Near Rhame in Bowman County, North Dakota — The American Midwest (Upper Plains)

Fort Dilts Historic Site

Erected 1952 by Local Residents.

Topics. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: Forts and Castles • Native Americans • Railroads & Streetcars • Wars, US Indian. A significant historical month for this entry is September 1864.

Location. 46° 16.744′ N, 103° 46.589′ W. Marker is near Rhame, North Dakota, in Bowman County. Marker is on Fort Dilts Road, on the left when traveling west. Fort Dilts Road is a gravel road off of U.S.12 near mile marker 16. Site is 2 miles north and then 2 miles west. Touch for map . Marker is in this post office area: Rhame ND 58651, United States of America. Touch for directions.

More about this marker. (Taken from Nomination Form, National Register of Historic Places, U.S. Dept. of the Interior)

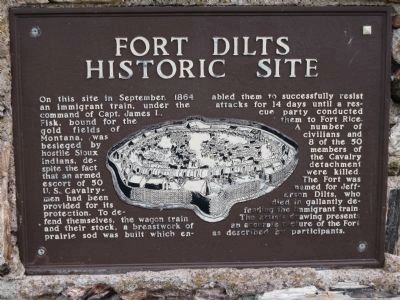

Fort Dilts was the site in 1864 of an extended siege of a circled wagon train by Sioux Indians. A six and a half foot high defensive fortification of sod and compacted earth was thrown up around the wagons after the train circled up at a commanding position near the summit of a ridge of hills. The fortification was roughly circular, with bastions on the north and south and an opening on the west. Approximately 300 feet in diameter, the fortification now exists as a low grass-covered ring with a shallow trench along the exterior side. Ruts cut into the native sod by the heavy wagons of the train are visible to the east of the earthwork and extend into the interior of the fortification.

Eight military marble headstones on the site commemorate soldiers of the escort who died in defense of the wagon train. Three headstones located along the northwest quarter of the ring represent three soldiers interred under the fortification wall. Five other headstones just outside the northern perimeter of the fortification commemorate soldiers who were killed in the siege and buried at unknown other locations. The headstones were provided by the 'Department of the Army and were placed on the site in 1933. A monument of local petrified wood and scoria was constructed just west of the ring in 1952 by area residents. A flagpole erected at an unknown date stands to the northwest of the fortification.

Regarding Fort Dilts Historic Site. (Taken from Nomination Form, National Register of Historic Places, U.S. Dept. of the Interior)

In the summer of 1864, while the United States was still in the throes of civil war, emigrant wagon trains crossed the northern Great Plains to the mountains of western Montana and Idaho. Gold had been discovered in sizable quantities in those mountains, and a considerable interest in going to the gold fields had arisen in residents of the northern states and particularly in Minnesota Territory, then the westward limit of organized frontier settlement. Two routes to the gold fields were available: boat travel down the Mississippi and then up the Missouri River to Fort Benton, or overland wagon train from St. Paul to Montana. River travel was time-consuming, at times dangerous, and could be quite expensive if whole families and their belongings were to be transported.

The overland route posed problems of supply, protection, and navigation because the wagon trains would necessarily travel a distance of more than a thousand miles through territory that was virtually unmapped and unoccupied except for large numbers of Indians. The best information available on the overland route of the beginning of the 1860's were maps and notes of an 1853 exploring expedition led by Isaac Stevens, who was seeking an acceptable northern route for a transcontinental railroad. Steven's route generally ran from St. Paul northwestward across what is now central Minnesota and North Dakota to Fort Union, a fur trading post on the Missouri River, then westward along the Missouri and Milk Rivers to Fort Benton. Wagon trains successfully followed this route, and one more northerly, in 1862 and 1863 without major incident with the Indians of the region.

In the autumn of 1862, however, the Indian menace to the wagon trains and the white occupants of Minnesota increased when members of several bands of Sioux conducted wide-spread acts of hostility in what became known as the Minnesota Massacre. In the following three years major military campaigns against the Sioux were conducted by Colonel H. H. Sibley and General Alfred Sully in areas through which the wagon trains would pass. Indians in what are now central and western North Dakota who had not taken part in depredations were provoked to hostility by indiscriminate attacks by the military units.

Amid this climate of hostility and gold fever, Captain James Fisk led a wagon train out of Minnesota in

early July, 1864. Fisk had led trains over the usual Stevens route in 1862 and 1863 after being appointed military superintendent of emigration on that route. The 1864 train was very late in making its start westward, and Fisk determined that the train would take a more direct westerly route. The train left Fort Ridgeley and traveled along the Minnesota River and overland to Fort Rice on the Missouri River in what is now south-central North Dakota. Fort Rice was then under construction and was serving as the base camp for the Sully campaign of that year. Fisk discovered that the main Sully force had departed to the northwest toward the Little Missouri River Badlands about three weeks before the Fisk train arrived at Fort Rice.

