The Legend Of John Henry

The Ballad of John Henry

When John Henry was a little baby

No higher than his daddy's knee,

He picked up a hammer and a little piece of steel

Saying, "Hammer's gonna to be the death of me, Lord, Lord,

Hammer's gonna be the death of me."When John Henry came up to the mountain

He stopped and rested on the side;

Said, "This mountain's so tall and John Henry's so small,"

And he laid down his hammers and he cried, "Lord, Lord,"

Laid down his hammers and he cried.John Henry said to the captain,

Said, "I'm a steel-drivin' man.

"I want double pay 'cause I work a double day

"With a four-foot hammer in each hand, Lord, Lord,

"A four-foot hammer in each hand."Well, each day they drove steel in the mountain,

Falling rock would strike down two or three.

He said, "This Big Bend Tunnel on the C & O Road,

"Gonna be the death of me, Lord, Lord,

"Gonna be the death of me."The captain said to John Henry,

"I think the mountain's cavin' in."

John Henry just laughed and never missed a stroke,

Said, "Nothing but my hammers suckin' wind, Lord, Lord,

"Nothin' but my hammers suckin' wind."Well, the captain said to John Henry,

steam drill down,

"You may be a steel-drivin' man,

"But if you can beat this ol'

"I'll lay a hundred dollars in your hand, Lord, Lord,

"Lay a hundred dollars in your hand."And John Henry said to the captain,

"A man ain't nothin' but a man,

"But before I let that steam drill beat me down,

"Ill die with my hammers in my hand, Lord, Lord,

"Die with my hammers in my hand."Well, they put John Henry on the right side;

The steam drill was on the left.

Said, "Before I let that steam drill beat me down.

"I'll hammer my fool self to death, Lord, Lord,

"Hammer my fool self to death."John Henry said to his shaker,

"Little Bill, you better pray,

"For if I miss the six-foot steel,

"Gonna be your buryin' day, Lord, Lord,

"Gonna be your buryin' day."With his hammers flashing in the mountain,

John Henry started to sing:

"Can't you drive her, hunh, can't you drive her, hunh;

"Just listen to that cold steel ring, Lord, Lord,

"Listen to that cold steel ring."Well, the man who invented that ol' steam drill,

Thought it was mighty fine,

But John Henry drove his steel down fourteen feet

And the steam drill only made nine, Lord, Lord,

The steam drill only made nine.John Henry laughed at the steam drill,

drive steel like me, Lord, Lord,

For he'd won for all to see.

Said, "Your hole's done choke and your drill's done broke

"And you can't

"You can't drive steel like me."Then John Henry said to the captain,

"I got an awful roarin' in my head,

"I beat down that steam drill but I busted my insides;

"Tomorrow John Henry will be dead, Lord, Lord,

"Tomorrow John Henry will be dead."Well, they buried John Henry at the portal,

His hammers in his hands,

And every locomotive that comes rollin' through

Shakes the bones of a steel-drivin' man, Lord, Lord,

Shakes the bones of a steel-drivin' man.*This version of the ballad was compiled by Hank Burchard, Washington writer and John Henry buff. First published in the Washington Post in 1969.

