Fort Story in Virginia Beach, Virginia — The American South (Mid-Atlantic)

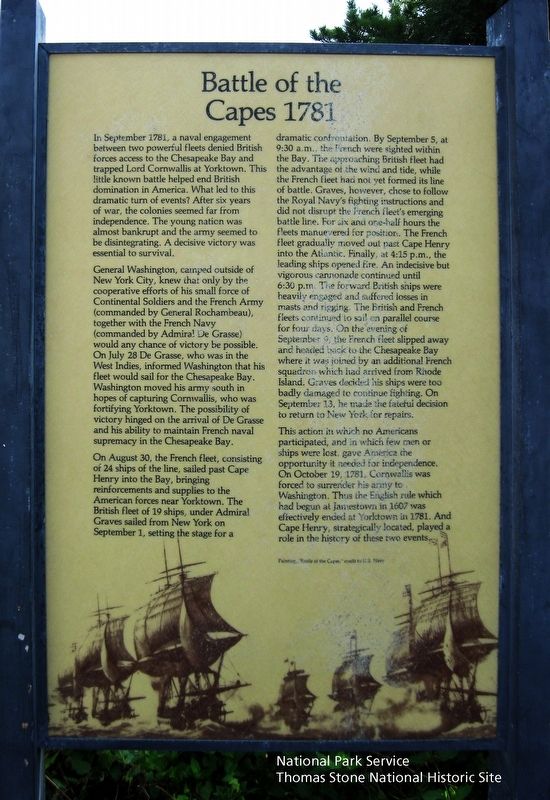

Battle of the Capes 1781

Inscription.

In September 1781, a naval engagement between two powerful fleets denied British forces access to the Chesapeake Bay and trapped Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown. This little known battle helped end British domination in America. What led to this dramatic turn of events? After six years of war, the colonies seemed far from independence. The young nation was almost bankrupt and the army seemed to be disintegrating. A decisive victory was essential to survival.

General Washington, camped outside of New York City, knew that only by the cooperative efforts of his small force of Continental Soldiers and the French Army (commanded by General Rochambeau), together with the French Navy (commanded by Admiral De Grasse) would any chance of victory be possible. On July 28 De Grasse, who was in the West Indies, informed Washington that his fleet would sail for the Chesapeake Bay. Washington moved his army south in hopes of capturing Cornwallis, who was fortifying Yorktown. The possibility of victory hinged on the arrival of De Grasse and his ability to maintain French naval supremacy in the Chesapeake Bay.

On August 30, the French fleet, consisting of 24 ships of the line, sailed past Cape Henry into the Bay, bringing reinforcements and supplies to the American forces near Yorktown. The British fleet of 19 ships, under Admiral Graves sailed from New York on September 1, setting the stage for a dramatic confrontation. By September 5, at 9:30 a.m., the French were sighted within the Bay. The approaching British fleet had the advantage of the wind and the tide, while the French had not yet formed its line of battle. Graves, however, chose to follow the Royal Navy's fighting instructions and did not disrupt the French fleet's emerging battle line. For six and one-half hours the fleets maneuvered for position. The French fleet gradually moved out past Cape Henry into the Atlantic. Finally, at 4:15 p.m., the leading ships opened fire. An indecisive but vigorous cannonade continued until 6:30 p.m. The forward British ships were heavily engaged and suffered losses in masts and rigging. The British and French fleets continued to sail on parallel course for four days. On the evening of September 9, the French fleet slipped away and headed back to the Chesapeake Bay where it was joined by an additional French squadron which had arrived from Rhode Island. Graves decided his ships were too badly damaged to continue fighting. On September 13, he made the fateful decision to return to New York for repairs.

