Ketchikan in Ketchikan Gateway Borough, Alaska — Northwest (North America)

Stedman-Thomas Historic District

The other downtown

Inscription.

Across the great divide: Stedman started apart

Ketchikan Creek formed a dividing line in Ketchikan in the early 1900s. To the north, white pioneers' homes, schools and churches stair-stepped up the hill and businesses crowded the waterfront. But south across the creek, a boardwalk landed in an ethnic, social and architectural medley — Stedman and Thomas streets. The first Stedman was a raised wooden walkway built in 1900. Buildings along the street rested on pilings and tides rose and fell below them. De facto segregation made it “Indian Town” and most of Ketchikan's Native residents settled here. In 1903, the City Council banished brothels to “the other side of the creek.” As industries grew, Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, Filipinos and Hispanics commingled with Alaska Natives along Stedman. A few Europeans and African-Americans also joined the small-world settlement.

That multicultural character led to inclusion of the neighborhood on the National Register of Historic Places in the 1990s. Some historical structures had disappeared, but preservation and renovation on Stedman kept the face of the old street fresh a century after its start.

Early in the district's growth, “proper folks” didn't tarry on Stedman: they passed through, legend has it, only to go to the cemetery, the canneries or a beach three miles south. But denizens of Stedman Street outlasted the tar brush. The harbor at Thomas Street drove an economic surge starting in the 1930s. Stedman Streeters built groceries and restaurants, hardware stores and pool halls, bars and marine-supply houses. By mid-century, Stedman was almost a city unto itself — vital, polyglot, easygoing.

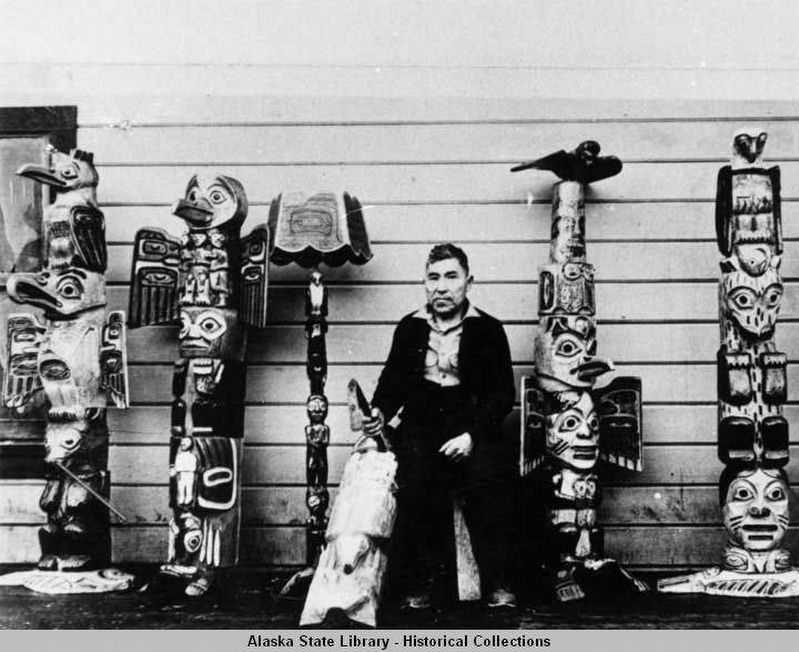

Natives sank roots in Indian Town

Southeast Alaska Natives were first to settle at the mouth of Ketchikan Creek, where a summer salmon camp had long been in use. White settlers established a salmon saltery and trading post there. Early in the 1900s, Natives from outlying islands moved to fast-growing Ketchikan to find work. Seafood processing was an occupational mainstay and Indian Town south of the creek was home.

Alaskeros Filipino-Alaskans flourished here

Visits began with the early explorers

Touch and go was the rule for Filipinos in Alaska for about a century and a half. Sailors from the Philippines visited Alaska as crewmen on Spanish and Russian ships as far back as the 1780s. In the early 20th century, hundreds of Filipinos worked each summer in Alaska's massive salmon industry, but these self-named Alaskeros left for home at season's end. Few Filipinos settled in Alaska until the conquest of their nation by Japan during World War II. By 1950, Ketchikan was home for most Filipino-Alaskans.

Workers

from the Philippines stepped into the shoes of Chinese and Japanese laborers, who worked Alaska mines and salmon processing lines until national exclusionary laws reduced their numbers. At the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898, the Philippines was ceded to the United States and Filipinos became U.S. nationals.

