Niagara Falls in Niagara County, New York — The American Northeast (Mid-Atlantic)

Escape Prevented

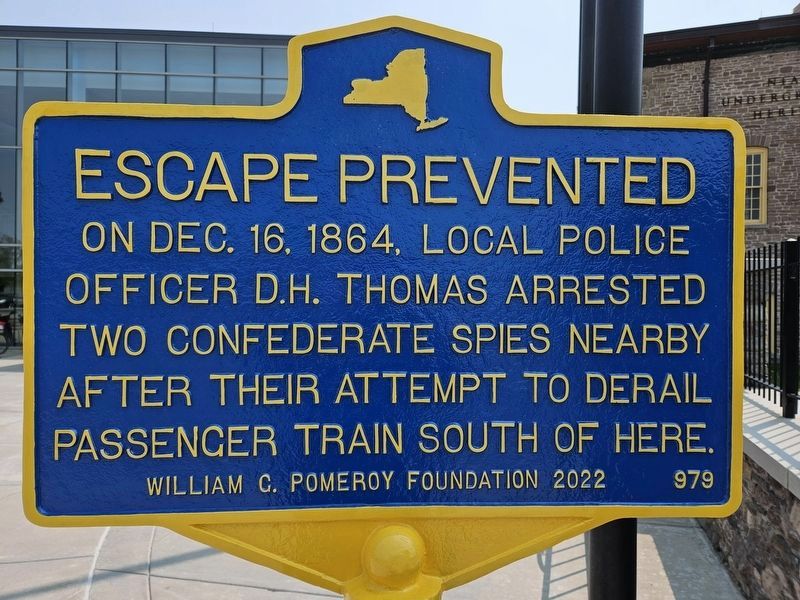

Inscription.

On Dec. 16, 1864, local police officer D.H. Thomas arrested two Confederate spies nearby after their attempt to derail passenger train south of here.

Erected 2023 by William G. Pomeroy Foundation & Niagara Frontier Chapter, National Railway Historical Society. (Marker Number 979.)

Topics and series. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: Law Enforcement • Railroads & Streetcars • War, US Civil. In addition, it is included in the William G. Pomeroy Foundation series list. A significant historical date for this entry is December 16, 1864.

Location. 43° 6.601′ N, 79° 3.325′ W. Marker is in Niagara Falls, New York, in Niagara County. Marker is at the intersection of Depot Avenue West and Whirlpool Street, on the left when traveling west on Depot Avenue West. Marker is at the Amtrak Station. Touch for map. Marker is at or near this postal address: 825 Depot Avenue West, Niagara Falls NY 14305, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. United States Custom House (within shouting distance of this marker); First Niagara Suspension Bridge (about 500 feet away, measured in a direct line); A Bridge to Freedom (about 600 feet away); Great Gorge Railway Trail (about 600 feet away); To The River (about 600 feet away); About the year 1600 B.C. ... (approx. 0.3 miles away in Canada); The Inukshuk (approx. 0.6 kilometers away in Canada); Pastimes and Parkways (approx. 0.9 kilometers away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Niagara Falls.

Regarding Escape Prevented. This following remarks were delivered by Anton Schwarzmueller at the dedication of the marker on 20 May 2023.

Thank you all for coming here today to dedicate this historical marker in honor of a forgotten local policeman and his act of arresting a pair of Confederate spies in the later throes of the Civil War. Who were these two spies? George S. Anderson, age 17, who testified against the other, Captain John Yates Bell – spelled B E A L L.

First, let’s talk about Beall before he began operating in Canada.

Beall was from a county in Virginia that is now in West Virginia, near Harper’s Ferry. He studied law for a time at the University of Virginia but did not finish; he returned home upon his father’s death.

At the start of the war Beall joined the 2nd Virginia Infantry. He soon suffered a gunshot to the lung. While recovering, he conceived of rendering service to the

Confederacy as a raider in the Chesapeake Bay. To become a raider, he sought a discharge from the Confederate army in February 1863 based on his injury and was conferred the title of “Acting Master” by the Confederacy, “Master” meaning master of a ship. He would act as a privateer, which is a private person or ship authorized by a government to engage in warfare. The Confederacy provided him no ships, no men, no salaries, no uniforms – only a title that might be recognized as protection in case he were taken prisoner.

