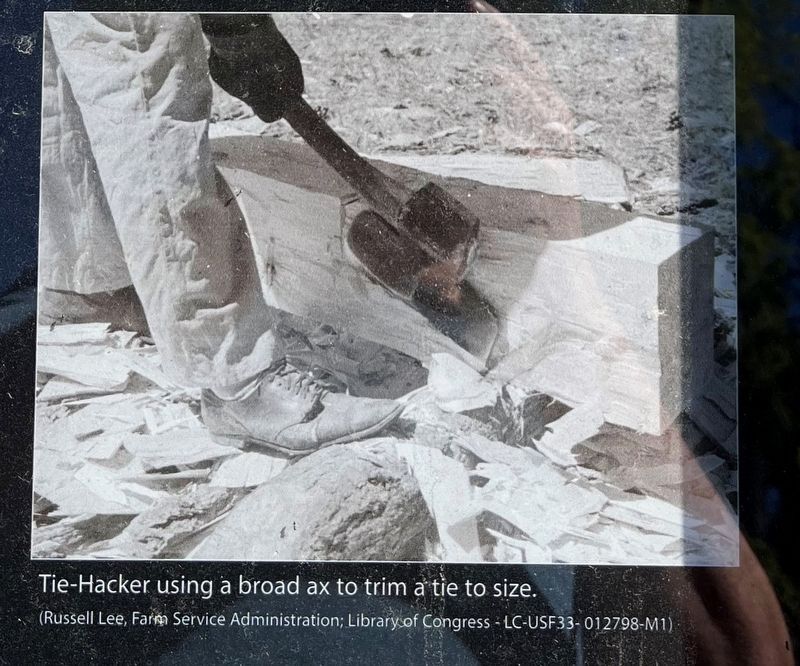

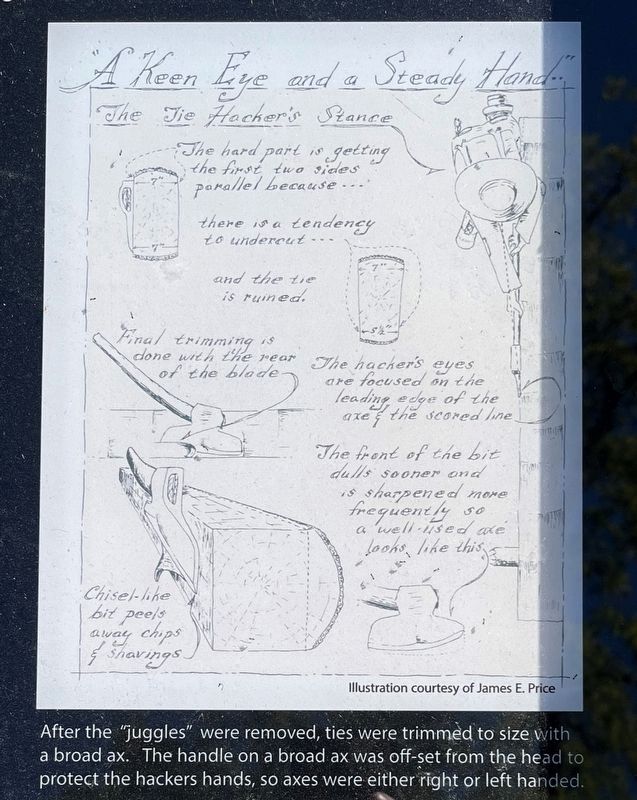

4. Trimming the Tie to Size

Illustration on the upper right, courtesy of James E. Price.

After the "juggles" were removed, ties were trimmed to size with a broad ax. The handle on a broad ax was off-set from the head to protect the hackers hands, so axes were either right or left handed.

After the "juggles" were removed, ties were trimmed to size with a broad ax. The handle on a broad ax was off-set from the head to protect the hackers hands, so axes were either right or left handed.

Credits. This page was last revised on November 7, 2022. It was originally submitted on December 4, 2021, by Thomas Smith of Waterloo, Ill. This page has been viewed 495 times since then and 56 times this year. Photos: 1. submitted on December 4, 2021, by Thomas Smith of Waterloo, Ill. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. submitted on November 7, 2022, by Craig Swain of Leesburg, Virginia. • Devry Becker Jones was the editor who published this page.