Douglas (Bronzeville) in Chicago in Cook County, Illinois — The American Midwest (Great Lakes)

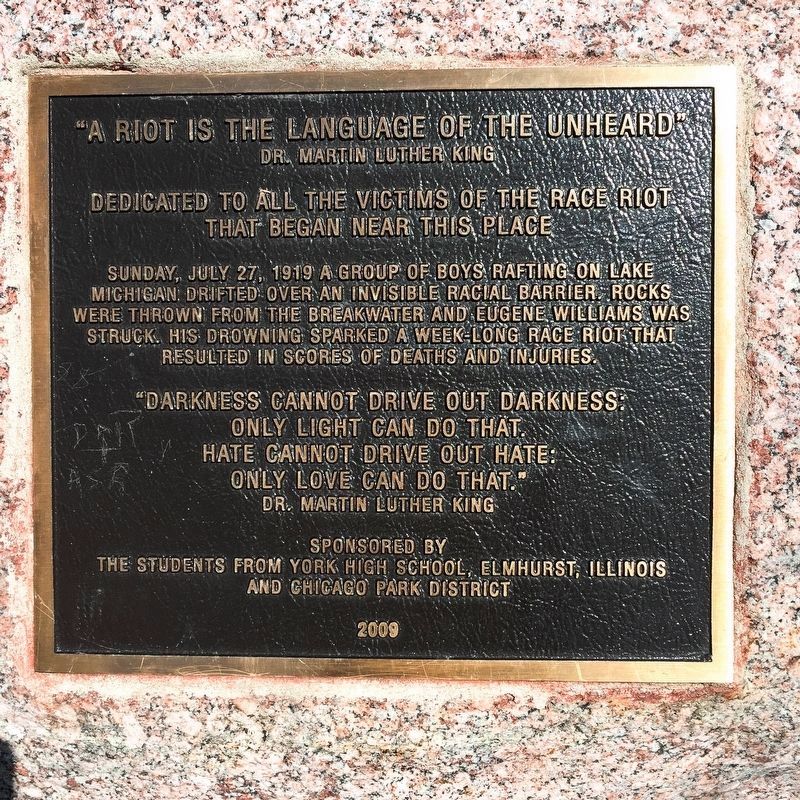

Eugene Williams Memorial

Dedicated to All the Victims of the Race Riot That Began Near This Place

“A riot is the language of the unheard.”

—Dr. Martin Luther King

Sunday, July 27, 1919, a group of boys rafting on Lake Michigan drifted over an invisible racial barrier. Rocks were thrown from the breakwater and Eugene Williams was struck. His drowning sparked a week long race riot that resulted in scores of deaths and injuries.

“Darkness cannot drive out darkness: only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate: only love can do that.”

—Dr. Martin Luther King.

Erected 2009 by the students from York High School, Elmhurst, Illinois, and Chicago Park District.

Topics. This historical marker and memorial is listed in these topic lists: African Americans • Disasters. A significant historical date for this entry is July 27, 1919.

Location. 41° 50.55′ N, 87° 36.535′ W. Marker is in Chicago, Illinois, in Cook County. It is in Douglas (Bronzeville). Marker is on Fort Dearborn Drive just north of East 31st Street, on the right when traveling north. Touch for map. Marker is at or near this postal address: 1125 Fort Dearborn Dr, Chicago IL 60616, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. Douglas Plaza (approx. 0.7 miles away); Camp Douglas (approx. 0.7 miles away); Stephen A. Douglas Memorial (approx. ¾ mile away); Stephen A. Douglas: The Douglas Tomb (approx. ¾ mile away); Stephen A. Douglas: Douglas and Lincoln (approx. ¾ mile away); Stephen A. Douglas: The Chicago Years (approx. ¾ mile away); Unity Hall (approx. ¾ mile away); Stephen Arnold Douglas (approx. ¾ mile away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Chicago.

Also see . . .

1. The Chicago Race Riot of 1919: How the Death of Eugene Williams shook America. 2020 article by Claire Barrett on HistoryNet.com.

Excerpt:

