Central Park West Historic District in Manhattan in New York County, New York — The American Northeast (Mid-Atlantic)

Seneca Village Landscape

Historical accounts portrayed those living in Seneca Village and the entire area slated for Central Park in derogatory terms. They also disparaged the landscape, empathizing it as rocky, swampy, and diseased. Park promoters presented the site as a wasteland to justify taking so much land for a recreational purpose, and to empathize the creation of the park as an extraordinary transformation. Closer study reveals the sections of the landscape were indeed swampy and rocky, but its acreage also contained small gardens, woodlands, and hills that some characterized as beautiful and productive.

Uncovering the history of Seneca Village has involved a closer examination of the landscape and its natural and built features. Researchers have tried to imaging how residents lived on the land and also discern what still remains of the mid-19th-century pre-park landscape. This process has illuminated Seneca Village as a place shaped by the actions and agency of residents as well as by the forces of urban growth and change.

Seneca Village and Urban Growth

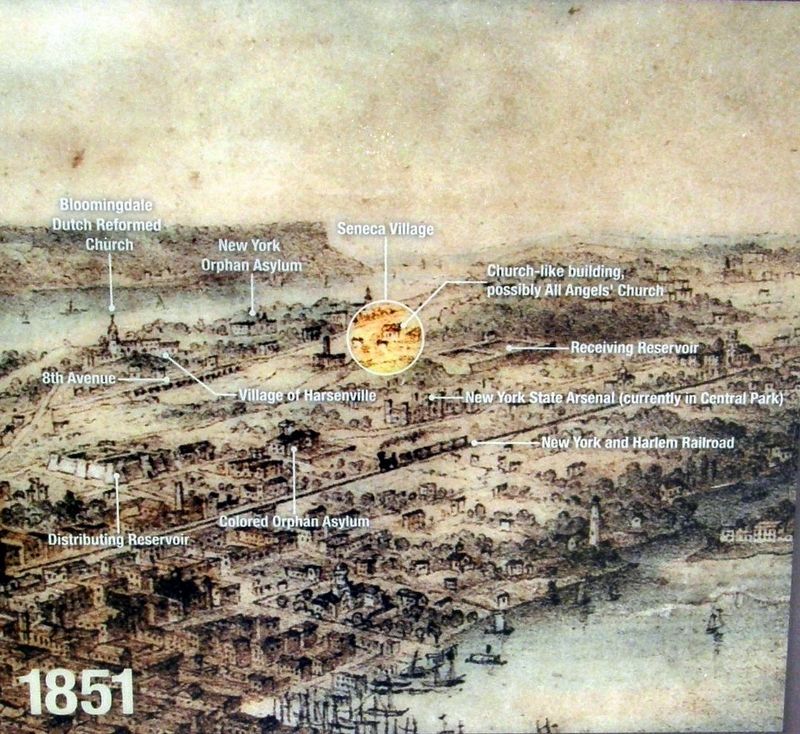

When the first African Americans began buying property in the area in 1825, the northern border of the city was around 23rd Street; by the time Seneca Village residents were forced to leave in 1857, the city was built up as far north as 50th Street. During this period, the city’s population increased almost sevenfold. Seneca Village was originally a remote settlement that researchers believe was viewed by its residents as a refuge from the crowded conditions and racist climate of Lower Manhattan. But even before Seneca Village was demolished, it became less remote. It was gradually encroached upon by forces of urbanization, forces that did not make much accommodation for African Americans or the poor.

Signs of the city’s relentless expansion and march northward were apparent in Seneca Village in its layout according to the grid plan and manifested over time through the construction of new streets such as Eighth Avenue and 86th Street, both in use by 1830. The reservoir was another prominent sign of urban growth. Completed in 1842, this huge structure was built to hold the city’s water supply and became a boundary of the east side of the village. Just before the park was initiated, the village was forced to adjust to another urban pressure. In 1851, when the city outlawed burials below 86th Street and prohibited establishment of any new burial grounds in Manhattan, the village’s churches had to acquire space in the newly-developed rural cemeteries in Queens.

Seneca Village and Central Park

The dramatic urban growth that impacted Seneca Village also spurred the city to create Central Park. City leaders conceived of a large park to counteract the detrimental effects of urban life – overcrowding, disastrous impacts on public health, and lack of open space for recreation. Some park supporters and businessmen also hoped that a park in the sparsely settled section of Manhattan would stimulate real estate development in the surrounding area.