Beall somehow acquired two ships, the Swan and the Raven. With 25 men, the two ships began their raiding. This was after the famous battle between the ironclads Monitor and Merrimac. Beall’s ships would hide in small inlets in Mathews County, Virginia, on the Chesapeake Bay, which is north of Yorktown. The men would hide in barns and fishing shacks between forays. Beall was not the sole raider on the Bay, but he was the most infamous.

What were some of Beall’s maritime deeds at this time in the Chesapeake? He cut the telegraph wires to Ft. Monroe, trashed the South Island lighthouse, stole a ship full of whale oil (which is what we used before the oil pumped from underground), and burned a captured schooner. His capture of several sloops and the schooner J.J. Houseman bloodied his hands. The African-American cook of that ship, that was carrying supplies to Ft. Monroe, jumped overboard. Beall’s raiders fired pistols at the cook, who decided to surrender and reboard the ship. Once on board, Beall’s men shot the man dead, throwing his body in the Chesapeake, weighted down with iron.

The Union became increasingly angered by the partisan Confederate raiders. Eventually, Union troops and gunboats under Major General Isaac Jones Wistar were assigned to weed-out Beall and his men in Mathews County. A Union gunboat found Swan and Raven in a cove. 17 men, including Beall, were captured in November 1863. Months later, Beall was paroled from Ft. McHenry in Baltimore in a prisoner exchange, and took the opportunity rejoin the war effort, this time from neutral British Canada, which was his actually first idea, before becoming a raider on the Chesapeake.

On Johnson Island on Lake Erie in Ohio, the Union had a prison for Confederate Officers. Beall wanted to repatriate them by capturing the only Union warship on the Great Lakes by treaty: The USS Michigan. The risk of inciting the neutral British in Canada had become less concerning to the Confederacy as they became more desperate. Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederacy, approved the operation.

On 19 September 1864, the steamer Philo Parsons departed Detroit. As requested by a passenger the day before, the steamer then crossed the Detroit River to Sandwich (now Windsor) in Canada where three men in civilian clothes, including Beall, boarded. They had no luggage. At Amherstburg, Canada, also on the Detroit River, 25 more men boarded. Their only luggage was an old trunk. The men, led by Beall, commandeered the boat as it neared Sandusky, Ohio. The old trunk contained their weapons: revolvers and hatchets. A passenger testified that the men called their leader Captain Beall. The men put out the passengers on Middle Bass Island and took on wood while another boat the Island Queen came alongside. The Confederates seized this boat as well, and took 20-25 unarmed Union soldiers as prisoners who were traveling to be mustered out of service. The soldiers were put ashore, and the boat was scuttled. The Philo Parsons was taken to Amherstburg because the rebels would not agree to take part in life-risking endeavor to take the USS Michigan.

When news of this event reached Niagara, coupled with the raid of St. Albans, VT from Canada by Confederates, our area was put on alert. The Niagara Gazette reported on November 2nd 1864, “A strong guard has been placed at both ends of the Suspension Bridge and the night lanterns are kept filled with oil. The firemen and police have been placed on alert and will be subject to call at any moment. Company B of the 90th NY National Guard patrolled the streets. A detachment of soldiers from Rochester came. A 9’ long 150 caliber musket was set up at the bridge.

Today’s Whirlpool Rapids Bridge is exactly where the Suspension Bridge was located; and configured the same, with vehicular traffic on the lower deck and train track on the upper deck.

Next, Beall and others, led by Colonel William T. Martin, conspired to rob a train between Buffalo and Dunkirk. 17-year-old Confederate Anderson rode a train with the Colonel and a Lieutenant Hadley to Dunkirk, the plan being to “capture” a train on the way back to Buffalo, but this was not done. They walked five or six miles south of Buffalo, Beall joining them along the way. They tried to pull a rail out of place with a sledge – possessed by Beall - and a chisel but failed. They fled to Port Colborne in Canada, stayed a day, and returned with a fifth man for another try. They procured a sleigh, went five miles south, but they missed the train. They stayed overnight at a hotel and tried again at 2 o’clock on December 16, 1864, placing a rail across the tracks. This failed to derail the train.

Trains of 1864 were very different from the trains of today. Passenger coaches were mostly of wood and heated by wood stoves. Derailing a passenger train could have horrific results, with coaches smashing apart and catching fire from the stoves. These Confederate saboteurs had no qualms about causing death and injury to innocent civilians. In the language of today we call them terrorists. It reflected the desperation of the Confederacy to convince the Union populace to end the war before winning it.

