Spartanburg in Spartanburg County, South Carolina — The American South (South Atlantic)

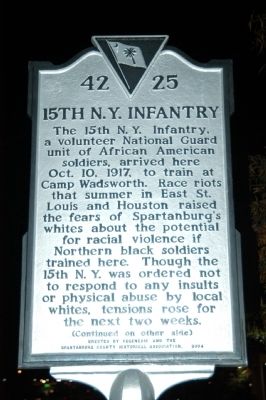

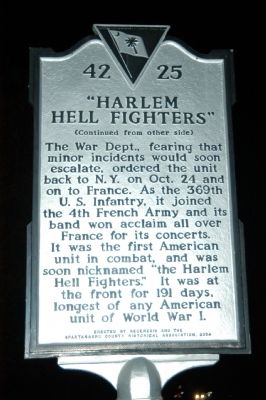

15th N.Y. Infantry / Harlem Hell Fighters

Inscription.

Erected 2004 by Spartanburg County Historical Association. (Marker Number 42-25.)

Topics. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: African Americans • War, World I. A significant historical year for this entry is 1917.

Location. 34° 56.178′ N, 81° 59.442′ W. Marker is in Spartanburg, South Carolina, in Spartanburg County. Marker is at the intersection of W. O. Ezell Boulevard (U.S. 29) and East Blackstock Road (South Carolina Highway 295), on the right when traveling east on W. O. Ezell Boulevard. Touch for map. Marker is in this post office area: Spartanburg SC 29301, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within 3 miles of this marker, measured as the crow flies. Colonel Warren H. Abernathy Highway (about 500 feet away, measured in a direct line); John B. White Sr., Blvd. (approx. one mile away); Camp Wadsworth (approx. 1.2 miles away); Harold Hatcher (approx. 1.9 miles away); Berlin Wall (approx. 2.4 miles away); Dr. Jesse F. Cleveland Junior High School (approx. 2.8 miles away); Spartanburg Methodist College (approx. 2.9 miles away); "Sparky" the Family Train (approx. 3.1 miles away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Spartanburg.

Also see . . .

1. Scott's Official History of the American Negro in the World War. This site is the source of some of the pictures on this page. (Submitted on November 10, 2008, by Michael Sean Nix of Spartanburg, South Carolina.)

2. 369th Infantry Regiment "Harlem Hellfighters". (Submitted on November 10, 2008, by Michael Sean Nix of Spartanburg, South Carolina.)

3. 369th U.S. Infantry Regiment. The 369th Infantry Regiment, formerly the 15th New York National Guard Regiment, was nicknamed the Harlem Hellfighters and the Black Rattlers, in

addition to several other nicknames. (Submitted on April 28, 2011, by Brian Scott of Anderson, South Carolina.)

Additional commentary.

1. 15th N.Y. Infantry/ 369th Infantry

While the Great War raged in Europe for three long years, America steadfastly clung to neutrality. It was not until April 2, 1917, that President Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany. "The world," he said, "must be made safe for democracy." Quickly, Americans swung into action to raise, equip, and ship the American Expeditionary Force to the trenches of Europe. Under the powers granted to it by the U.S. Constitution (Article I, Section 8) "to raise and support Armies," Congress passed the Selective Service Act of 1917. Among the first regiments to arrive in France, and among the most highly decorated when it returned, was the 369th Infantry (formerly the 15th Regiment New York Guard), more gallantly known as the "Harlem Hellfighters." The 369th was an all-black regiment under the command of mostly white officers including their commander, Colonel William Hayward.

Participation in the war effort was problematic for African Americans. While America was on a crusade to make the world safe for democracy abroad, it was neglecting the fight for equality at home. Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) established that the 14th Amendment allowed for separate but equal treatment under the law. In 1913 President Wilson, in a bow to Southern pressure, even ordered the segregation of federal office workers. The U.S. Army at this time drafted both black and white men, but they served in segregated units. After the black community organized protests, the Army finally agreed to train African American officers but it never put them in command of white troops.

Leaders of the African American community differed in their responses to this crisis. A. Philip Randolph was pessimistic about what the war would mean for black Americans -- he pointed out that Negroes had sacrificed their blood on the battlefields of every American war since the Revolution, but it still had not brought them full citizenship. W.E.B. DuBois argued that "while the war lasts [we should] forget our special grievances and close our ranks shoulder to shoulder with our white fellow citizens and allied nations that are fighting for democracy." And in full force, America's black population "closed ranks."

During World War I 380,000 African Americans served in the wartime Army. Approximately 200,000 of these were sent to Europe. More than half of those sent abroad were assigned to labor and stevedore battalions, but they performed essential duties nonetheless, building roads,

bridges, and trenches in support of the front-line battles. Roughly 42,000 saw combat.

American troops arrived in Europe at a crucial moment in the war. Russia had just signed an armistice with Germany in December 1917 freeing Germany to concentrate her troops on the Western Front. If Germany could stage a huge offensive before Americans came to the aid of her war-weary allies, Germany could win the war.

The 369th Infantry helped to repel the German offensive and to launch a counteroffensive. General John J. Pershing assigned the 369th to the 16th Division ofthe French Army. With the French, the Harlem Hellfighters fought at Chateau-Thierry and Belleau Wood. All told they spent 191 days in combat, longer than any other American unit in the war. "My men never retire, they go forward or they die," said Colonel Hayward. Indeed, the 369th was the first Allied unit to reach the Rhine.

The extraordinary valor of the 369th earned them fame in Europe and America. Newspapers headlined the feats of Corporal Henry Johnson and Private Needham Roberts. In May 1918 they were defending an isolated lookout post on the Western Front, when they were attacked by a German unit. Though wounded, they refused to surrender, fighting on with whatever weapons were at hand. They were the first Americans awarded the Croix de Guerre, and they were not the only Harlem Hellfighters

to win awards; 171 of its officers and men received individual medals and the unit received a Croix de Guerre for taking Sechault.

(Source from the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration Webpage)

— Submitted November 9, 2008, by Michael Sean Nix of Spartanburg, South Carolina.

Credits. This page was last revised on June 16, 2016. It was originally submitted on November 9, 2008, by Michael Sean Nix of Spartanburg, South Carolina. This page has been viewed 3,776 times since then and 51 times this year. Last updated on July 29, 2009, by Richard E. Miller of Oxon Hill, Maryland. Photos: 1, 2. submitted on November 9, 2008, by Michael Sean Nix of Spartanburg, South Carolina. 3. submitted on April 28, 2011, by Brian Scott of Anderson, South Carolina. 4, 5. submitted on July 12, 2009, by Stanley and Terrie Howard of Greer, South Carolina. 6, 7, 8. submitted on November 9, 2008, by Michael Sean Nix of Spartanburg, South Carolina. • Kevin W. was the editor who published this page.