Back of the Yards in Chicago in Cook County, Illinois — The American Midwest (Great Lakes)

Union Stock Yard

Chicago

— Est. 1865 —

The Union Stock Yard and Transit Company, Chicago's legendary livestock market and slaughterhouse, opened at this site on Christmas Day, 1865. Here, 320 acres of swampland lying between Pershing Avenue, Halsted Street, 47th Street, and Ashland Avenue were transformed into the world's largest livestock trading and meat processing center. What drew nine railroad companies to purchase and develop this site in Chicago was the city's unparalleled location in the heart of the nation's corn belt, where hog production flourished and Texas ranchers sent cattle to be fattened up for market. Its extensive railroad network linking the American West with large East Coast cities, its Board of Trade, and its sophisticated banking and credit system, provided the support needed to make Chicago the meat capital of the world.

Civil engineer Octave Chanute laid out the stockyards in a grid system of streets and alleys with 120 acres of livestock pens. Fifteen miles of internal railroad tracks linked the site to the city's main railroad lines, and thirty miles of sewers and drains emptied animal waste directly into a fork in the south branch of the Chicago River that came to be known as "Bubbly Creek." Animals could be unloaded directly from railcars, driven through this gate and herded into pens to await trade or slaughter.

Livestock receipt tallies reflect the instant and astronomical success of the stockyards. In 1866, the first year of operation, the yards received 1,286,326 hogs and 384,251 cattle. Despite the devastation caused in other parts of the city by the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, business at the stockyards never slowed. In the decades following the fire, hog receipts jumped 137%, cattle 422%, and sheep 591%. Not just livestock trading, but especially meatpacking, which had been initiated here shortly after the yards opened, also grew phenomenally. The dollar value of processed meat products expanded 900% in twenty years.

Immediately inside this massive stone gate was a sea of crowded pens that could hold over 100,000 head of livestock. In the midst of them was the Exchange Building, with offices for the livestock traders. Beyond the pens, "Packingtown" emerged in the half-mile-square area west of Racine Avenue, where all manner of meat processing, packaging, and preserving operations occurred in eight- to ten-story brick buildings. Just outside the gate were the Live Stock National Bank (still standing at Halsted Street and Exchange Avenue), a Transit House with hotel accommodations, and later the Stockyards Inn and the International Amphitheatre, once one of the largest convention and exhibition halls in the nation.

Chicago's Union Stock Yard attracted men of courage and bold vision. The "Big Three" of the meatpacking industry — Nelson Morris, Philip D. Armour, and Gustavus Swift — all operated meat dressing and packing plants at this site. Morris arrived in Chicago and opened his own business in 1859. He and a branch of Armour & Company of Milwaukee were among the first to locate at the stockyards in 1867. By 1875, pork baron Philip Armour himself, had moved to and relocated his headquarters in Chicago. Swift came from Boston at about the same time and was shipping dressed beef back to Boston by 1877. For the tremendous amount of waste being generated, factories were built to refine fats and oils, to tan leather, and to manufacture soap, glue, dye, fertilizer, buttons, and violin strings. As the saying went, "everything of the pig was used except the squeal."

Important technological advances continually improved the speed of production and the quality of products. The disassembly process for hogs first pioneered at the stockyards became the forerunner of industrial mass production techniques used by Henry Ford and others in the 20th century. In 1866, Windsor Leland created a machine known as the hog wheel in which a steam-powered wheel connected to an overhead rail lifted and moved hog carcasses down a line where each worker performed a single operation. This process enabled a butcher to split and cut nine hogs in three minutes. Different

Photographed By Sean Flynn, April 2, 2024

3. Union Stock Yard Gate

The marker can be seen just to the left of the gate in this photo. The Chicago Landmark marker is in the right corner of the photo, and the Fallen 21 statue can be seen in the rear beyond the gate. Above the gate the carving of the bull "Sherman" is visible.

The development of a means of shipping refrigerated meats allowed the slaughtering, processing, and packaging of dressed meats to be done at this centralized location. Before experimentation with ice-cooled boxcars began in 1872, frozen meats could only be shipped during the coldest winter months. The refrigerated railroad car developed and built by Gustavus Swift in 1882 revolutionized the industry.

Chicago's Union Stock Yard operated over 105 years with its peak years of production between 1918 and 1924. The Great Depression and a sweeping fire in 1934 initiated its demise, but it was the rapid growth of the federal highway system that eventually led to the closing of the Chicago stockyards. The use of refrigerated trucks eliminated the need for central rail access, enabling meatpackers to build new facilities in cheaper, rural locations. By the late 1950s many of the meatpacking companies such as Swift, Armour, and Wilson had begun relocating their general offices out of the stockyards, and they gradually stopped slaughtering and processing operations. For another ten years the sale, trading and shipping of meat continued to provide some jobs. But on August 1, 1971, all operations ceased at the Union Stock Yard. The area has been since been redeveloped as an industrial

park, which today has 200 firms employing 17,000 workers.

