Sabino Canyon Recreation Area near Tucson in Pima County, Arizona — The American Mountains (Southwest)

Catalina Federal Honor Camp

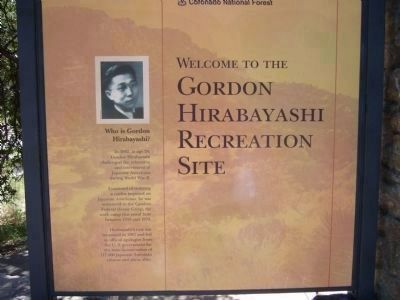

Gordon Hirabayashi Recreation Site

Inscription.

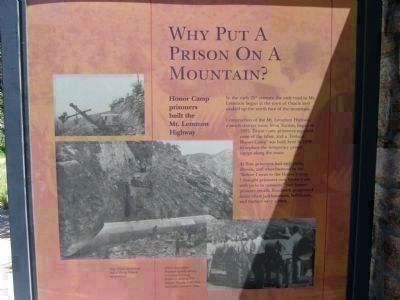

Why Put A Prison On A Mountain?

Honor Camp prisoners built the Mt. Lemmon Highway

In the early 20th century, the only road to Mt. Lemmon began at the town of Oracle and snaked up the north face of the mountain.

Construction of the Mt. Lemmon Highway, a much shorter route from Tucson, began in 1933. To cut cost, prisoners supplied most of the labor, and a "Federal Honor Camp" was built here in 1939 to replace the temporary prison camps along the route.

At first, prisoners had only picks, shovels, and wheelbarrows to use. "Before I went to the Honor Camp, I thought prisoners only broke rocks with picks in cartoons," one former prisoner recalls. Roadwork progressed faster when jackhammers, bulldozers, and tractors were added.

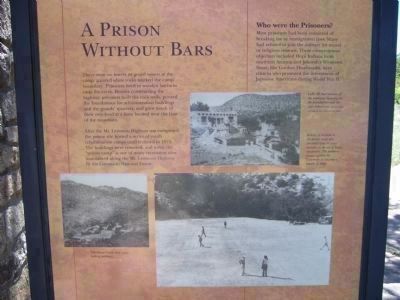

A Prison Without Bars

There were no fences or guard towers at the camp: painted white rocks marked the camp boundary. Prisoners lived in wooden barracks near the creek. Besides constructing the highway, prisoners built the rock walls, poured the foundations for administration buildings and the guards' quarters, and grew much of their own food at a farm located near the base of the mountain.

After the Mt. Lemmon Highway was completed, the prison site hosted a series of youth rehabilitation camps until it closed in 1973. The buildings were removed, and today the "prison camp" is one of many recreation sites maintained along the Mt. Lemmon Highway by the Coronado National Forest.

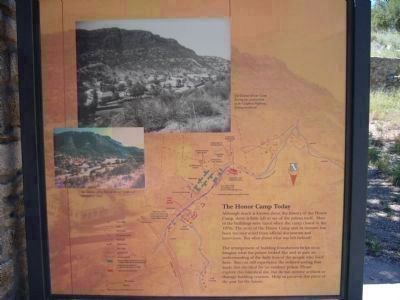

The Honor Camp Today

Although much is known about the history of the Honor Camp, there is little left to see of the prison itself. Most of the buildings were razed when the camp closed in the 1970's. The story of the Honor Camp and its inmates has been reconstructed from official documents and interviews. But what about what was left behind?

The arrangement of building foundations helps us to imagine what the prison looked like and to gain an understanding of the daily lives of the people who lived here. You can still experience the isolated setting that made this site ideal for an outdoor prison. Please explore this historical site, but do not remove artifacts of damage building remains. Help us preserve this piece of the past for the future.

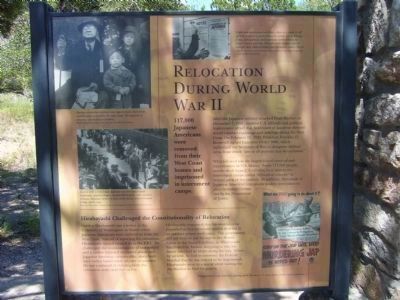

Relocation During World War II

117,000 Japanese Americans were removed from their West Coast homes and imprisoned in internment camps.

After the Japanese military attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, nervous U.S. officials and political leaders were afraid that Americans of Japanese descent would conduct espionage and sabotage along the West Coast. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive

Order 9066, which authorized the Secretary of War to designate military areas from which "any or all persons may be excluded."

What followed was the largest forced removal and incarceration in U.S. history. Some 117,000 people, two-thirds of them U.S citizens, were sent to ten internment camps, called "relocation centers," in remote parts of the country. In addition, thousands of Japanese American community leaders were taken to alien detention centers run by the Department of Justice.