This action in which no Americans participated, and in which few men or ships were lost, gave America the opportunity it needed for independence. On October 19, 1781, Cornwallis was forced to surrender

National Park Service, Thomas Stone National Historic Site, August 16, 2018

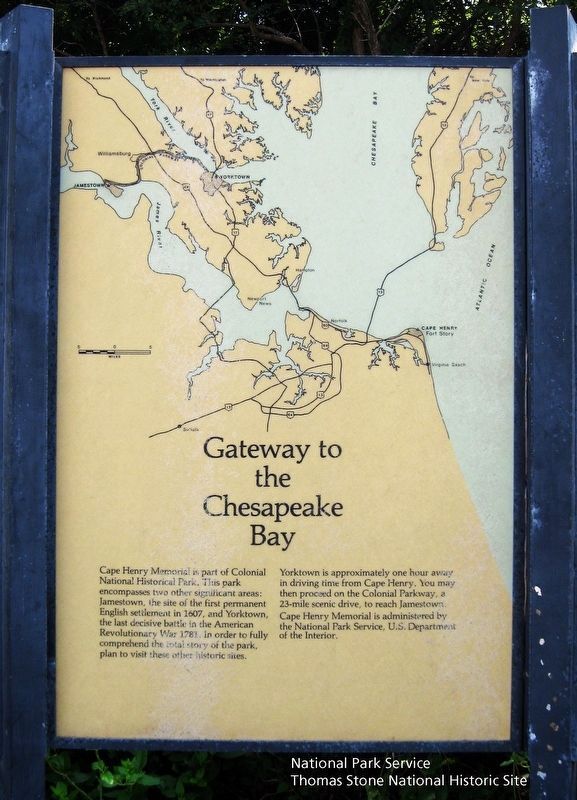

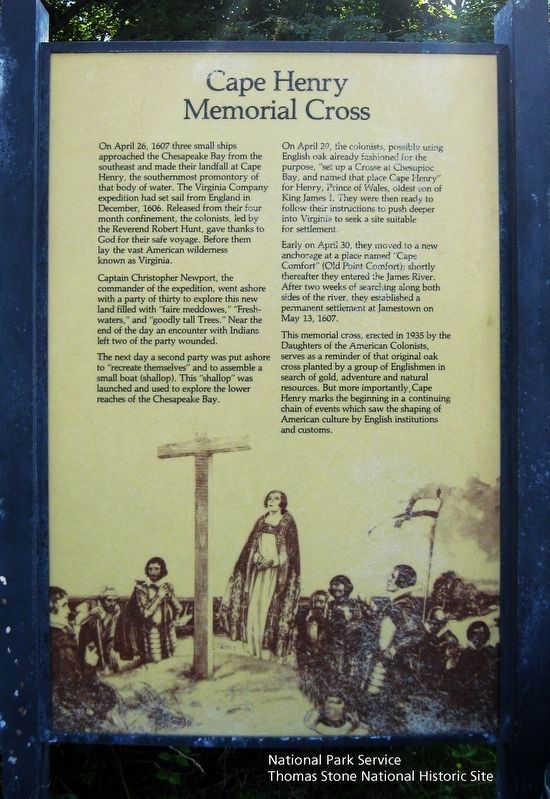

2. Battle of the Capes 1781, Gateway to the Chesapeake Bay, and Cape Henry Memorial Cross Markers.

Viewing north towards the markers. The French British Naval Engagement Off the Virginia Capes Marker is located in the background.

Painting, "Battle of the Capes," credit to U.S. Navy

Erected by National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.

Topics and series. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: Colonial Era • War, US Revolutionary • Waterways & Vessels. In addition, it is included in the Former U.S. Presidents: #01 George Washington, and the The Washington-Rochambeau Route series lists. A significant historical date for this entry is September 5, 1781.

Location. 36° 55.671′ N, 76° 0.548′ W. Marker is in Virginia Beach, Virginia. It is in Fort Story. Marker is at the intersection of Atlantic Avenue and New Guinea Road, on the right when traveling north on Atlantic Avenue. Enter the parking lot for the Cape Henry Memorial, which is maintained by the National Park Service. The marker is at the trailhead located at the northeast corner of the parking lot. Touch for map. Marker is in this post office area: Virginia Beach VA 23459, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. Cape Henry Memorial (within shouting distance of this marker); François Joseph Paul de Grasse (within shouting distance

of this marker); French British Naval Engagement Off the Virginia Capes (within shouting distance of this marker); Battle of the Capes (within shouting distance of this marker); First Landing (approx. 0.2 miles away); First Public Works Project of the United States Government (approx. 0.2 miles away); History of Cape Henry Lighthouse (approx. 0.2 miles away); British Naval Blockade and Cape Henry Lighthouse / The War of 1812 (approx. 0.2 miles away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Virginia Beach.