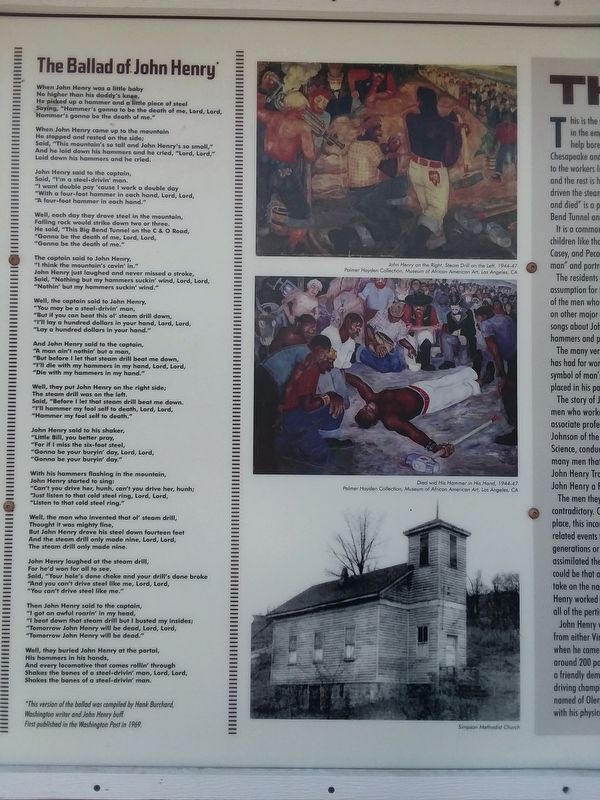

This is the site where the Legend of John Henry was born. A steel driver in the employment of Captain William R. Johnson, he was employed to help bore the Great Bend Tunnel through Big Bend Mountain for the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway. When a steam drill showed up at the site, a threat to the workers livelihood became evident. John Henry challenged it to a contest and the rest is history, Most accounts agree that after about an hour he had out driven the steam drill by more than five feet. He then "laid down his hammer and died” is a point of contention. However, John Henry did work in the Great Bend Tunnel and this has been substantiated by historians.

It is a common misconception that the story of John Henry is a tall tale for children like those about his fellow American folk heroes Paul Bunyan, Mighty Casey, and Pecos Bill, In some stories he is mistakenly thought to be a "railroad man” and portrayed as a gandy dancer driving spikes into rail ties.

The residents of Talcott and the surrounding area will disagree with this assumption for they know the true account of the legend. So do the descendants of the men who made up the construction gangs that built railroads and worked on other major construction projects. These were the men who made up work songs about John Henry's exploits and chanted them in time to the blows of their hammers and picks.

The many versions of the work songs that are sung show the appeal his story has had for working men and women over the years. John Henry has become a symbol of man's determination to overcome natural and man-made obstacles placed in his path and increasing advancements in technology.

The story of John Henry the man was developed from the accounts of the men who worked alongside him at the tunnel. Dr. Louis W. Chappell, an associate professor of English at West Virginia University, and Dr. Guy B. Johnson of the University of North Carolina Institute for Research in Social Science, conducted extensive interviews during the mid

to late 1920's with many men that had knowledge of the affair. In 1928, Dr. Johnson published John Henry Tracking Down a Negro Legend. In 1933, Dr. Chappell published John Henry a Folklore Study.The men they interviewed provided testimonies that were at times contradictory. Considering that 50 years had gone by since the contest had taken place, this inconsistency could have been due to the fact that most of interviewees related events that had been passed down to them though the preceding generations or from stories and songs. However, when the information was assimilated the results found that it supported an actual event. Another reason could be that after the Civil War it was not uncommon for newly freed men to take on the name John Henry. Therefore, it is probable that more than one John Henry worked on the tunnel. Unfortunately, a fire at the C&0'S offices destroyed all of the pertinent contractor's records and reports.

John Henry was an African American possibly newly freed from enslavement from either Virginia or North Carolina. He was between 30 and 35 years old when he came to the tunnel in 1870. He stood about six feet tall and weighed around 200 pounds with muscles tempered from a life of hard work. He had a friendly demeanor and was a popular man at the site. He was also the steel driving champion of the camp (possibly having beaten a

fellow steel driver by the named of Olery or 0'Leary for that title). His proficiency as a steel driver along with his physical endurance earned him the respect of the entire camp. Some of the ballads place a women coming to him during the night without fear of being molested due to his reputation. Other accounts state that he had a wife by the name of Pollie Ann. This supports the local belief that Pollie Ann is buried in the Simpson Methodist Church Cemetery (the cemetery is all that remains) near Pie Hollow.John Henry was in charge of his work gang where he set the pace singing in time with his blows. One man who had been a water boy on his shift remembered him as "the singin' est man I ever saw.” John Henry would not even break rhythm to call for water but would chant in a booming voice without missing a stroke;

