Ashland in McDowell County, West Virginia — The American South (Appalachia)

No Work Tomorrow

— National Coal Heritage Trail —

During the period from 1890 to 1930, the coal mines of the nation were operated only two-thirds of full time. This was partly due to strikes and lockouts, a result of periodic clashes between the coal operators and the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). The main cause of idleness was the lack of market demand for coal. By 1910 the industry as a whole had reached a state of overexpansion and the potential supply of coal was greater than the nation could consume. Lacking orders for their coal or the railroad cars to ship it, coal operators were forced to shut down periodically, resulting in lost wages for miners.

Southern West Virginia’s miners were somewhat more fortunate. However, the lack of demand for their product and the lack of railroad cars still existed. At this time, the activities of the UMWA were restricted in the region, resulting in fewer work stoppages due to strikes and lockouts. They worked on average 231 days during this period. Some years were better than others. During the World War I period, when coal was in great demand, miners worked nearly full time, but during the 1920s anti 1930s, when overexpansion became more pronounced, miners were idle nearly as much as they were on the job. For example, in 1921, West Virginia’s miners worked only an average of 149 days, slightly less than half time.

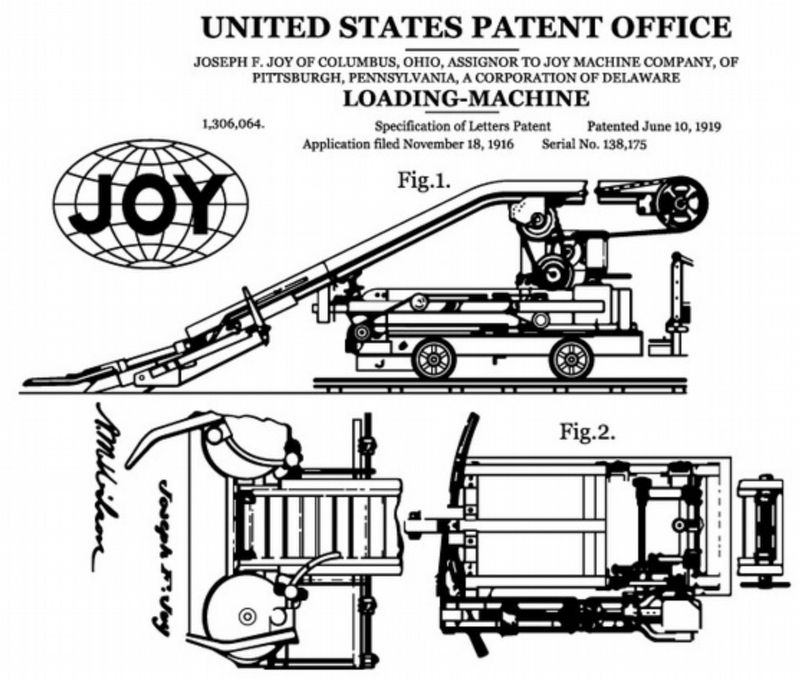

The next threat to coal miners’ livelihoods came with mechanization. The first cutting machines were introduced in the 1890s, but the full force of mechanization came with the installation of loading machines in the 1930s and 1940s, then the introduction of continuous milling in the 1950s and 1960s. As a result, thousands of miners lost their jobs to machines. The impact of this widespread unemployment was more sorely felt in southern West Virginia than in other part of the nation.

The impact of mechanization on employment in southern West Virginia was felt first by black coal miners, who made up nearly one-third of the total mining labor force. Loading machines, with the Joy loader as the industry standard, rapidly displaced black miners during the 1930s and 1940s. One black miner recalled that the mine management “always put them (loading machines) where blacks were working first.” “Black men,” he said, “could not kick against the machine.” Many black miners and their families left the region. By 1980, the number of black miners in the state had declined by over 90 percent.

After reaching a peak of 125,000 miners in 1947, employment in the state plummeted to 65,000 by 1954, and then to 49,000 in 1960. Widespread unemployment decimated mining communities in southern West Virginia. Coal companies abandoned their towns as thousands of miners unable to find work in the coalfields left to find manufacturing jobs in Ohio or Michigan.

(sidebar)

After organizing nearly all of the nation’s miners under its banner in 1933, the miners’ union agreed to support mechanization in return for a share of the benefits from increased productivity, including higher wages, a seniority system to protect jobs, and eventually, a welfare and retirement fund to provide cradle to grave care for miners and their families. John L. Lewis, President of the UMWA, realized that mechanization would result in the loss of thousands of mining jobs, but saw it as the only way to solve the industry’s chronic problem of overexpansion.

(sidebar)

Tell me, what will a coal miner do?

Tell me, what will a coal miner do?

When he goes down in the mine,

Joy loaders he will find.

Tell me, what will a coal miner do?

—“The Coal Loading Machine,” by George Korson

Erected by National Coal Highway Authority and America’s Byways.

Topics. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: Industry & Commerce • Labor Unions • Natural Resources. A significant historical year for this entry is 1890.

Location. 37° 24.526′ N, 81° 21.23′ W. Marker is in Ashland, West Virginia, in McDowell County. Marker is on Cherokee Road (County Route 17) 5.8 miles east of Coal Heritage Road in Northfork (U.S. 52), on the right when traveling east. Touch for map. Marker is in this post office area: Northfork WV 24868, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within 7 miles of this marker, measured as the crow flies. The Company Store (here, next to this marker); Ashland Coal and Coke (here, next to this marker); Young Miners (a few steps from this marker); Miners’ Pay (a few steps from this marker); Elizabeth Simpson Drewry (approx. 4.6 miles away); Bramwell (approx. 6.1 miles away); Mill Creek Coal & Coke Co. (approx. 6.1 miles away); The Coal Barons (approx. 6.2 miles away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Ashland.

More about this marker. Three photographs on this interpretive panel are captioned as follows, top to bottom:

- (an uncaptioned photograph showing miners at a sign reading “no work tomorrow”)

- a loading machine in operation

- John L. Lewis speaking at a rally

Also see . . . Song: Coal Loading Machine. Sung by the Evening Breezes Sextet of Vivian, West Virginia and recorded by George G. Korson. Issued in 1965 by the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress on the Long-Playing vinyl disk recording “Songs and Ballads of the Bituminous Miners.”

(Submitted on August 6, 2021.)

Photographed By J. J. Prats, July 24, 2021

4. National Coal Heritage Area Trail Interpretive Stop, Ashland WV

The sign all the way to the left shown in profile is not a historical marker. It is the sign for the Interpretive stop. The small sign on a single post all the way on the right has a map of the Coal Heritage Trail and lists points of interest along the trail.

This historical marker is the reclining sign at center left.

Credits. This page was last revised on August 6, 2021. It was originally submitted on August 6, 2021, by J. J. Prats of Powell, Ohio. This page has been viewed 147 times since then and 10 times this year. Photos: 1, 2, 3, 4. submitted on August 6, 2021, by J. J. Prats of Powell, Ohio.