Also see . . .

1. Cape Henry Memorial, National Park Service. (Submitted on August 20, 2019.)

2. Washington-Rochambeau National Historic Trail, National Park Service. (Submitted on August 20, 2019.)

3. Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route Association, Inc. (Submitted on August 20, 2019.)

4. Wikipedia Entry. Excerpt:

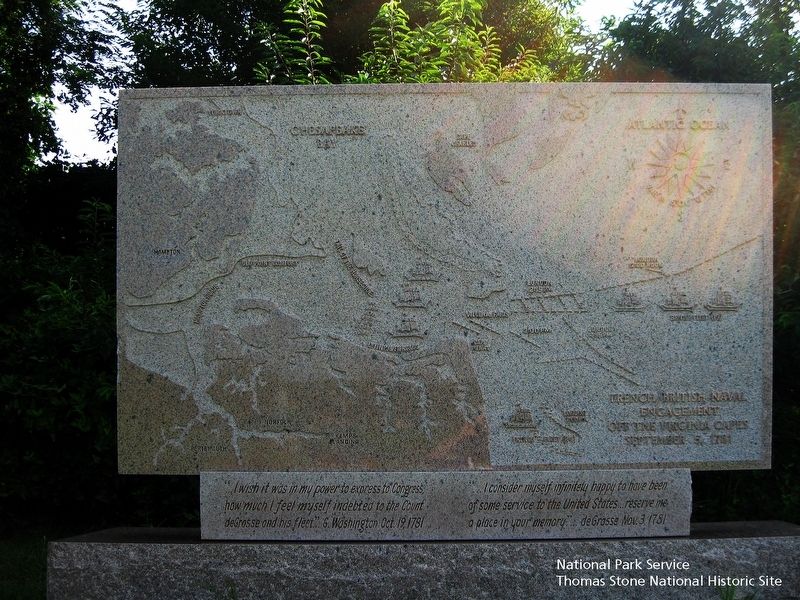

Admiral de Grasse had the option to attack British forces in either New York or Virginia; he opted for Virginia, arriving at the Chesapeake at the end of August. Admiral Graves learned that de Grasse had sailed(Submitted on August 28, 2021.)from the West Indies for North America and that French Admiral de Barras had also sailed from Newport, Rhode Island. He concluded that they were going to join forces at the Chesapeake. He sailed south from Sandy Hook, New Jersey, outside New York Harbor, with 19 ships of the line and arrived at the mouth of the Chesapeake early on 5 September to see de Grasse's fleet already at anchor in the bay. De Grasse hastily prepared most of his fleet for battle—24 ships of the line—and sailed out to meet him. The two-hour engagement took place after hours of maneuvering. The lines of the two fleets did not completely meet; only the forward and center sections fully engaged. The battle was consequently fairly evenly matched, although the British suffered more casualties and ship damage, and it broke off when the sun set. The British tactics have been a subject of debate ever since.National Park Service, Thomas Stone National Historic Site, August 16, 20184. French British Naval Engagement Off the Virginia Capes MarkerViewing north towards the marker, which is located beyond the Battle of the Capes 1781 marker. The map in this marker identifies the following geographic locations: the Atlantic Ocean, Cape Charles, Cape Henry, Chesapeake Bay, Hampton, Hampton Roads, Lynnhaven Roads, Old York Comfort, Tail of the Horseshoe, and Yorktown. Map also shows position of French and British ships and/or fleets at 12:00 noon, 2:00 pm, 2:15 pm, 4:15 pm, and 7:00 pm.

The two fleets sailed within view of each other for several days, but de Grasse preferred to lure the British away from the bay where de Barras was expected to arrive carrying vital siege equipment. He broke away from the British on 13 September and returned to the Chesapeake, where de Barras had since arrived. Graves returned to New York to organize a larger relief effort; this did not sail until 19 October, two days after Cornwallis surrendered.

Credits. This page was last revised on February 1, 2023. It was originally submitted on August 20, 2019. This page has been viewed 770 times since then and 52 times this year. Last updated on March 30, 2022. Photos: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. submitted on August 20, 2019. 7. submitted on August 28, 2021, by J. J. Prats of Powell, Ohio. • Bernard Fisher was the editor who published this page.