Manassas, Virginia — The American South (Mid-Atlantic)

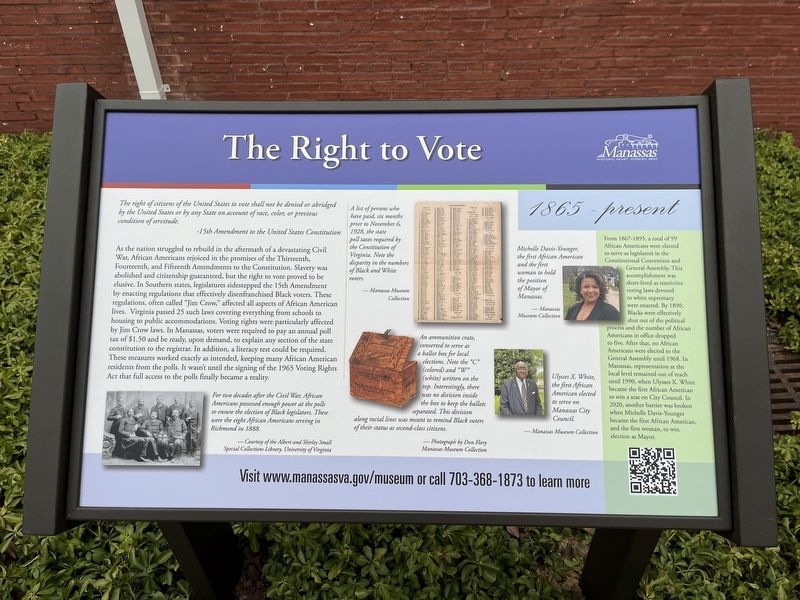

The Right to Vote

1865 - present

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

— 15th Amendment of the United States Constitution

As the nation struggled to rebuild in the aftermath of a devastating Civil War, African Americans rejoiced in the promises of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution. Slavery was abolished and citizenship guaranteed, but the right to vote proved to be elusive. In Southern states, legislatures sidestepped the 15th Amendment by enacting regulations that effectively disenfranchised Black voters. These regulations, often called "Jim Crow," affected all aspects of African American lives. Virginia passed 25 such laws covering everything from schools to housing to public accommodations. Voting rights were particularly affected by Jim Crow laws. In Manassas, voters were required to pay an annual poll tax of $1.50 and be ready, upon demand, to explain any section of the state constitution to the registrar. In addition, a literacy test could be required. These measures worked exactly as intended, keeping many African American residents from the polls. It wasn't until the signing of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that full access to the polls finally became a reality.

[Sidebar:]

From 1867 - 1895, a total of 99 African Americans were elected to serve as legislators in the Constitutional Convention and General Assembly. This accomplishment was short-lived as restrictive voting laws devoted to white supremacy were enacted. By 1890, Blacks were effectively shut out of the political process and the number of African Americans in office dropped to five. After that, no African Americans were elected to the General Assembly until 1968. In Manassas, representation at the local level remained out of reach until 1990, when Ulysses X. White became the first African American to win a seat on City Council. In 2020, another barrier was broken when Michelle Davis-Younger became the first African American, and the first woman, to win election as Mayor.

[Captions:]

For two decades after the Civil War, African Americans possessed enough power at the polls to ensure the election of Black legislators. These were the eight African Americans serving in Richmond in 1888.

— Courtesy of the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia

A list of persons who have paid, six months prior to November 6, 1928, the state poll taxes required by the Constitution of Virginia. Note the disparity in the numbers of Black and White

— Manassas Museum Collection

An ammunition crate, converted to serve as a ballot box for local elections. Note the "C" (colored) and "W" (white) written on the top. Interestingly, there was no division inside the box to keep the ballots separated. This division along racial lines was meant to remind Black voters of their status as second-class citizens.

— Photograph by Don Flory

Manassas Museum Collection

Michelle Davis-Younger, the first African American and the first woman to hold the position of Mayor of Manassas.

— Manassas Museum Collection

Ulysses X. White, the first African American elected to serve on Manassas City Council.

— Manassas Museum Collection

Erected by City of Manassas, Virginia.

Topics. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: African Americans • Civil Rights. A significant historical date for this entry is November 6, 1928.

Location. 38° 45.067′ N, 77° 28.239′ W. Marker is in Manassas, Virginia. Marker is at the intersection of Center Street (Virginia Route 28) and East Street, on the right when traveling east on Center Street. Touch for map. Marker is at or near this postal address: 9027 Center St, Manassas VA 20110, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. Steam Locomotive Tire Fire Alarm – 1909 (here, next to this marker); Harry J. Parrish (a few steps from this marker); Wartime Manassas (a few steps from this marker); Defenses of Manassas (about 300 feet away, measured in a direct line); Manassas 1906 (about 300 feet away); 9366 Main Street (about 300 feet away); Our Story Continues (about 300 feet away); a different marker also named Wartime Manassas (about 400 feet away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Manassas.

Credits. This page was last revised on January 8, 2023. It was originally submitted on January 8, 2023, by Devry Becker Jones of Washington, District of Columbia. This page has been viewed 94 times since then and 23 times this year. Photos: 1, 2. submitted on January 8, 2023, by Devry Becker Jones of Washington, District of Columbia.