Crestwood in St. Louis County, Missouri — The American Midwest (Upper Plains)

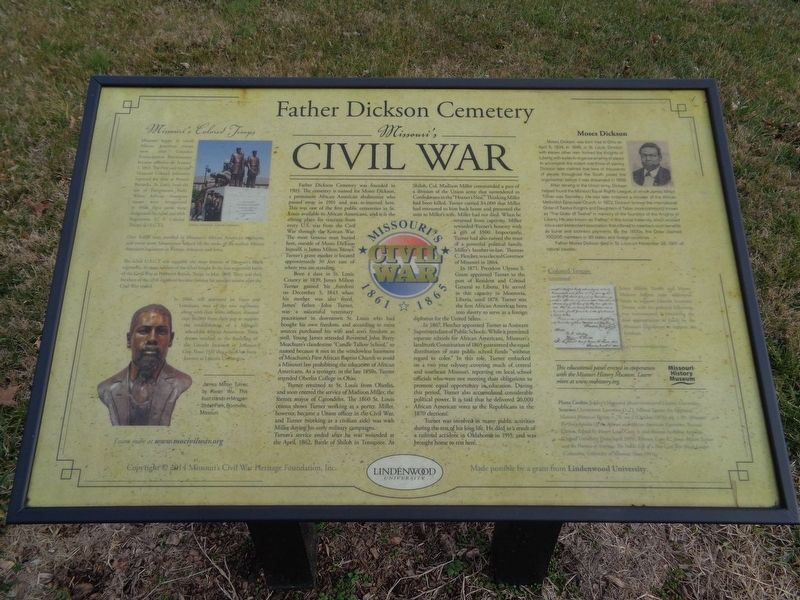

Father Dickson Cemetery

Missouri's Civil War

Born a slave in St. Louis County in 1839, James Milton Turner gained his freedom on December 5, 1843 when his mother was also freed. James' father, John Turner, was a successful veterinary practitioner in downtown St. Louis who had bought his own freedom, and according to most sources purchased his wife and son's freedom as well. Young James attended Reverend John Berry Meachum's clandestine "Candle Tallow School," so named because it met in the windowless basement of Meachum's First African Baptist Church to avoid a Missouri law prohibiting the education of African Americans. As a teenager, in the late 1850s, Turner attended Oberlin College in Ohio.

Turner returned to St. Louis from Oberlin, and soon entered the service of Madison Miller, the former mayor of Carondelet. The 1860 St. Louis census shows Turner working as a porter. Miller, however, became a Union officer in the Civil War, and Turner (working as a civilian aide) was with Miller during his early military campaigns.

Turner's service ended after he was wounded at the April, 1862, Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee. At Shiloh, Col. Madison Miller commanded a part of the division of the Union army that surrendered to Confederates in the "Hornet's Nest." Thinking Miller had been killed, Turner carried $4,000 that Miller had entrusted to him back home and presented the sum to Miller's wife. Miller had not died. When he returned from captivity, Miller rewarded Turner's honesty with a gift of $500. Importantly, Turner had also earned the trust of a powerful political family. Miller's brother-in-law, Thomas C. Fletcher, was elected Governor of Missouri in 1864.

In 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Turner to the post of Resident and Consul General to Liberia. He served in this capacity in Monrovia, Liberia, until 1878. Turner was the first African American born into slavery to serve as a foreign diplomat for the United States.

In 1867, Fletcher appointed Turner as Assistant Superintendent of Public Schools. While it permitted separate schools for African Americans, Missouri's landmark Constitution of 1865 guaranteed the equal distribution of state public school

funds "without regard to color." In this role, Turner embarked on a two year odyssey covering much of central and southeast Missouri, reporting on local school officials who were not meeting their obligations to promote equal opportunity in education. During this period, Turner also accumulated considerable political power. It is said that he delivered 20,000 African American votes to the Republicans in the 1870 elections.

Turner was involved in many public activities during the rest of his long life. He died as a result of a railroad accident in Oklahoma in 1915, and was brought home to rest here.

Missouri's Colored Troops

Missouri began to enroll African American troops soon after Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation became effective on January 1, 1863. The First and Second Missouri Colored Infantries reported for duty at Benton Barracks, St. Louis (now the site of Fairgrounds Park). When African American troops were reorganized in 1864, these units were designated the 62nd and 65th Regiments, U.S. Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.).

Over 8,000 men enrolled in Missouri's African American regiments, and many more Missourians helped fill the ranks of the earliest African American regiments in Kansas, Arkansas and Iowa.

The 62nd U.S.C.T. was arguably the most famous of Missouri's Black regiments, because soldiers of the 62nd fought in the last organized battle of the Civil War at Palmetto Ranch, Texas, in May, 1865. They, and their brothers of the 65th regiment became famous for another reason after the Civil War ended.

In 1866, still stationed in Texas and Louisiana, men of the two regiments, along with their white officers, donated over $6,000 from their pay to support the establishment of a Missouri school for African Americans. Their dream resulted in the founding of the Lincoln Institute in Jefferson City. Since 1921 this school has been known as Lincoln University.

James Milton Turner and Moses Dickson helped raise additional funds to support Lincoln Institute. Turner, with his political following, was instrumental in obtaining the first appropriation of funds by the Missouri Legislature to support the Institute.

Moses Dickson

Moses Dickson was born free in Ohio on April 5, 1824. In 1846, in St. Louis, Dickson with eleven other men formed the Knights of Liberty, with a plan to organize an army of slaves to accomplish the violent overthrow of slavery. Dickson later claimed that tens of thousands of people throughout the South joined this organization before it was disbanded in 1856.

After serving in the Union army, Dickson helped found the Missouri Equal Rights League, of which James Milton Turner was Secretary. He was later ordained a minister of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1872, Dickson formed the International Order of Twelve Knights and Daughters of Tabor, more commonly known as "The Order of Twelve" in memory of the founders of the Knights of Liberty. He was known as "Father" in this social fraternity, which evolved into a vast benevolent association that offered to members such benefits as burial and sickness payments. By the 1900s, the Order claimed 100,000 members in 30 states and foreign countries.

Father Moses Dickson died in St. Louis on November 28, 1901 of natural causes.

Erected 2014 by Missouri's Civil War Heritage Foundation, Lindenwood University and Missouri History Museum.

Topics and series. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: African Americans • Cemeteries & Burial Sites • Education • War, US Civil. In addition, it is included in the Historically Black Colleges and Universities, and the Missouri’s Civil War series lists. A significant historical year for this entry is 1903.

Location. 38° 34.005′ N, 90° 23.133′ W. Marker is in Crestwood, Missouri, in St. Louis County. Marker can be reached from Sappington Road. Marker is located at Father Dickson Cemetery. Touch for map. Marker is at or near this postal address: 845 Sappington Rd, Saint Louis MO 63126, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. Rev. Sir Moses Dickson (within shouting distance of this marker); Historic Father Dickson Cemetery (within shouting distance of this marker); Grant's Trail: Sappington House and Father Dickson Cemetery (approx. 0.2 miles away); The Barn Center (approx. 0.2 miles away); Thomas Sappington House (approx. ¼ mile away); Henry Christian Werth (approx. half a mile away); Veterans Memorial (approx. 0.6 miles away); Christopher & Mary Ann Hawken Home (approx. 0.8 miles away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Crestwood.

Credits. This page was last revised on December 28, 2020. It was originally submitted on December 28, 2020, by Jason Voigt of Glen Carbon, Illinois. This page has been viewed 235 times since then and 24 times this year. Photos: 1, 2. submitted on December 28, 2020, by Jason Voigt of Glen Carbon, Illinois.