After obtaining a military escort of fifty men, Fisk departed Fort Rice and followed Sully's trail along the Cannonball River for about 80 miles. At a point where Sully had turned his troops northward to intercept a band of Indians, Fisk turned the train to the south and west on a course that he hoped would skirt to the south of the dreaded badlands and shorten the distance to the mouth of the Bighorn River.

On September 2, 1864, ten days after Fisk left Sully's trail, the train was attacked by a party of Hunkpapa Sioux near Deep Creek in what is now Slope County, North Dakota. Two trailing wagons were cut off by the Indians and, although the military escort repulsed the attack, nine whites were killed and three more were seriously wounded. After a sleepless night the train broke camp and continued westward, leaving a loaf of strychnine-soaked bread at the campsite. The Sioux, who were on a hunting expedition and who later demanded a ransom of food for release of the train, found and devoured the bread. Some days later a scout for the train reported having found the bodies of several Indians, which had been partially eaten by wolves.

The wagon train continued westward for two days under continuous attack by a growing Indian force until September fourth, when the wagons were formed into a corral on a commanding ridge top. Within the day a six and one-half foot high wall of earth and sod was built around the circled wagons. The Indian attacks continued unabated for several days, and three more men died and were interred under the walls of the fortification. Among the dead was Corporal Jefferson Dilts, a scout for whom the location was named. A contingent of ten men left the fort during the night of September 4-5 to summon aid from Fort Rice.

The Hunkpapa Sioux, who had skirmished with Sully's force at least twice in the previous weeks, continued their attacks for several days and then offered to parlay the freedom of the train for food and other goods. The Indians also offered to release a white

Photographed By Cindy Bullard, June 20, 2010

6. Headstones of Five Other Soldiers Killed During the Siege

William H. Chase, Co. D, Brackett's Minn. Cav.

Theodore Rosch, Co. K, 8 Minn. Inf.

Joseph DeLany, Co. I, 8 Minn. Inf.

Augustine Carpenter, Co. G, 8 Minn. Inf.

Ernest Hoffinaster, C0. A, Brackett's Minn. Cav.

After sixteen days of confinement in the fortification, the Fisk train was rescued by a detachment from Fort Rice. Although Fisk and some of the emigrants wished to proceed westward, the train was refused further military escort in that direction. The train then returned to Fort Rice without further harassment by Indians and was disbanded.

The fortification area of Fort Dilts has not been disturbed since 1864, except for placement of military headstones for the soldiers buried under the wall. The site retains its unbroken vistas and the feeling of vastness or desolation that greeted the emigrants of the Fisk wagon train. Fort Dilts may be the only site of a classic Indian attack on a wagon train crossing the Great Plains which retains visible evidence of the incident and which remains virtually unaltered since the attack.

Also see . . . Fort Dilts State Historic Site. Fort Dilts appears today much as it did more than one hundred years ago in its pristine setting eight miles northwest of Rhame, Bowman County. (Submitted on July 18, 2010, by David Bullard of Seneca, South Carolina.)

Additional commentary.

1. Thank you

Thank you to the individual who posted all this information. I do local history research (http://56755.blogspot.com) and recently found out that Captain James L. Fiske later was the first mayor of my town, St. Vincent, MN in the 1880's. Little did I know what a fascinating life he had led before ... Learning of the military roads and Emigrant Overland Escort Service he worked with, among many other details, is what makes these people become more than names and dates. Thank you, thank you, thank you!

— Submitted August 1, 2010, by Trish Lewis of Thief River Falls, Minnesota.

2. John Thompson and the 30th WIS

Hello, It was great to find this site and marker information. I am a 4th great grand son of John Thompson, a Civil War soldier of the 30th WIS who was one of the soldiers who came to the aid of Fisk's wagon train.

John Thompson was the 1st position Corporal of Company H of the 30th Wisconsin. One of the companies that Col. D. Dill brought from Fort Rice to rescue this group. Thank you for all of this great information.

Paul Jankowski

Mountain House California

— Submitted May 22, 2012, by Paul M Jankowski of Mountain House, California.

Credits. This page was last revised on September 18, 2020. It was originally submitted on July 18, 2010, by David Bullard of Seneca, South Carolina. This page has been viewed 3,310 times since then and 73 times this year. Last updated on August 2, 2010, by William J. Toman of Green Lake, Wisconsin. Photos: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. submitted on July 18, 2010, by David Bullard of Seneca, South Carolina. • Kevin W. was the editor who published this page.