Ain't I getting' dry, hunh

A swinging this hammah, hunh

Songs were sung to help the workers maintain an even workable pace throughout the day. The songs also served to keep their minds off of the dangerous dreary conditions that they labored under. Most of the songs were lively tunes about fellow workers, loose women, bosses, and heroes like John Henry or anything else that caught their fancy. The setting of the story of his celebrated contest with the steam drill was acted out in a wild and colorful setting one befitting

a great legend. An observer during that period described the Countryside around Big Bend Mountain as "a howling wilderness".Workers, whose job it was to drill the horizontal holes into the heading of the tunnel and into the unlined roof on occasions, were constantly in danger of rock falls. John Henry excelled in this environment. He and his fellow steel drivers performed their work by their will and strength drilling holes in the rock for black powder charges or an explosive called Dualin. As many as 50 holes, sometimes up to 14 feet deep, were required for each shot. When the rock was blown free, it was mucked out by hand and hauled away in mule drawn carts.

It is often said that John Henry used two hammers (it is the general consensus that the hammers were smaller than standard size) and was the only driver who could manage this feat. Swinging one after another in each hand, few shakers could keep up with such a pace. Phil Henderson or Little Bill as some of the ballads refer to him was John Henry's trusted shaker. This trust worked both ways as one stanza of several ballads purport.

John Henry told his shaker,

"Shaker, you bette' pray

For if I miss this six-foot steel

Tomorrow 'll be your burial day, Lawd Lawd!

Tomorrow 'll be your burial day"

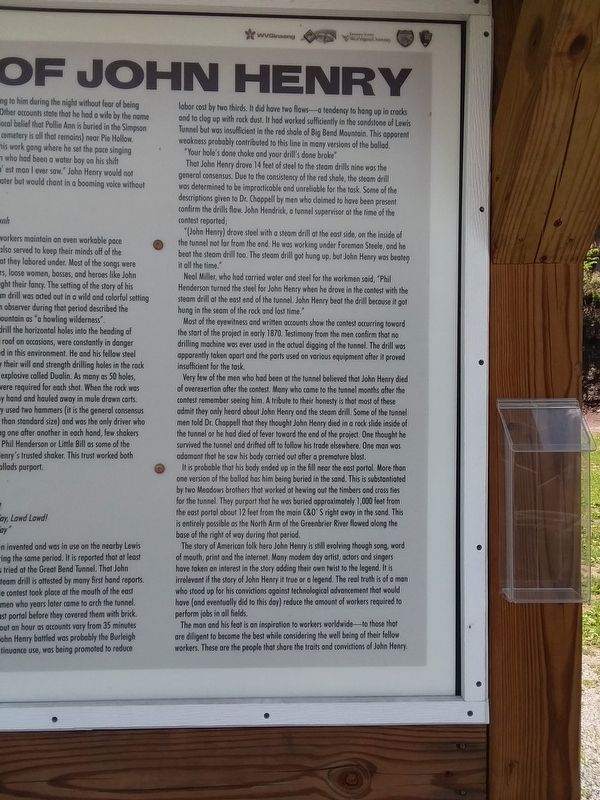

The steam power drill had been invented and was in use on the nearby

Lewis Tunnel also built by the C&0 during the same period. It is reported that at least one model of the steam drill was tried at the Great Bend Tunnel. That John Henry challenged and beat the steam drill is attested by many first hand reports. All of the witnesses agree that the contest took place at the mouth of the east portal. This is also supported by men who years later came to arch the tunnel. They saw the drill holes in the east portal before they covered them with brick.The contest probably lasted about an hour as accounts vary from 35 minutes to two hours. The machine that John Henry battled was probably the Burleigh stream drill. The machine, in continuance use, was being promoted to reduce labor cost by two thirds. It did have two flaws-a tendency to hang up in cracks and to clog up with rock dust. It had worked sufficiently in the sandstone of Lewis Tunnel but was insufficient in the red shale of Big Bend Mountain. This apparent weakness probably contributed to this line in many versions of the ballad.

