Hunt (Camp)

Minidoka Internment National Monument

— National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior —

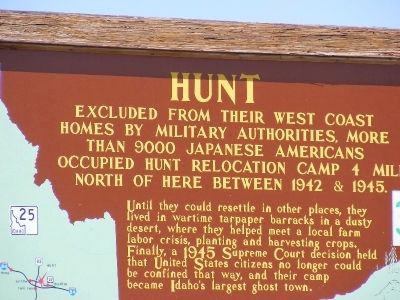

Excluded from their west coast homes by military authorities, more than 9000 Japanese Americans occupied Hunt Relocation Camp 4 miles north of here between 1942 & 1945.

Until they could resettle in other places, they live in wartime tarpaper barracks in a dusty desert, where they helped meet a local farm labor crisis, planting and harvesting crops. Finally a 1945 Supreme Court decision held that United States citizens no longer could be confined that way, and their camp became Idaho’s largest ghost town.

Erected by Idaho Historical Society and Idaho Transportation Department. (Marker Number 340.)

Topics and series. This memorial is listed in these topic lists: Asian Americans • War, World II. In addition, it is included in the Former U.S. Presidents: #33 Harry S. Truman, and the Idaho State Historical Society series lists.

Location. 42° 39.744′ N, 114° 17.106′ W. Marker is in Hunt, Idaho, in Jerome County. Memorial is on Hunt Road. Touch for map. Marker is in this post office area: Jerome ID 83338, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within 2 miles of this marker, measured as the crow flies. Prehistoric Hunters (about 300 feet away, measured in a direct line); Symbols of Imprisonment (approx. 2 miles away); Minidoka Relocation Center (approx. 2 miles away); Soothing Waters (approx. 2 miles away); On Guard (approx. 2 miles away); Minidoka National Historic Site (approx. 2 miles away); A Question of Loyalty (approx. 2.1 miles away); Honor Roll (approx. 2.1 miles away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Hunt.

Regarding Hunt (Camp). Minidoka National Historic Site

As the 385th unit of the National Park System, Minidoka was established in 2001 to commemorate the hardships and sacrifices of Japanese Americans interned there during World War II. Also known as 'Hunt Camp', Minidoka Relocation Center was a 33,000-acre site with over 600 buildings and a total population of about 13,000 internees from Alaska, Washington, and Oregon. The Center was in operation from August 1942 until October 1945.

Executive Order 9066

In the 1800s, many emigrants from Japan crossed the

Pacific Ocean to seek economic opportunity in America.

While some originally intended to return to their

birthplace, many eventually established families, farms, businesses, and communities in the United

objectives against sabotage and espionage. Although the order could be applied to all people, the focus was on persons of Japanese, German, and Italian decent. Due to public pressure the order was mainly used to exclude persons of Japanese ancestry, both American citizens and legal resident aliens, from coastal areas including portions of Alaska, Washington State, Oregon, southern Arizona, and all of California.

Japanese American Internment

During World War II

Following the signing of Executive Order 9066, over

120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry (Nikkei) living on the West Coast were forced to leave their homes, jobs, and businesses behind and report to designated military holding areas. This constituted the single largest forced relocation in U.S. history. Temporary assembly centerswere located at fairgrounds, eacetracks, and other make-shift facilities. Some 7,100 future Minidoka residents were first incarcerated at the Puyallup, Washington assembly center known as 'Camp Harmony'. Despite its innocuous name, it was no summer camp. Barbed wire fences surrounded the camp, armed guards patrolled the grounds, and movement between different areas of the camp was strictly controlled. It would be four to five months before the ten relocation centers established by the Wartime Relocation Authority

were ready for occupation.

Living Conditions at Minidoka

Minidoka's first internees arrived to find a camp still under construction. There was no hot running water and the sewage system had not been constructed. The initial reaction to the stark landscape by many was one of discouragement. Upon arriving, one internee wrote: "When we first arrived here we almost cried, and thought that this is the land God had forgotten. The vast expanse of nothing but sagebrush and dust, a landscape

Provisions within the barracks consisted of Army Issue

cots and a pot-bellied stove. Light was provided by a

single hanging bulb. Scraps of lumber and sagebrush were utilized to make furniture. Coal for the stoves and water had to be hand carried. When coal supplies ran low, sagebrush was gathered and burned. The hastily built barracks buildings were little more than

wooden frames covered with tarpaper. They had no

insulation. Temperatures during the winter of 1942

plunged to -21 degrees Fahrenheit. Over 100 tons of coal a day was needed for heating the buildings in the camp. Spring, with its ankle deep mud, was followed by. scorching heat with temperatures soaring to 104 degrees Fahrenheit and blinding dust storms. Two accidental drowning in the nearby North Side Canal prompted internees to build a swimming hole to cope with the oppressive heat.

Many living in the rural communities outside the camp

thought the internees, with their running water, indoor plumbing, and "free" supplies, were being "coddled", a view that still persists today. For those inside the camp, torn from their homes, friends and livelihoods, then confined within barbed wire fences and looking out at armed guards, the perception was considerably different. Despite the harsh conditions at Minidoka, internees were

resourceful. They built baseball diamonds and small

parks with picnic areas. Their baseball team was

virtually unbeatable. Taiko drumming and other

musical groups were formed, and a newspaper was

published, the Minidoka Irrigator. To create beauty in an otherwise dismal landscape, paths were lined with decorative stones and traditional Japanese gardens were planted. Some of these remnants are still visible today, yet most traces of daily life at

Minidoka are now gone.