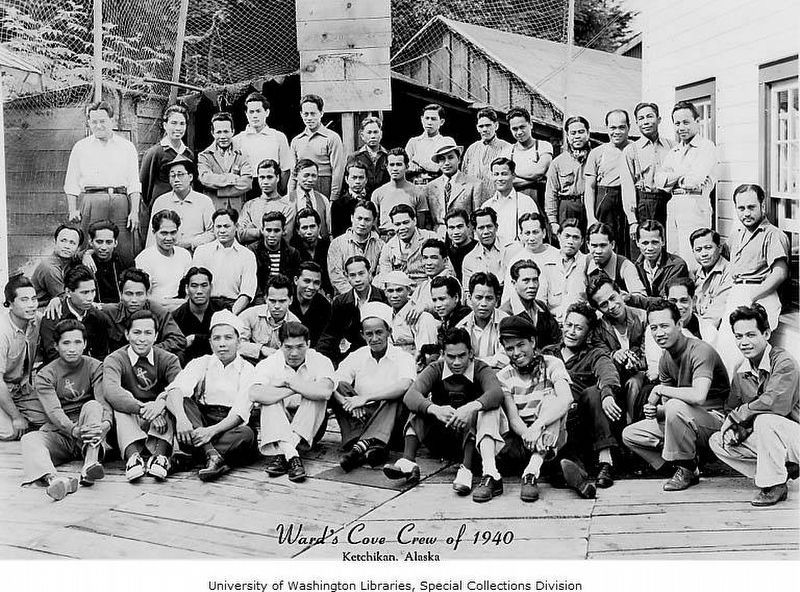

Trade in human labor developed in scores of canneries along the coast from the 1910s to the late 1930s. Contractors shipped hundreds of Filipinos to Alaska, principally from San Francisco and Seattle. Filipino cannery workers worked as much as 15 hours a day during salmon harvests.

Stedman Street was home for most of the Filipino men who stayed in Ketchikan. Many married Alaska Native women and settled down as sawmill workers, store owners, fishermen and laborers. The 1920 territorial census found fewer than 100 Filipino-Alaskans. The '40 census counted 400 Filipinos in Alaska — about half in Ketchikan; 80 percent were men. Alaska's Filipino population doubled each decade after the 1950s and was greater than 8,000 in the early 1990s.

A people apart on the Last Frontier

First-generation Filipinos in Alaska faced racial discrimination. Cannery workers of Asian heritage had inferior bunkhouses and food. In town, Filipinos were effectively segregated in housing, concentrating in so-called Indian Town south of the creek. At the

cinema and in the gym, Filipinos and Alaska Natives were set apart. In 1933, first- and second-generation Filipino-Americans founded the Filipino Social Club of Ketchikan. That group was succeeded by two other Filipino social organizations. The clubs provided outlets for people excluded from most entertainment businesses and social organizations.

Labor troubles here

Activists in Seattle and along the coast organized a cannery workers union in the mid-1930s, demanding higher wages and better working conditions. In 1936, Alaskeros earned about $65 a month on the cannery line. Filipinos were on both sides of the labor dispute: some of the labor contractors manipulating hiring and wages were Filipino-Americans. Strikes, jailings and animosity blazed on the coast from California to western Alaska until the union was certified in Seattle as Local 7 of United Cannery Workers and levered better pay and working conditions.

Captions

(Left side, top to bottom)