Now Beall and Anderson were in the New York Central passenger depot on Depot Avenue between 9th and 10th Streets at 9 or 10 o’clock at night on December 16th, 1864, waiting for the 11 o’clock train to Canada. Officer David H. Thomas of the village of Niagara City (aka: Suspension Bridge) and his partner by the name of Saules, approached Beall and Anderson. Officer Thomas questioned Beall. Initially Beall identified himself as John Beall, then claimed he was W.W. Baker, the name of one of his cohorts in the Chesapeake raids. Beall denied that he said he was John Beall. Both Beall and Anderson were in civilian clothes, and Beall was in possession of a loaded Colt firearm. Officer Thomas arrested them, accusing Beall of being an escaped prisoner from Point Lookout, Chesapeake Bay. This was a Union prison in Maryland at the mouth of the Potomac River. To this Beall admitted, though it was false, later stating that he had gone to Baltimore and from there to escape to Canada. He added that he had vowed not to be taken and would have shot Officer Thomas had the officer not come to him so suddenly or unexpectedly.

John Yates Beall was brought to Fort Lafayette in New York City, a fort that had been repaired and improved in the 1840s by an engineer named Robert E. Lee. Major General Dix, for whom Fort Dix is named, ordered a trial of Beall on January 17, 1865 to commence on January 20. After adjournments for preparation, the charges against Beall were read on February 1st. Six specifications for the charge of Violation of the Laws of War were entered: Three for acting as a spy and the other three specifications as follows: For seizing by force the steamboat Philo Parsons; for seizing and sinking the steamboat Island Queen on the same day; and that Beall, regarding the events of December 1864, “…did undertake to carry on irregular and unlawful activity as a guerrilla…attempted to destroy the lives and property of the peaceable and unoffending inhabitants of said [NY] state, and persons therein traveling, by throwing a train of cars and the passengers in said cars from the railroad track, on the railroad between Dunkirk and Buffalo, by placing obstructions across said track.” Beall pleaded not guilty.

The military tribunal found Beall guilty on all charges. General Dix, on February 14th, commanded Beall to be hanged at Fort Columbus on Governor’s Island, New York City, on February 24th. When the trial and sentence became public knowledge, entreaties to President Lincoln poured in to spare Beall, including from 92 members of Congress – none of them of Lincoln’s party. The Confederacy had brought terrorism to the people of the Union through Beall, the St. Albans Vermont raid, and a plot to set New York City ablaze. Lincoln would not be persuaded to interfere with General Dix’s sentence. Beall was unrepentant to the end.

Policeman David H. Thomas, who’s name appears on the marker, who arrested the two Confederates, preventing their escape to Canada, preventing them from committing further acts of terrorism, was at his life’s end a station master of the Erie Railroad, residing near Division and Main Streets here. He was found dead in the railroad yard, his death recorded as January 24, 1887. He died alone. Dying alone was considered to be a bad death by society at that time. He was 60 years old.

The respect and reverence shown by the community for David Thomas were reflected in the large gathering for his funeral. His casket was escorted from home to church by the Knights of Honor, the Chosen Friends, the International Order of Odd Fellows, and the fire department for which he once served as chief. Railroad men attending were from the Erie Railroad, the New York Central Railroad, the Nickel Plate Railroad, the Lehigh Valley Railroad, and the Union Pacific Railroad. He left behind two daughters, being predeceased by his wife. We have no images of him, and he seems to be without living descendants.

Even in death, he served the public. How? By being one of the earliest cremations in the area – a controversial practice at the time, meant for the betterment of public health. His remains are buried in Oakwood Cemetery.

And so today we resurrect the name of a local hero from the dustbin of history.

Also see . . . Grave of D.H. Thomas - Find A Grave. (Submitted on November 8, 2023, by Anton Schwarzmueller of Wilson, New York.)

Credits. This page was last revised on November 8, 2023. It was originally submitted on May 22, 2023, by Anton Schwarzmueller of Wilson, New York. This page has been viewed 110 times since then and 22 times this year. Photos: 1, 2. submitted on May 22, 2023, by Anton Schwarzmueller of Wilson, New York.