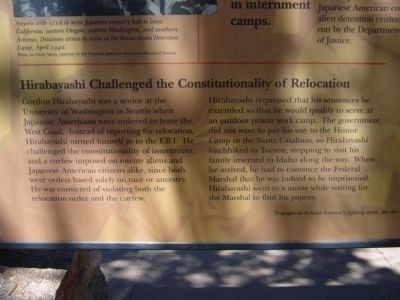

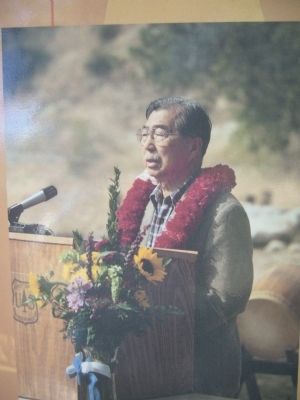

Hirabayashi Challenged the Constitutionality of Relocation

Gordon Hirabayashi was a senior at the University of Washington in Seattle when Japanese Americans were ordered to leave the West Coast. Instead of reporting for relocation, Hirabayashi turned himself in to the F.B.I. He challenged the constitutionality of internment and a curfew imposed on enemy aliens and Japanese American citizens alike, since both were orders based solely on race or ancestry. He was convicted of violating both the relocation order and the curfew.

Hirabayashi requested that his sentence be extended so that he would qualify to serve at an outdoor prison work camp. The government did not want to pay his way to the Honor Camp in Santa Catalinas, so Hirabayashi hitchhiked to Tucson, stopping to visit his family interned in Idaho along the way. When he arrived, he had to convince the

Photographed By Bill Kirchner, August 18, 2010

3. A Prison without Bars

Photo Captions:

Far Left: The Honor Camp, circa 1945, looking northeast.

Upper Photo: All that remains of the employees' housing are the foundations and the steps behind you. Photo, 1944

courtesy of the National Archives

Lower Photo: A ballfield at the prison camp also provided space to train inmates in the use of heavy equipment. The prisoners played against the University of Arizona - always at home.

Far Left: The Honor Camp, circa 1945, looking northeast.

Upper Photo: All that remains of the employees' housing are the foundations and the steps behind you. Photo, 1944

courtesy of the National Archives

Lower Photo: A ballfield at the prison camp also provided space to train inmates in the use of heavy equipment. The prisoners played against the University of Arizona - always at home.

Who is Gordon Hirabayashi?

In 1942, at age 24, Gordon Hirabayashi challenged the relocation and internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

Convicted of violating a curfew imposed on Japanese Americans, he was sentenced to the Catalina Federal Honor Camp, the work camp that stood here between 1939 and 1973.

Hirabayashi's case was reopened in 1987 and led to official apologies from the U.S. government for the mass incarceration of 117,000 Japanese American citizens and aliens alike.

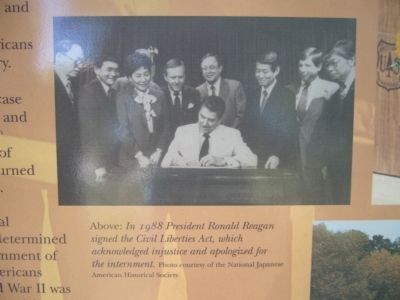

Righting a Wrong

Forty years after Hirabayashi's original conviction, law historian Peter Irons discovered documents showing that the Justice Department had withheld evidence that the forced removal and internment of Japanese Americans was unnecessary.

Hirabayashi's case was reopened, and in 1987, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals overturned his conviction.

Later, a federal commission determined that the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II was motivated by racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and failed political leadership.

Erected by Coronado National Forest.

Topics and series. This historical marker is listed in

Photographed By Bill Kirchner, August 18, 2010

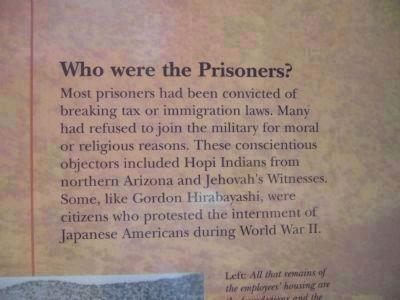

4. Who were the Prisoners?

Most prisoners had been convicted of breaking tax or immigration laws. Many had refused to join the military for moral or religious reasons. These conscientious objectors included Hope Indians from northern Arizona and Jehovah's Witnesses. Some, like Gordon Hirabayashi, were citizens who protested the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II