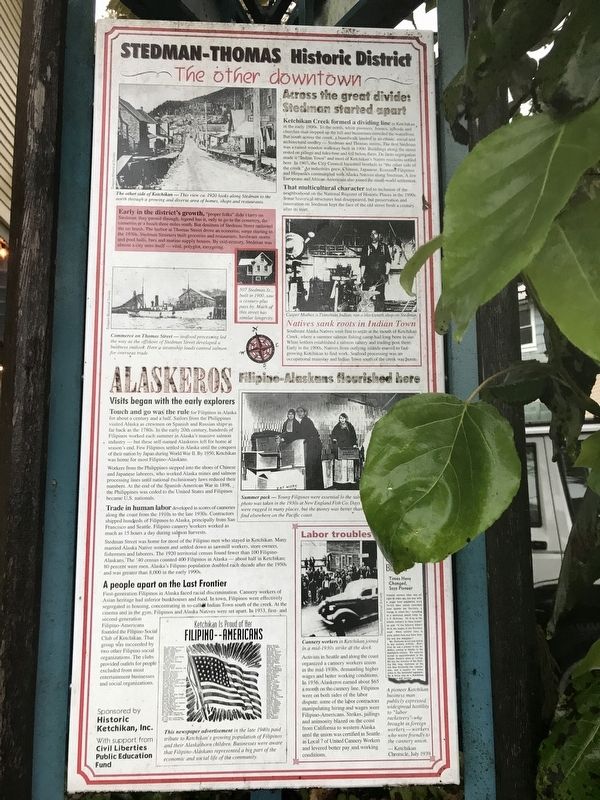

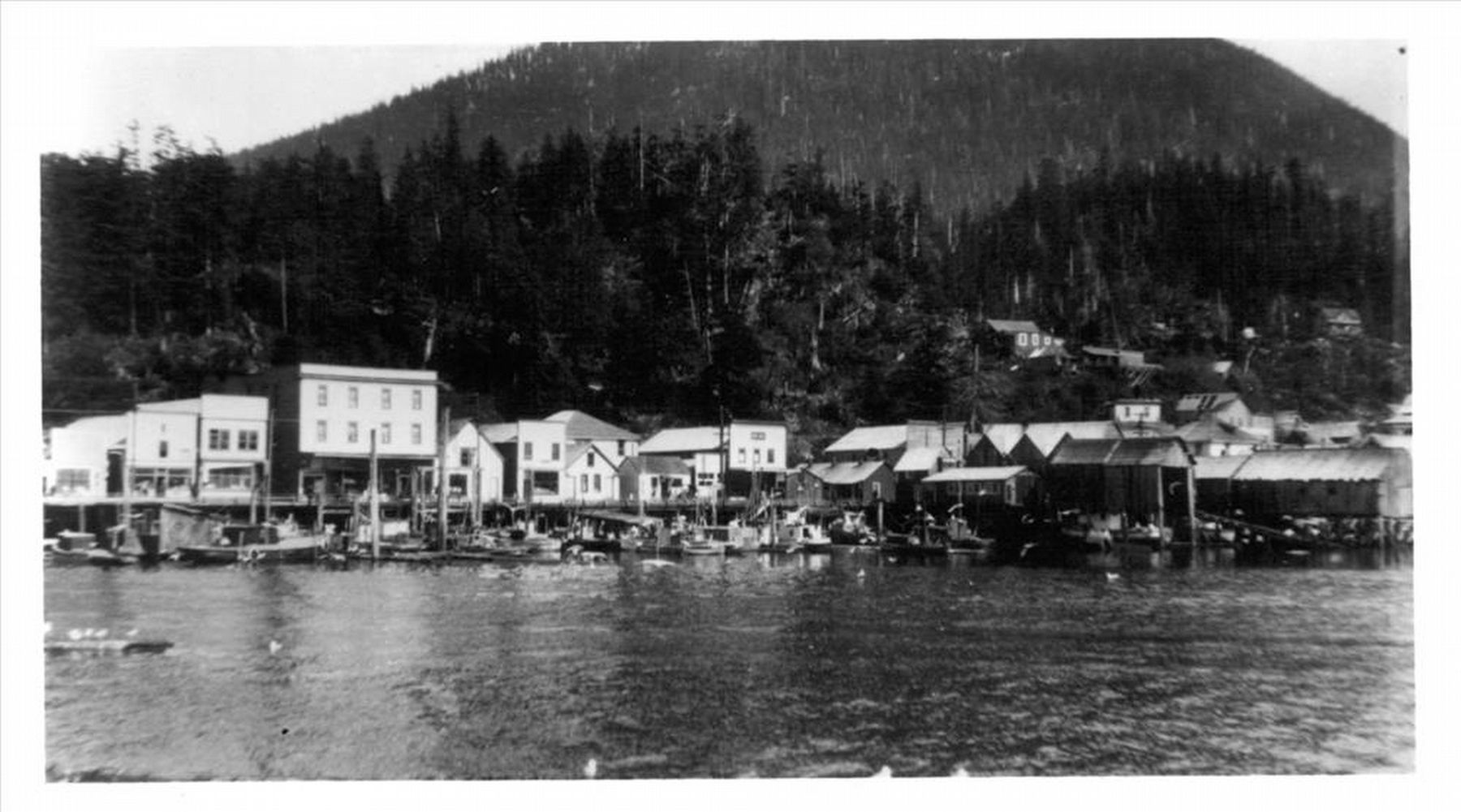

• The other side of Ketchikan — This view ca. 1920 looks along Stedman to the north through a growing and diverse area of homes, shops and restaurants. Tongass Historical Society

• 507 Stedman S., built in 1900, saw a century-plus pass by. Much of this street has similar longevity.

