Near Adrian in Nobles County, Minnesota — The American Midwest (Upper Plains)

Fire on the Prairie

Fire can be incredibly destructive in nature. However, it is also an integral part of the tallgrass prairie ecosystem. Over thousands of years, this ecosystem adapted to drought and fire and became dependent on it.

Historically, some prairie fires started due to lightning, and others started because American Indians used fire for hunting bison and making travel easier. Burning prairies in the fall caused plants to grow earlier in the spring. This attracted grazing bison.

Frequent fires slow down the invasion of trees and shrubs from the edge of the prairie. This maintains the grasslands and treeless structure of the prairie. Fires also burn up old plant litter, release nutrients into the ground and expose soils that warm faster in the spring. Warm soils increase seed germination and growth of prairie grasses.

Prairie plants survive fires because 50 to 80 percent of the plant is underground. Plants can quickly re-grow using energy and nutrients stored in their undamaged roots.

(Caption)

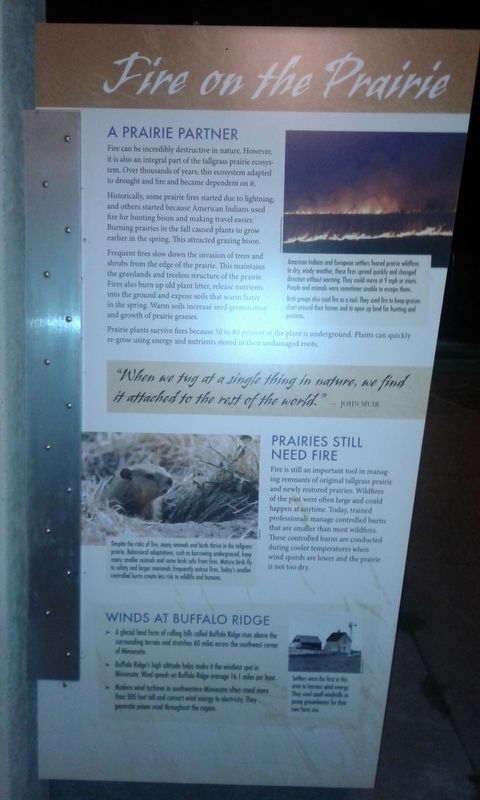

American Indians and European settlers feared prairie wildfires. In dry, windy weather, these fires spread quickly and changed direction without warning. They could move at 9 mph or more. People and animals were sometimes unable to escape them.

Both groups also used fire as a tool. They used fire to keep grasses short ground their homes and to open up land for hunting and pastures.

"When we tug at a single thing in nature, we find it attached to the rest of the world.” - John Muir

Prairies Still Need Fire

Fire is still an important tool in managing remnants of original tallgrass prairie and newly restored prairies. Wildfires of the past were often large and could happen at anytime. Today, trained professionals manage controlled burns that are smaller than most wildfires. These controlled burns are conducted during cooler temperatures when wind speeds are lower and the prairie is not too dry.

(Caption)

Despite the risks of fire, many animals and birds thrive in the tallgrass prairie. Behavioral adaptations, such as burrowing underground, keep many smaller animals and some birds safe from fires. Mature birds fly to safety and larger mammals frequently outrun fires. Today's smaller controlled burns create less risk to wildlife and humans.

Winds At Buffalo Ridge

➤ A glacial land form of rolling hills called Buffalo Ridge rises above the surrounding terrain and stretches 60 miles across the southwest corner of Minnesota.

➤ Buffalo Ridge's high altitude helps make it the windiest spot in Minnesota. Wind speeds on Buffalo Ridge average 16.1 miles per hour.

➤ Modern wind turbines in southwestern Minnesota often stand more than 300 feet tall and convert wind energy to electricity. They generate power used throughout the region.

(Caption)

Settlers were the first in this area to harness wind energy. They used small windmills to pump groundwater for their own farm use.

(Side 2)

Tallgrass Prairie

Tallgrass prairie gets its name from some species of grass that reach more than six feet tall by late summer. Some call it an upside-down forest, because roots can reach more than 15 feet underground. This ecosystem boasts more than 900 recorded plant species.

Prairie plants massive root systems can stay alive for decades, and the prairie is always changing. In spring, the shorter plants bloom while the taller plants sprout. In summer, early season plants die back and tall grasses and flowers dominate the landscape. Non-native plants with shallow roots cannot compete with a healthy prairie. An established tallgrass prairie with natural processes such as fire can effectively stop non-native plants from growing.