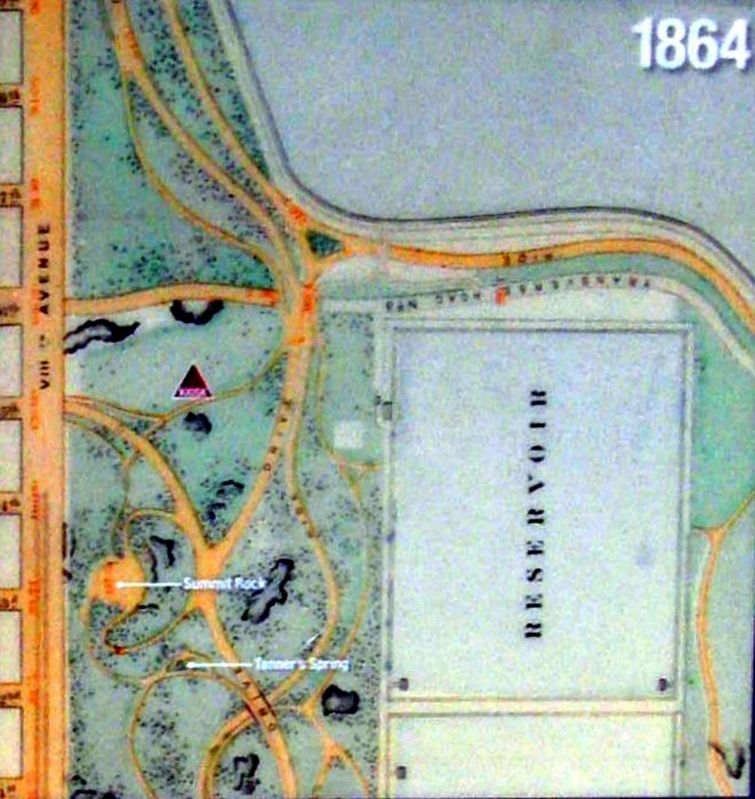

The construction of Central Park seemingly erased all traces of Seneca Village – residents were forced to move, houses were leveled, and the site was graded and landscaped. Even so, the site did not experience the total refashioning that produced iconic landscapes such as the Mall or Sheep Meadow. The presence of the reservoir and the hilly and rocky topography made radical transformation too challenging. The original design for the site consisted largely of paths and roads and the construction of a new reservoir to the north of the pre-existing one. In the 1930s, the Parks Department added the two playgrounds north and southwest of this sign and filed the original reservoir to create the Great Lawn.

Natural Features

Although it appears that all traces of Seneca Village were lost when the city built Central Park, some natural features do remain. Most prominent are the numerous outcrops throughout the site. The constraints of the geology of the Seneca Village area likely contributed to park designers Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux’s

decision to preserve some of the area’s character and existing features. These features also contributed to the designers’ ideal of scenic beauty and the park’s purpose as an escape from the city.

The Seneca Village site contains some of the area’s most impressive landforms including a massive outcrop now known as Summit Rock, the highest point in the park. This rock, virtually impossible for the park builders to remove, is a defining feature of the area and would have been quite prominent in the landscape of Seneca Village. Nearby is a natural spring, called Tanner’s Spring, believed to have been a principal water source for the village.

Erected 2020 by Central Park Conservancy.

Topics. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: African Americans • Parks & Recreational Areas • Settlements & Settlers. A significant historical year for this entry is 1825.

Location. 40° 47.05′ N, 73° 58.109′ W. Marker is in Manhattan, New York, in New York County. It is in the Central Park West Historic District. Marker can be reached from West 85th Street east of Central Park West. Touch for map. Marker is at or near this postal address: Central Park, New York NY 10024, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. Seneca Village Community (here, next to this marker); Searching for Seneca Village (a few steps from this

marker); Seneca Village (a few steps from this marker); The Wilson House (a few steps from this marker); African Union Church (within shouting distance of this marker); Gardens (within shouting distance of this marker); All Angels’ Church (within shouting distance of this marker); AME Zion Church (within shouting distance of this marker). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Manhattan.

Also see . . .

1. Seneca Village. Wikipedia entry (Submitted on April 18, 2021, by Larry Gertner of New York, New York.)

2. Seneca Village Site. Central Park Conservancy website entry:

Links to several related sub-topics (Submitted on April 18, 2021, by Larry Gertner of New York, New York.)

3. Seneca Village, New York City. National Park Service entry (Submitted on April 18, 2021, by Larry Gertner of New York, New York.)

Credits. This page was last revised on January 31, 2023. It was originally submitted on April 18, 2021, by Larry Gertner of New York, New York. This page has been viewed 146 times since then and 23 times this year. Photos: 1, 2, 3, 4. submitted on April 18, 2021, by Larry Gertner of New York, New York.