• Commerce on Thomas Street — seafood processing led the way as the

Photographed By Larry Gertner

4. Stedman-Thomas Historic District

National Register of Historic Places: Digital Archive on NPGallery website entry

Click for more information.

Click for more information.

• This newspaper advertisement in the late 1940s paid tribute to Ketchikan's growing population of Filipinos and their Alaska born children. Businesses were aware that Filipino-Alaskans represented a big part of the economic and social life of the community.

(Right side, top to bottom)

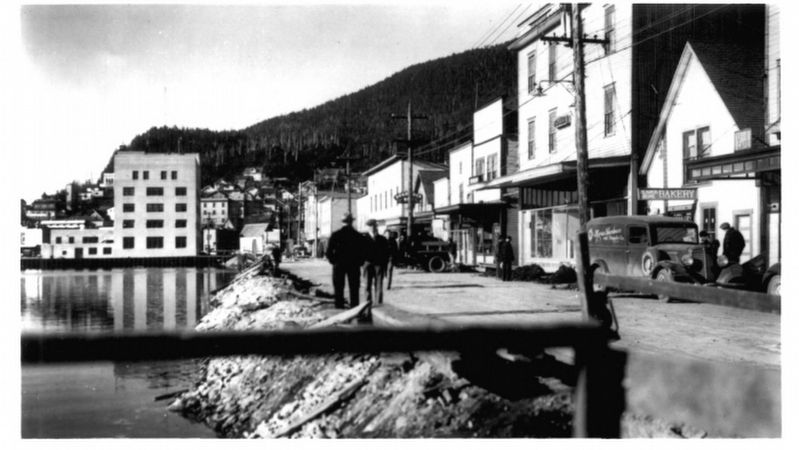

• Casper Mather, a Tsimshian Indian, ran a blacksmith shop on Stedman. Tongass Historical Society

• Summer pack — Young Filipinos were essential to the salmon canning industry when this photo was taken in the 1930s at New England Fish Co. Days were long and living conditions were rugged in many places, but the money was better than most unskilled workers could find elsewhere on the Pacific coast. Tongass Historical Society

• Cannery workers in Ketchikan joined in a mid-1930s strike at the dock. Tongass Historical Society

• A pioneer Ketchikan business man publicly expressed widespread hostility to “labor racketeers” who brought in foreign workers — workers who were friendly to the cannery union. — Ketchikan Chronicle, July 1939 Sponsored by Historic Ketchikan, Inc. With support from Civil Liberties Public Education Fund

Erected by Historic Ketchikan, Inc. • Civil Liberties Public Education Fund.

Topics. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: Asian Americans • Fraternal or Sororal Organizations • Industry & Commerce • Labor Unions.

Location. 55° 20.461′ N, 131° 38.443′ W. Marker is in Ketchikan, Alaska, in Ketchikan Gateway Borough. Marker is on Stedman Street south of Creek Street, on the left when traveling south. Touch for map. Marker is at or near this postal address: 207 Stedman Street, Ketchikan AK 99901, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. The Lost Frontier (here, next to this marker); New York Hotel & Café (here, next to this marker); Ohashi's (a few steps from this marker); June's Café (within shouting distance of this marker); Creek Street (within shouting distance of this marker); Dolly's House (within shouting distance of this marker); Diaz Café (about 300 feet away, measured in a direct line); 20 Creek Street (about 300 feet away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Ketchikan.

Also see . . . Filipinos in Alaska. Wikipedia entry (Submitted on September 17, 2021, by Duane and Tracy Marsteller of Murfreesboro, Tennessee.)

Credits. This page was last revised on September 18, 2021. It was originally submitted on September 17, 2021, by Duane and Tracy Marsteller of Murfreesboro, Tennessee. This page has been viewed 314 times since then and 52 times this year. Photos: 1, 2, 3. submitted on September 17, 2021, by Duane and Tracy Marsteller of Murfreesboro, Tennessee. 4. submitted on September 18, 2021, by Larry Gertner of New York, New York. 5, 6. submitted on September 17, 2021, by Duane and Tracy Marsteller of Murfreesboro, Tennessee.