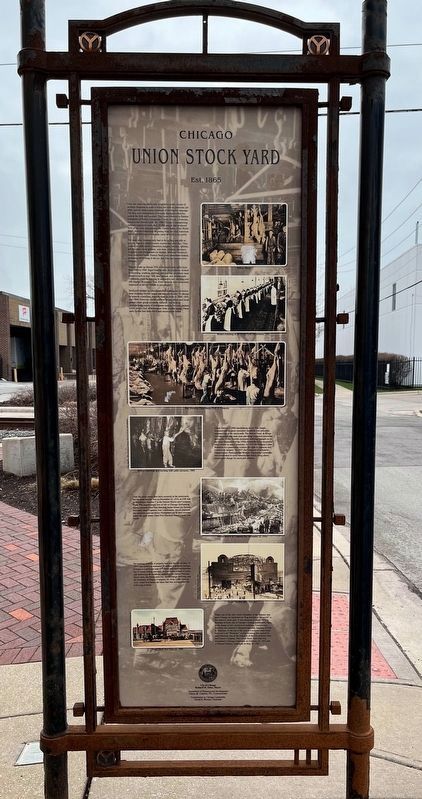

[Rear of the marker:]

Over the years the stockyards attracted a steady stream of workers desperate to make a living but with no particular job skills, and for some a poor command of the English language. The first were immigrants of western European ethnicity, such as the Irish and Germans. They were followed by Eastern Europeans of Polish, Lithuanian, Czech, Slovak, Ukrainian, Russian and Jewish stock. By 1900 Chicago's meatpacking industry employed more than 25,000 people and produced 82% of the meat consumed in the United States. After World War 1, African-Americans migrating from the rural American South and Mexican immigrants came to work in the yards.

For most jobs, workers only had to be willing and able to quickly repeat a simple routine motion day after day. They worked as cattle drivers, shacklers, hangers, hoisters, splitters, gut throwers, neck splitters, vein tiers, washers, trimmers, weighers, and refrigerated car loaders. Working conditions were extremely harsh. Factory floors were often blood-soaked, sickening odors hung in the air, and flies and vermin were rampant.

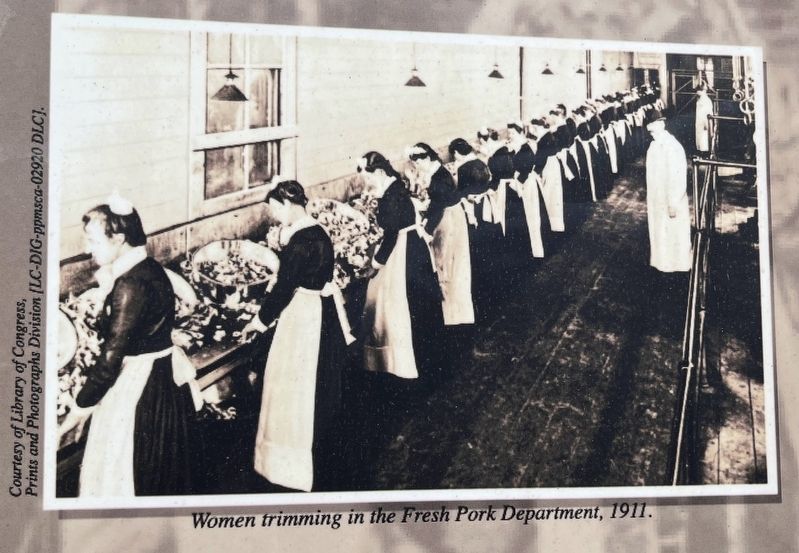

Women made up almost 15% of the stockyards labor force from 1900 to 1940. Supervised by men, they typically worked in trimming, washing, packing, and pickling secondary meat products such as pigs' feet, beef

tongue, and sweetbreads. Conditions could be freezing or unbearably hot, reaching over 100 degrees in summer heat. Even children were sometimes employed at the stockyards as messengers.

Stockyard laborers became dissatisfied working ten- to twelve-hour workdays for low wages and little job security. To attempt to improve conditions, workers went on strike in 1886, 1894, and 1904. However, social conflicts among ethnic and racial groups made group solidarity difficult. And with an overwhelming supply of immigrants looking for work, packers could always find strikebreakers from another group. These early strikes had little effect and unionization failed.

