Birmingham in Jefferson County, Alabama — The American South (East South Central)

Ironmaking

Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark

The Industry That Built A City

The minerals needed to make iron-iron ore, coal, and limestone-are abundant in the Birmingham area, and for ninety years men turned these materials into pig iron at Sloss. Sloss pig iron was sold to foundries, where it was melted down and cast into iron pipe, machinery, and many other products.

The heart of the Sloss plant was a pair of blast furnaces that together produced as much as 950 tons of iron a day. In addition to the furnaces, the plant consisted of a large number of auxiliary machines and structures: steam-powered engines to pump air; stoves to heat air; boilers to produce steam to drive the equipment; and a network of pipes to carry water, steam and gas. You will see all of this on your tour of Sloss.

The Raw Materials

Iron Ore

Sloss obtained its iron ore from company-owned mines at several locations in Alabama and, after about 1950, from Brazil and Peru as well. In Birmingham the principal source of ore was the Red Mountain formation, a ridge of hills on the southern flank of the city Red Mountain ore, known as hematite, contains from 35 to 38 percent iron. Company lands in northeast Alabama produced brown ore, or limonite, which has an iron content of 40 to 50 percent.

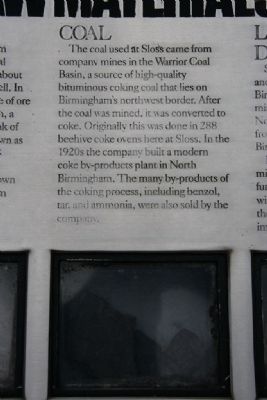

Coal

The coal used at Sloss came from company mines in the Warrior Coal Basin, a source of high-quality bituminous coking coal that lies on Birminghamís northwest border. After the coal was mined, it was converted to coke. Originally this was done in 288 beehive coke ovens here at Sloss. In the 1920s the company built a modern coke by-products plant in North Birmingham. The many by-products of the coking process, including benzol, tar, and ammonia, were also sold by the company.

Limestone and Dolomite

Substantial quantities of limestone and dolomite underlie the whole Birmingham area. Sloss obtained these minerals from company quarries in North Birmingham and Gadsden, and from other companies in the Birmingham area.

Limestone and dolomite are similar minerals. Both are used in the blast furnace as fluxes; that is, they combine with impurities to remove them from the ore. The combination of flux and impurities is called slag.

Air

The final raw material needed to make iron is air. Air for the furnace is preheated to a very high temperature and pumped into the furnace at high velocity. It is the blast of air that gives the blast furnace its name.

You will follow the path of the air and other raw materials as they travel to the furnace.

The People

Former workers report that at one time in the early 20th century nearly 2000 men worked at Sloss. The payroll gradually dwindled over the years as technological improvements reduced the number of men needed to work the furnace. Modernization of the plant in the late 1920s cut the payroll drastically. By the time Sloss closed in 1970 the number had reached a low of 250.

Many of the men who worked at Sloss lived nearby in company-owned housing called the Sloss Quarters. Designed specifically for black workers, the houses were typical shotgun-style structures, with two or three rooms set on foundation posts and no indoor plumbing. The company also ran a commissary, where workers could purchase an array of goods on credit, and sponsored community activities such as picnics and baseball teams. Although the Quarters were demolished in the mid-1950s, the commissary still stands just north of the viaduct at the 32nd Street exit from the Sloss grounds.

Over the years about 65 percent of the workers at Sloss were black. Still, the workplace was rigidly segregated until the mid-1960s. Men bathed in separated bathhouses, drank from separate water fountains, punched separate time clocks, attended separate company picnics. More important was the segregation of jobs. The plant operated as a hierarchy. At the top there was an all-white group of chemists, accountants, and engineers; at the bottom, an all-black “labor gang.” In the middle, a

Photographed By Tim & Renda Carr, June 22, 2011

3. Pig Iron

Pure metallic iron is never found in nature. Rather it exists as iron ores-compounds of iron with oxygen. Iron is separated from its ores in a process called reduction. Iron ore is heated by burning a carbon-rich fuel such as charcoal or coke, so that the carbon removes oxygen from the ore and leaves metallic iron. The freed iron melts, then is drained periodically from the furnace and cast into bars called pigs. The bar at the left, typical of machine-cast pigs, weighs about 40 pounds.

In this setting unionization played a complex and sometimes self-defeating role. The union brought higher wages and a shorter work day, better working conditions and safety standards, and increased personnel benefits. But opinions on its day-to-day effectiveness varied. White workers saw the union as an organization that worked for the common good. Black workers often acknowledged the benefitís the union won, but suffered from the unionís reluctance to fight job discrimination.

Like any institution that exists over a long period of time, Sloss underwent many changes - in management, in labor force, in social and economic context. The story of these changes is the history not just of a company, but of the men who built an industry and a city.

Erected by Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark.

Topics. This historical marker is listed in this topic list: Industry & Commerce. A significant historical year for this entry is 1950.

Location. 33° 31.254′ N, 86° 47.477′ W. Marker is in Birmingham, Alabama, in Jefferson County. Marker can be reached from the intersection of 32nd Street North and 2nd Avenue North. Marker is located near the base of the water tower on the grounds of Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark. Touch for map. Marker is at or near this postal address: Twenty 32nd Street North, Birmingham AL 35222, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. Sloss Quarters (within shouting distance of this marker); Slag (within shouting distance of this marker); The Gas System (within shouting distance of this marker); The Blast Furnace (within shouting distance of this marker); The Blowing Engine Room (within shouting distance of this marker); Boilers (within shouting distance of this marker); Casting Pigs (within shouting distance of this marker); The Stock Trestle (within shouting distance of this marker). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Birmingham.

Also see . . .

1. Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark website. (Submitted on June 30, 2011, by Timothy Carr of Birmingham, Alabama.)

2. Birmingham Rails. John Stewart, author of Birmingham Rails has done extensive research about the history of Birmingham's iron and steel industry. He has built very interesting website showing the former mines, mills, and the transportation system that linked them all together to produce the iron and steel which gave Birmingham the destiction of being the Pittsburg of the South. (Submitted on June 30, 2011, by Timothy Carr of Birmingham, Alabama.)

Photographed By Tim & Renda Carr, August 14, 2009

27. The Duncan House

The Duncan House was built in 1906 as a home place for James and Lella Duncan and their eight children in what is now Tarrant City, Alabama. Duncan worked throughout his life in the nearby shops and yards of the L&N. Railroad (now CSX) as water boy, conductor, and yard dispatcher.

Donated to Birmingham Historical Society in 1985 by Alabama By-Products Company, Inc. (now Drummond), Duncan House was moved to its current location at Sloss Quarters, the former site of Sloss company housing, for use as offices and to interpret the city's history.

The structure is representative of housing occupied by middle management during the period when Birmingham emerged as a major industrial center.

Credits. This page was last revised on June 16, 2016. It was originally submitted on June 30, 2011, by Timothy Carr of Birmingham, Alabama. This page has been viewed 1,574 times since then and 29 times this year. Photos: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27. submitted on June 30, 2011, by Timothy Carr of Birmingham, Alabama. • Bernard Fisher was the editor who published this page.