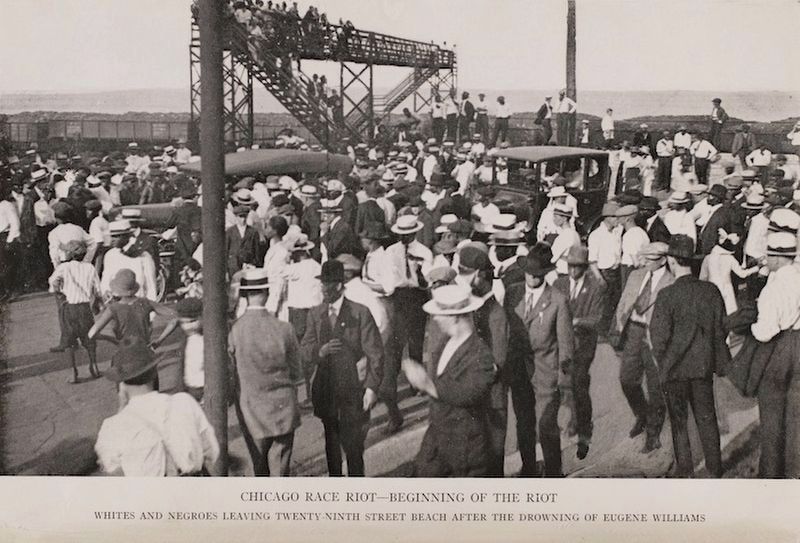

In July of that year, thousands of Chicagoans, amid the throes of a heatwave, thronged along the beaches of Lake Michigan. 29th Street beach was designated for whites and the 25th Street beach for blacks. This boundary even extended into the waters of Lake Michigan. On Sunday, July 27, Eugene Williams, a 17-year-old black youth, accidentally drifted into an area of water that was deemed to be for “whites only.”(Submitted on February 8, 2021.)

One white beachgoer, indignant, began hurling rocks at Williams, causing the teen to drown. The pervading rumor was that Williams was struck in the head by one of the stones and drowned. Although in the autopsy, Williams’ body showed no bruises. The official coroner’s report cited that Williams drowned because the stone throwing kept him from coming to shore.

On the beach, “guilt was immediately placed upon a certain white man by several Negro witnesses who demanded that he be arrested by a white policeman who was on the spot,” the study wrote. “No arrest was made.”

Tensions on the beach escalated and a skirmish ensued when the officer arrested a black man instead. “The riot was under way,” the study noted. Williams’ death was the spark that touched off nearly a week of active, violent protests. But it was just the spark. Deeply rooted factors and injustices within the city kindled the flame.

2. Red Summer In Chicago: 100 Years After The Race Riots. 2019 article by Karen Grisby Bates and Jason Fuller at NPR.org. Excerpt:

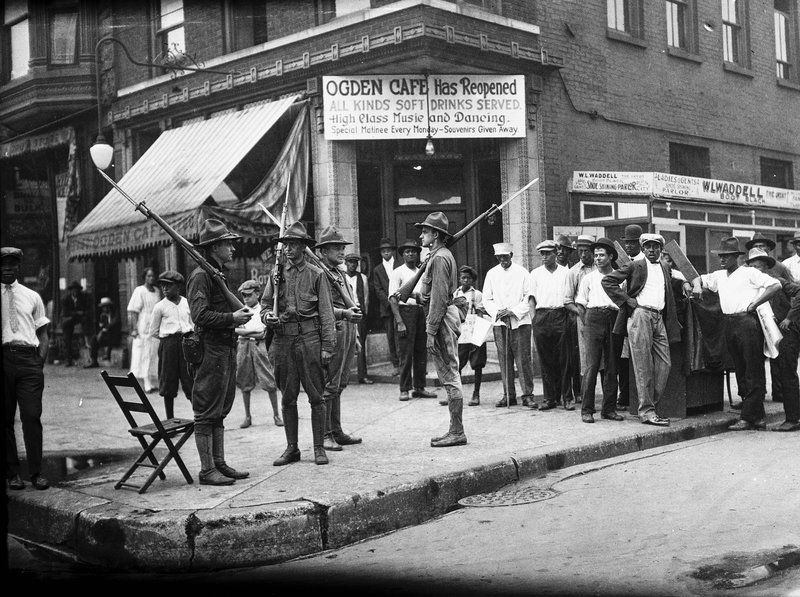

Her uncle was armed “with the biggest gun I had ever seen,” [Juanita] Mitchell [age 107] recalls. He was prepared to protect his family. So were many of the returning black veterans. A group of National Guard reserve men who’d returned from France after fighting valiantly there, broke into an armory and grabbed guns and other weapons, determined to protect black lives and property.(Submitted on February 8, 2021.)

That resistance was a watershed, says Timuel Black Jr. “I understand that this was the first time these Northern Negroes fought back from an attack and been successful.”

So successful, in fact, that the riot soon wound down.

“From what I’ve been told by my family who was here, the riotwas soon over, because the Westside rioters felt they were in danger, now that these Negroes returning from the war had weapons equal to their weapons.”

When the smoke cleared and the ashes cooled, 38 people—23 black, 15 white—were dead. More than 350 people reported injuries.

Credits. This page was last revised on November 2, 2023. It was originally submitted on February 8, 2021, by J. J. Prats of Powell, Ohio. This page has been viewed 721 times since then and 110 times this year. Photos: 1, 2, 3, 4. submitted on February 8, 2021, by J. J. Prats of Powell, Ohio.