Location. 32° 20.35′ N, 110° 43.083′ W. Marker is near Tucson, Arizona, in Pima County. It is in the Sabino Canyon Recreation Area. Marker can be reached from Mount Lemmon Highway. Marker is in the Gordon Hirabayashi Recreation Site at mile 7.3 on the Mount Lemmon Highway. Park at the first parking area on the right and then walk about 100 feet west to the first foot bridge. Marker is just across the bridge. Touch for map. Marker is in this post office area: Tucson AZ 85749, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within 10 miles of this marker, measured as the crow flies. Honorable Frank Harris Hitchcock (approx. 2 miles away); Agua Caliente Ranch and Hot Springs (approx. 4.1 miles away); The San Pedro River Valley (approx. 4˝ miles away); Officer Erik Hite (approx. 7 miles away); Lemmon Rock Lookout Tower (approx. 7.8 miles away); Hacienda Moltacqua (approx. 9 miles away); Where Have All the Saguaros Gone? (approx. 9.8 miles away); Airmen Memorial Bridge (approx. 9.9 miles away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Tucson.

Regarding Catalina Federal Honor Camp.

Photographed By Bill Kirchner, August 18, 2010

5. The Honor Camp Today

Photo Captions:

Upper Photo: The Federal Honor Camp during the construction of the Catalina Highway, looking southwest.

Lower Photo: The remains of the Federal Honor Camp as it appeared in 1999.

Seen on the marker is a site map of the honor farm; its buildings and recreation areas.

Upper Photo: The Federal Honor Camp during the construction of the Catalina Highway, looking southwest.

Lower Photo: The remains of the Federal Honor Camp as it appeared in 1999.

Seen on the marker is a site map of the honor farm; its buildings and recreation areas.

Additional commentary.

1. Memories of the camp

If I remember right, photo #6 shows the winding stairs that were in front of the warden's house. We played there a lot. I lived in the top house in upper camp, past that was the mountain side, old ore mine shafts and bunkers. Every day the kids from upper camp would walk a trail along the creek to lower camp and ride a bus into Tucson to school. I went to Lizzy Brown Elementary. On weekends we went into Tucson and my brothers and I would be batboys for the detainees' team. My dad worked in the power house. Also I have a few pictures of staff housing and I think my sister might have some pics from lower camp. It was an adventurous time in our lives.

Editor's note: Thank you! Please feel free to add photos or other historic information to the page.

— Submitted February 2, 2024, by Judson B Jones of Billings, Missouri.

Additional keywords. Japanese American Internment - World War II

Photographed By Bill Kirchner, August 18, 2010

9. Relocation During World War II

Photo captions:

Upper left photo: During evacuation internees wore name tags to ensure that family members were assigned to the same camp. The majority of internees were elderly or children.

Photo by Dororbea Lange, 1942, courtesy of the Bancroft Library

Upper right photo: People were given anywhere from 3 days to 2 weeks to sell off their property or find someone to watch over it. Homes, farms, fishing boats, and businesses worth billions in today's dollars were lost, through under-valued sales or outright theft. Here a soldier posts Exclusion orders, March 1942.

Photo from the National Archives, courtesy of the National Japanese American Historical Society.

Lower left photo: Anyone with 1/16 or more Japanese ancestry had to leave California, western Oregon, western Washington, and southern Arizona. Detainees arrive by train at the Santa Anita Detention Camp, April 1942

Photo by Glenn Abers, courtesy of the National Japanese American Historical Society

Lower right photo: Propaganda to boast American's fighting spirit, like this U.S. Army poster, fueled racial prejudices

Upper left photo: During evacuation internees wore name tags to ensure that family members were assigned to the same camp. The majority of internees were elderly or children.

Photo by Dororbea Lange, 1942, courtesy of the Bancroft Library

Upper right photo: People were given anywhere from 3 days to 2 weeks to sell off their property or find someone to watch over it. Homes, farms, fishing boats, and businesses worth billions in today's dollars were lost, through under-valued sales or outright theft. Here a soldier posts Exclusion orders, March 1942.

Photo from the National Archives, courtesy of the National Japanese American Historical Society.

Lower left photo: Anyone with 1/16 or more Japanese ancestry had to leave California, western Oregon, western Washington, and southern Arizona. Detainees arrive by train at the Santa Anita Detention Camp, April 1942

Photo by Glenn Abers, courtesy of the National Japanese American Historical Society

Lower right photo: Propaganda to boast American's fighting spirit, like this U.S. Army poster, fueled racial prejudices

Credits. This page was last revised on February 25, 2024. It was originally submitted on August 19, 2010, by Bill Kirchner of Tucson, Arizona. This page has been viewed 3,753 times since then and 202 times this year. Last updated on May 6, 2015, by J. Makali Bruton of Accra, Ghana. Photos: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15. submitted on August 19, 2010, by Bill Kirchner of Tucson, Arizona. • Andrew Ruppenstein was the editor who published this page.