"Your hole's done choke and your drill's done broke"

That John Henry drove 14 feet of steel to the steam drills nine was the general consensus. Due to the consistency of the red shale, the steam drill was determined to be impracticable and unreliable for the task. Some of the descriptions given to Dr. Chappell by men who claimed to have been present confirm the drills flaw. John Hendrick, a tunnel supervisor at the time of the contest reported;

"(John Henry) drove steel with a steam drill at the east side, on the inside of the tunnel not far from the end. He was working under Foreman Steele, and he beat the steam drill too. The steam drill got hung up, but John Henry was beaten it all the time."

Neal Miller, who had carried water and steel for the workmen said, "Phil Henderson turned the steel for John Henry when he drove in the contest with the steam drill at the east end of the tunnel. John Henry beat the drill because it got hung in the seam of the rock and lost time."

Most of the eyewitness and written accounts show the contest occurring toward the start of the project in early 1870. Testimony from the men confirm that no drilling machine was ever used in the actual digging of the tunnel. The drill was apparently taken apart and the parts used on various equipment after it proved insufficient for the task.

Very few of the men who had been at the tunnel believed that John Henry died of overexertion after the contest. Many who came to the tunnel months after the contest remember seeing him. A tribute to their honesty is that most of these admit they only heard about John Henry and the steam drill. Some of the tunnel men told Dr. Chappell that they thought John Henry died in a rock slide inside of the tunnel or he had died of fever toward the end of the project. One thought he survived the tunnel and drifted off to follow his trade elsewhere. One man was adamant that he saw his body carried out after a premature blast.

It is probable that his body ended up in the fill near the east portal. More than one version of the ballad has him being buried in the sand. This is substantiated by two Meadows brothers that worked at hewing out the timbers and cross ties for the tunnel. They purport that he was buried approximately 1,000 feet from the east portal about 12 feet from the main C&0' S right away in the sand. This is entirely possible as the North Arm of the Greenbrier River flowed along the base of the right of way during that period.

The story of American folk hero John Henry is still evolving though song, word of mouth, print and the internet. Many modem day artist, actors and singers have taken an interest in the story adding their own twist to the legend. It is irrelevant if the story of John Henry it true or a legend. The real truth is of a man who stood up for his convictions against technological advancement that would have (and eventually did to this day) reduce the amount of workers required to perform jobs in all fields.

The man and his feat is an inspiration to workers worldwide-to those that

are diligent to become the best while considering the well being of their fellow

workers. These are the people that share the traits and convictions of John Henry.

Topics. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: African Americans • Arts, Letters, Music • Railroads & Streetcars. A significant historical year for this entry is 1969.

Location. 37° 38.974′ N, 80° 46.02′ W. Marker is in Talcott, West Virginia, in Summers County. Marker is on West Virginia Route 3/12, 0.2 miles north of Huston Road, on the right when traveling east. On the grounds of the John Henry Historical Park. Touch for map. Marker is at or near this postal address: 243 State Hwy 3, Talcott WV 24981, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. Concrete & Cut Stone Foundations (here, next to this marker); John Henry (a few steps from this marker); John Henry In Fiction (within shouting distance of this marker); Great Bend Tunnel Construction (within shouting distance of this marker); Tunnel Construction Technology Improves (within shouting distance of this marker); Great Bend Tunnel (about 300 feet away, measured in a direct line); Why The Tunnel Was Built (about 300 feet away); a different marker also named Great Bend Tunnel (about 300 feet away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Talcott.

Credits. This page was last revised on December 3, 2022. It was originally submitted on January 20, 2021, by Craig Doda of Napoleon, Ohio. This page has been viewed 385 times since then and 66 times this year. Photos: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. submitted on January 20, 2021, by Craig Doda of Napoleon, Ohio. 6. submitted on November 22, 2022, by Tom Bosse of Jefferson City, Tennessee. • Devry Becker Jones was the editor who published this page.