Upton Sinclair's 1906 muckraking novel, The Jungle, immortalized the poor sanitation standards and unhealthy surroundings at the stockyards. The federal Food & Drugs Act was passed that same year, and things improved somewhat during the 1920s. Terrible economic suffering brought on by the Great Depression of the 1930s eventually led to successful labor reform in many industries. In 1935 the National Labor Relations Act guaranteed workers the right to organize and collectively bargain. In 1937, the Congress of Industrial Organizations' Packinghouse Workers Organizing Committee was established to unify laborers and finally bring about meaningful change for stockyard workers.

Over the years many fires

have occurred at the stockyards, but the most horrific was on December 22, 1910, at 4:09 AM in Warehouse Number 7 at the Nelson Morris and Company Plant. The largest single loss of life in Chicago firefighting history claimed Chief Fire Marshall James Horan, his Second Assistant, three Captains, four Lieutenants, eleven pipemen and truckmen, and one driver. Firefighters can be seen crowded below the spot where Chief Fire Marshall Horan's body was found.

Devastating in terms of property loss was the fire on May 19, 1934, that caused an estimated $8 million in property damage. It began in a stock pen near 45th Street and raged uncontrolled for six hours, killing one man, several hundred head of cattle, and destroying 40 buildings, including the Dexter Pavilion shown here, the Stockyards Inn, the Exchange Building, and the firehouse of Engine Company 59. Over 2,000 firemen were called in to battle the blaze that was extinguished the following evening.

Today one of the only visual reminders of the industry that gave Chicago its reputation as "hog butcher of the world" is this massive stone gate. It was designed in about 1875 by Burnham & Root, one of Chicago's leading architectural firms in the design of tall commercial buildings. Lead partner Burnham was married to Margaret Sherman, daughter of John B. Sherman. At the top of the arch is a sculpted cattle head, believed to be "Sherman," a prize-winning bull named for John Sherman, one of the founders of the Union Stock Yard and Transit Company. The Union Stock Yard Gate was designated a Chicago Landmark on February 24, 1972 and a National Historic Landmark on May 29, 1981.

Erected by Department of Planning and Development; Commission on Chicago Landmarks; City of Chicago.

Topics. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: Agriculture • Immigration • Industry & Commerce • Labor Unions. A significant historical year for this entry is 1865.

Location. 41° 49.113′ N, 87° 38.911′ W. Marker is in Chicago, Illinois, in Cook County. It is in Back of the Yards. Marker is on West Exchange Avenue east of South Peoria Street, on the left when traveling east. The marker is next to the Stock Yard Gate, immediately to its south. Touch for map. Marker is in this post office area: Chicago IL 60609, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within one mile of this marker, measured as the crow flies. The Fallen 21 (a few steps from this marker); Leslie F. Orear (a few steps from this marker); Union Stock Yard Gate (a few steps from this marker); People of Canaryville (approx. 0.2 miles away); Lt. Joseph T. (Jay) McKeon Jr. Park (approx. 0.8 miles away); Andrew "Rube" Foster (approx. 0.9 miles away); Bridgeport and the Development of Chicago's Infrastructure (approx. one mile away); Carlton Fisk (approx. 1.1 miles away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Chicago.

More about this marker. This marker features a variety of historical photos of the stockyards and some of the incidents referenced in the text. The marker, held up on wrought iron, matches the style seen in some other markers around Chicago, including one about ¼ mile northeast of here on Halsted Street (celebrating the Canaryville and Bridgeport neighborhoods) and a series of markers in the Loop on Dearborn and State streets. While there is no date on this marker, it was likely erected in the early 2000s.

An official Chicago Landmark marker can be found a short walk northeast of here, on a concrete slab. On the Stock Yard Gate itself, on the inside of the arch, is also a marker describing the "Fallen 21" Chicago firefighters who died in the fire of December 22, 1910. To the west is a statue dedicated to those fireman, which also lists all of the more than 530 Chicago firefighters who have died in the line of duty since 1865.

Also see . . .

1. WTTW-TV (Channel 11, Chicago): The Union Stockyards: A Story of American Capitalism. (Submitted on April 3, 2024, by Sean Flynn of Oak Park, Illinois.)

2. The People of the Stock Yards. From Chicago's Packingtown Museum (Submitted on April 3, 2024, by Sean Flynn of Oak Park, Illinois.)

Credits. This page was last revised on April 3, 2024. It was originally submitted on April 2, 2024, by Sean Flynn of Oak Park, Illinois. This page has been viewed 65 times since then. Photos: 1, 2, 3. submitted on April 2, 2024, by Sean Flynn of Oak Park, Illinois. 4, 5, 6. submitted on April 3, 2024, by Sean Flynn of Oak Park, Illinois.