Historic District - North in Savannah in Chatham County, Georgia — The American South (South Atlantic)

Savannah and the Slave Trade

Although slavery was illegal when the colony of Georgia was founded, it was a well established institution in other American colonies. Settlers were confronted with the economics to compete with slave labor. Carolinians produced cash crops with slave labor that significantly undersold commodities produced in Georgia by freedmen. South Carolina planters provided the first slaves that arrived in Georgia. Other Georgia settlers soon requested permission to own slaves. By 1748, some 350 slaves worked in Georgia, but officials took no action against their owners who violated the law. In 1750, Georgia Trustees resisted the legalization of slavery, but economic pressure forced a reversal of policy.

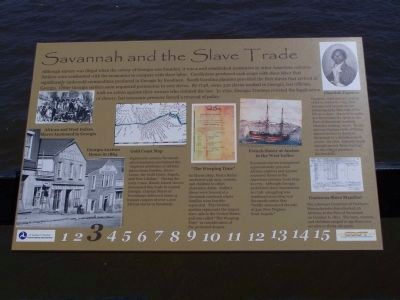

African and West Indian Slaves Auctioned in Georgia

Georgia Auction House in 1864

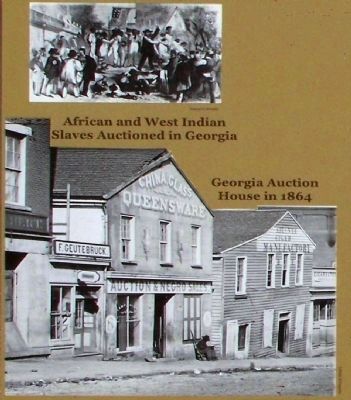

Gold Coast Map

Eighteenth-century Savannah advertisements proclaimed the "superior attributes of African slaves from Gambia, Sierra Leone, the Gold Coast, Angola, and New Calabar." During the early 1790s, Rhode Island slavers dominated this trade in Coastal Georgia. Cyprian Sterry of Providence delivered some 13 human cargoes of over 1,200 African slaves to Savannah.

"The Weeping Time"

In March 1859, Pierce Butler auctioned 436 men, women, and children to offset plantation debts. Butler's slaves were housed at a Savannah racetrack where families were forcibly separated. This historic auction represents the largest sale in the United States, and was called "The Weeping Time" in consideration of the profound despair.

French Slaver at Anchor in the West Indians

European slavers transported approximately 300,000 African captives and 25,000 seasoned slaves to the American colonies from 1619 to 1775. Although Georgia prohibited slave importation in 1798, smuggling was condoned according to a Savannah notice that "boldly announced the sale of 330 New Negroes fom Angola."

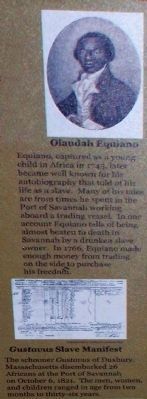

Olaudah Equiano

Equiano, captured as a young child in Africa in 1745, later became well known for his autobiography that told of his life as a slave. Many of his tales are from times he spent in the Port of Savannah working aboard a trading vessel. In one account Equiano tells of being almost beaten to death in Savannah by a drunken slave owner. In 1766, Equiano made enough money from trading on the side to purchase his freedom.

Gustavus Slave Manifest

The schooner Gustavus of Duxbury, Massachusetts disembarked 26 Africans at the Port of Savannah on October 6, 1821. The men, woman, and children ranged in age from two months to thirty-six years.

Erected 2009 by U.S. Dept. of Transportation Federal Highway Administration, Georgia Dept. of Transportation. (Marker Number 3.)

Topics. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: African Americans • Colonial Era • Industry & Commerce • Settlements & Settlers. A significant historical month for this entry is March 1859.

Location. 32° 4.91′ N, 81° 5.462′ W. Marker is in Savannah, Georgia, in Chatham County. It is in the Historic District - North. Marker is on East River Street, on the left when traveling east. Between Drayton Street Ramp & Abercorn Ramp, riverside. Touch for map. Marker is in this post office area: Savannah GA 31401, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. African American Monument (a few steps from this marker); Savannah Waterfront (a few steps from this marker); Jewish Colonists (within shouting distance of this marker); Savannah in the American Revolution (within shouting distance of this marker); Gen. Oglethorpe's Landing (within shouting distance of this marker); A Storeroom By Any Other Name (about 300 feet away, measured in a direct line); This is Yamacraw Bluff (about 300 feet away); Landing of Oglethorpe and the Colonists (about 300 feet away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Savannah.

Related markers. Click here for a list of markers that are related to this marker.

Also see . . . Olaudah Equiano at Wikipedia. Some suggest Equiano may have fabricated his African roots and survival of the Middle Passage to sell more copies of his book and advance the movement against the slave trade. Baptismal records and a naval muster roll linking Equiano to South Carolina have been found. Others counter that it is quite common for such discrepancies to exist in records of that era. (Submitted on June 3, 2009, by Mike Stroud of Bluffton, South Carolina.)

Photographed By Mike Stroud, January 1, 2008

5. The nearby African American Monument

We were stolen, sold and bought together from the African Continent

We got on the slave ships together, we lay back to belly in the holds of the

slave ships in each others excrement and urine together. Sometimes died

together and our lifeless bodies thrown overboard together. Today we are

standing up together with faith and even some joy.

-Maya Angelou

Credits. This page was last revised on February 8, 2023. It was originally submitted on June 3, 2009, by Mike Stroud of Bluffton, South Carolina. This page has been viewed 10,833 times since then and 219 times this year. Photos: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. submitted on June 3, 2009, by Mike Stroud of Bluffton, South Carolina. • Christopher Busta-Peck was the editor who published this page.