(Caption)

Some prairie roots extend more than 15 feet underground and provide many environmental benefits. They control erosion, filter water, resist growth of non-native plants and enrich the topsoil when they decompose. These dense root masses also allow the plants to resist the effects of drought.

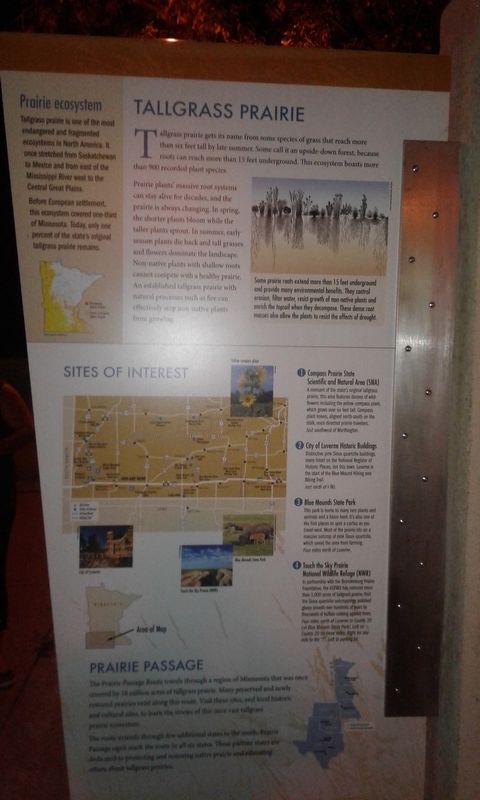

Prairie ecosystem

Tallgrass prairie is one of the most endangered and fragmented ecosystems in North America. It once stretched from Saskatchewan to Mexico and from east of the Mississippi River west to the Central Great Plains.

Before European settlement, this ecosystem covered one-third of Minnesota. Today, only one percent of the state's original tallgrass prairie remains.

Sites of Interest

1 Compass Prairie State Scientific and Natural Area (SNA)

A remnant of the state's original tallgrass prairie, this area features dozens of wildflowers including the yellow compass plant, which grows over six feet tall. Compass plant leaves, aligned north-south on the stalk, once directed prairie travelers.

Just southwest of Worthington.

2 City of Luverne Historic Buildings

Distinctive pink Sioux quartzite buildings, many listed on the National Register of Historic Places, dot this town. Luverne is the start of the Blue Mound Hiking and Biking Trial.

Just north of I-90.

3 Blue Mounds State Park

This park is home to many rare plants and animals and a bison herd. It's also one of the first places to spot a cactus as you travel west. Most of the prairie sits on a massive outcrop of pink Sioux quartzite, which saved the area from farming.

Four miles north of Luverne.

4 Touch the Sky Prairie National Wildlife Refuge (NWR)

In partnership with the Brandenburg Prairie Foundation, the USFWS has restored more than 1,000 acres of tallgrass prairie. Visit the Sioux quartzite outcroppings polished glassy smooth over hundreds of years by thousands of buffalo rubbing against them.

Four miles north of Luverne to County 20 (at Blue Mounds State Park). Left on County 20 for three miles. Right for one mile to the "T". Left to parking lot.

Prairie Passage

The Prairie Passage Route travels through a region of Minnesota that was once covered by 18 million acres of tallgrass prairie. Many preserved and newly restored prairies exist along this route. Visit these sites, and local historic and cultural sites, to learn the stories of this once vast tallgrass prairie ecosystem.

The route extends through five additional states to the south. Prairie Passage signs mark the route in all six states. These partner states are dedicated to protecting and restoring native prairie and education others about tallgrass prairies.

Topics. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: Horticulture & Forestry • Native Americans.

Location. 43° 38.215′ N, 95° 58.887′ W. Marker is near Adrian, Minnesota, in Nobles County. Marker is on Interstate 90, on the right when traveling east. Located at the Adrian Rest Area - Eastbound. Touch for map. Marker is in this post office area: Adrian MN 56110, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 3 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. A Sea of Grass (within shouting distance of this marker); Military Highways (approx. ¾ mile away); Prairie Life (approx. ¾ mile away).

Credits. This page was last revised on April 23, 2022. It was originally submitted on December 6, 2020, by Craig Doda of Napoleon, Ohio. This page has been viewed 123 times since then and 8 times this year. Photos: 1, 2. submitted on December 6, 2020, by Craig Doda of Napoleon, Ohio. 3. submitted on November 27, 2021, by Craig Doda of Napoleon, Ohio. 4. submitted on April 21, 2022. • Bill Pfingsten was the editor who published this page.