Wartime Efforts

The relocation centers were subject to the same wartime rationing as the rest of the .country. Materials considered to be vital to the war effort were recycled. Minidoka was nearly an entirely self-sustaining community complete with vegetable gardens and hog and chicken farms. Japanese Americans interned at Minidoka were also an indispensable source of labor for

A Question of Loyalty

Segregation in the camps was achieved by employing

what came to be known as the "loyalty questionnaire."

The questionnaires were originally designed for determining suitability for military service, however two problematic questions emerged. Question 27 asked all internees if they would be willing to serve in the Armed Forces on combat duty "wherever ordered." Women and legal aliens who were not allowed to serve in combat struggled with this question. Question 28 asked internees to foreswear allegiance to Japan. The

Issei, forbidden to become US citizens, were troubled by the implications of this question. Those who answered "no" to both questions were labeled the "No-No's" and shipped to Tule Lake, California, the camp for 'dissenters'. Many at Tule Lake who answered "yes" to both questions were shipped to Minidoka, a camp for 'loyal' internees.

The 442nd Regimental Combat Unit

Despite their internment, most Japanese Americans

remained intensely loyal to the United States, and many demonstrated their loyalty by volunteering for military service. They were segregated into all Japanese American combat and intelligence units commanded by non-J apanese Americans. Of the ten relocation centers, Minidoka had the highest number of volunteers, about 1,000 internees - nearly ten percent of the camp's total peak population.

The 442nd combat unit fought in France and Italy

alongside the 10th Infantry Battalion from Hawaii (also composed of Japanese Americans) and was the most

highly decorated unit of its size in American military

history. During WWII, 73 soldiers from Minidoka died

while fighting for their country and two received the

Congressional Medal of Honor. "You fought not only the enemy but you fought prejudice and you have won." -President Truman addressing members of the

442nd at the White House in 1946

Camp Closing

During the years of incarceration the internees had

transformed many acres of high desert into viable

agricultural land. After the camp closed in October 1945, the land was subdivided into smaller farms and

auctioned to the highest bidders or given to WWII

veterans along with two barracks buildings and one

smaller building. The

Could This Happen Again?

The incarceration of Japanese Americans during the

1940s has been described as one of the worst violations of constitutional rights in American history and yet few Americans raised their voices in protest of the removal order. More than two-thirds of the internees were American citizens by birth. The system of checks and balances that was suppose to protect their rights and freedoms had failed.

In 1988, the Civil Liberties Act acknowledged the

fundamental injustice of the evacuation, relocation, and internment of citizens and permanent resident aliens of Japanese ancestry during World War II.

A formal apology by the U.S. Government was made, as

well as restitution to those individuals who were interned. And most importantly, the Act provides for a public education fund to finance efforts to inform the public about the internment so as to prevent the recurrence of any similar event. The Historic Site preserves remnant features from the original camp such

as the waiting room at the entrance station. •NPS

Photo

All photographs courtesy of Records of the War

Relocation Authority, Record Group 210; National

Archives at College Park, College Park, MD 20740

(unless otherwise labeled)

Directions

Preserving the Historic Site

Collecting of artifacts, rocks, plants, animals, or any

other object within the National Historic Site is strictly

prohibited. Help preserve your park by taking only

memories and photographs. Report violations to the

National Park Service at (208) 837-4793.

May We also Suggest:

Websites: www.nps.gov/manz

www.minidoka.org

www.historicaljeromecounty.com

Visit the Minidoka Relocation Center display at the

Jerome County Museum and the "restored" barracks

. building at the Idaho Farm and Ranch Museum

(IFARM).

Jerome County Historical Society and IFARM,

220 N. Lincoln, Jerome, Idaho 83338

(208) 324-5641

Minidoka National Historic Site is located between the

towns of Twin Falls and Jerome, Idaho in south central

Idaho. The Historic Site is open to the public, portapotties

and parking are located at the west entrance.

Guided tours are by appointment only.

To get to the Historic Site from the intersection of

Interstate 84 (1-84) and U.S. Highway 93 (US 93): Travel

north on US 93 for 5 miles to the Eden exit. Travel east

on Highway 25 for 9.5 miles to the Hunt Rd. exit. Travel

east on Hunt Rd. for 2.2 miles to the small parking area

on your right.

(NATIONAL PARK SERVICE BROCHURE)

Additional commentary.

1. Marker Location

The marker is located approximately 2.5 miles southwest from the western entrance to the Minidoka National Historic Site. The marker is located at the intersection of Hunt Road and State Route 25 (Geo-coordinates: 42.662395, -114.2851).

Credits. This page was last revised on May 6, 2021. It was originally submitted on December 19, 2012, by Don Morfe of Baltimore, Maryland. This page has been viewed 1,909 times since then and 224 times this year. Photos: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. submitted on December 19, 2012, by Don Morfe of Baltimore, Maryland. • Bill Pfingsten was the editor who published this page.