Downtown East in Minneapolis in Hennepin County, Minnesota — The American Midwest (Upper Plains)

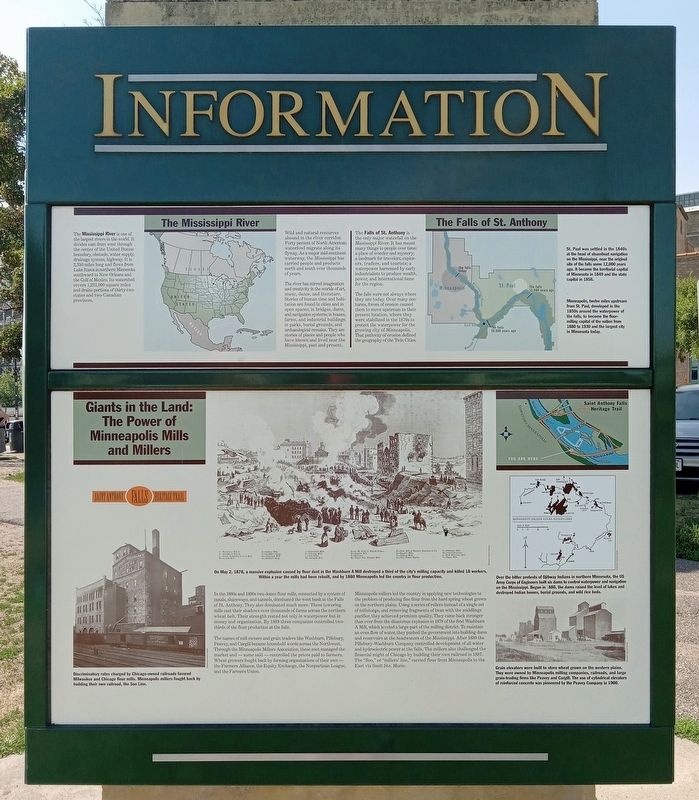

Giants in the Land: The Power of Minneapolis Mills and Millers

— Saint Anthony Falls Heritage Trail —

Inscription.

Discriminatory rates charged by Chicago-owned railroads favored Milwaukee and Chicago flour mills. Minneapolis millers fought back by building their own railroad, the Soo Line.

On May 2, 1878, a massive explosion caused by flour dust in the Washburn A Mill destroyed a third of the city's milling capacity and killed 18 workers. Within a year the mills had been rebuilt, and by 1880 Minneapolis led the country in flour production.

In the 1880s and 1890s two dozen flour mills, connected by a system of canals, sluiceways, and tunnels, dominated the west bank at the Falls of St. Anthony. They also dominated much more. These towering mills cast their shadows over thousands of farms across the northern wheat belt. Their strength rested not only in waterpower but in money and organization. By 1889 three companies controlled two-thirds of the flour production at the falls.

The names of mill owners and grain traders like Washburn, Pillsbury, Peavey, and Cargill became household words across the Northwest. Through the Minneapolis Millers Association, these men managed the market and—some said—controlled the prices paid to farmers. Wheat growers fought back by forming organizations of their own—the Farmers Alliance, the Equity Exchange, the Nonpartisan League, and the Farmers Union.

Minneapolis millers led the country in applying new technologies to the problem of producing fine flour from the hard spring wheat grown on the northern plains. Using a series of rollers instead of a single set of millstones, and removing fragments of bran with the middlings purifier, they achieved premium quality. They came back stronger than ever from the disastrous explosion in 1878 of the first Washburn A Mill, which leveled a large part of the milling district. To maintain an even flow of water, they pushed the government into building dams and reservoirs at the headwaters of the Mississippi. After 1889 the Pillsbury-Washburn Company controlled development of all water and hydroelectric power at the falls. The millers also challenged the financial might of Chicago by building their own railroad in 1887. The "Soo," or "millers' line," carried flour from Minneapolis to the East via Sault Ste. Marie.

Over the bitter protests of Ojibway Indians in northern Minnesota, the US Army Corps of Engineers built six dams to control waterpower and navigation on the Mississippi. Begun in 1880, the dams raised the level of lakes and destroyed Indian homes, burial grounds, and wild rice beds.

Grain elevators were built to store wheat grown on the western plains. They were owned by Minneapolis milling companies, railroads, and large grain-trading firms like Peavey and Cargill.

The use of cylindrical elevators of reinforced concrete was pioneered by the Peavey Company in 1900.

[panel above marker on kiosk]

The Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is one of the largest rivers in the world. It divides east from west through the center of the United States: boundary, obstacle, water supply, drainage system, highway. It is 2,350 miles long and flows from Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota southward to New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico. Its watershed covers 1,231,000 square miles and drains portions of thirty-two states and two Canadian provinces.

Wild and natural resources abound in the river corridor. Forty percent of North American waterfowl migrate along its flyway. As a major mid-continent waterway, the Mississippi has carried people and products north and south over thousands of years.

The river has stirred imagination and creativity in the worlds of art, music, dance, and literature. Stories of human time and habitation are found in cities and in open spaces; in bridges, dams, and navigation systems; in houses, farms, and industrial buildings; in parks, burial grounds, and archaeological remains. They are stories of places and people who have known and lived near the Mississippi, past and present.

The Falls of St. Anthony

The Falls of St. Anthony is the only major waterfall on the Mississippi River. It has meant many things to people over time: a place of wonder and mystery; a landmark for travelers, explorers, traders, and tourists; a waterpower harnessed by early industrialists to produce wealth, power, and international fame for the region.

The falls were not always where they are today. Over many centuries, forces of erosion caused them to move upstream to their present location, where they were stabilized in the 1870s to protect the waterpower for the growing city of Minneapolis. That pathway of erosion defined the geography of the Twin Cities.

St. Paul was settled in the 1840s, at the head of steamboat navigation on the Mississippi, near the original site of the falls some 12,000 years ago. It became the territorial capital of Minnesota in 1849 and the state capital in 1858.

Minneapolis, twelve miles upstream from St. Paul, developed in the 1850s around the waterpower of the falls, to become the flour-milling capital of the nation from 1880 to 1930 and the largest city in Minnesota today.

Erected by St. Anthony Falls Heritage Board.

Topics. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: Disasters • Industry & Commerce • Railroads & Streetcars • Waterways & Vessels. A significant historical year for this entry is 1878.

Location. 44° 58.859′ N, 93° 15.542′ W. Marker is in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in Hennepin County. It is in Downtown East. Marker can be reached from W. River Parkway west of Portland Avenue, on the right when traveling west. The marker is on a kiosk at the pay parking lot at the west end of the Stone Arch Bridge. Touch for map. Marker is at or near this postal address: 100 W River Parkway, Minneapolis MN 55401, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. Stone Arch Bridge (within shouting distance of this marker); Historic Milling District (within shouting distance of this marker); New Uses for Old Mills (within shouting distance of this marker); Mills and Millraces (within shouting distance of this marker); The Falls of St. Anthony (about 300 feet away, measured in a direct line); Water: The waterpower harnessed from St. Anthony Falls gave life to the milling industry (about 300 feet away); Bricks and Mortar (about 400 feet away); A Changing Landscape (about 400 feet away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Minneapolis.

Credits. This page was last revised on March 23, 2024. It was originally submitted on March 15, 2024, by McGhiever of Minneapolis, Minnesota. This page has been viewed 49 times since then. Photos: 1, 2. submitted on March 15, 2024, by McGhiever of Minneapolis, Minnesota.