Tecpán Guatemala, Chimaltenango, Guatemala — Central America

The Sociopolitical Organization of Mayan Social Classes

Inscription.

Este marcador está hecho de cinco paneles bajo un techo.

Los Reyes y los nobles trataban los asuntos políticos y militares de la sociedad, muy importantes en la época bélica de finales del siglo XV. Los sacerdotes, procedentes de esta clase social, controlaban el aspecto religioso y sus manifestaciones. Los nobles se encargaban finalmente de cobrar los tributos a los vasallos y de controlar el flujo de los intercambios a larga distancia. Reyes y nobles vivían en el centro de Iximché.

Sobre el origen de los Señores, los relatos Kaqchikeles hablan de la llegada de grupos “mexicanizados” procedentes de Tula, alrededor del año 1200 d.C. Estos grupos de mayas-mexicanizados se casaron con los miembros de los grupos gobernantes locales, originando así las clases gobernantes de las futuras naciones K’iches, Kaqchikeles y Tz'utujiles. La evidencia arqueológica confirma este contacto con poblaciones y tradiciones mexicanas, y la adopción por las elites locales de numerosos rasgos culturales originarios de México.

Los Anales mencionan que dos Señores o Reyes ejercían el poder antes de la conquista. Su cargo era hereditario y sus títulos eran Ahpoxahil y Ahpozotzil. Debajo de ellos, existían también nobles de importancia un poco menor: los Ahpopcamhay y Ahpop Achi. A todos los Señores y miembros de la alta nobleza, se les llamaban en las fuentes ajawab traducido como “señor, dueño, jefe, cacique” en los diccionarios. Mientras que al estrato más bajo de la nobleza, se aplicaba el termino de ac'animak, “pariente de noble”, traducido también en los diccionarios como “noble por familia” o “principales o autoridad”.

Los dos Señores de lximché vivían en el centro de la ciudad. Se supone que ocupaban, con su Corte, los llamados "Palacio 1" en la Plaza B y el “Palacio 2” en la Plaza C, mientras que otros miembros de la nobleza vivían en los edificios de la Plaza D, aún sin investigar.

La muerte de los Reyes era acompañada de grandes cambios en la ciudad. Martín Alfonso Tovilla cuenta en 1635 sobre los K'iches que "cuando moría un rey se encalaban

todas las calles y los palacios por dentro y por fuera y se pintaban nuevas historias". Es muy posible que las diferentes capas de estuco encontradas en las plazas de Iximché correspondan a prácticas análogas.

Por otra parte, los diferentes niveles de construcción superpuestos de los palacios y templos así como las sepulturas halladas en los patios, podrían indicar también que a la muerte de un Señor se le incineraba o se le enterraba en su plaza. Posteriormente, se arrasaba su morada y se volvía a construir encima un nuevo palacio o templo para el nuevo rey.

Pie de dibujos:

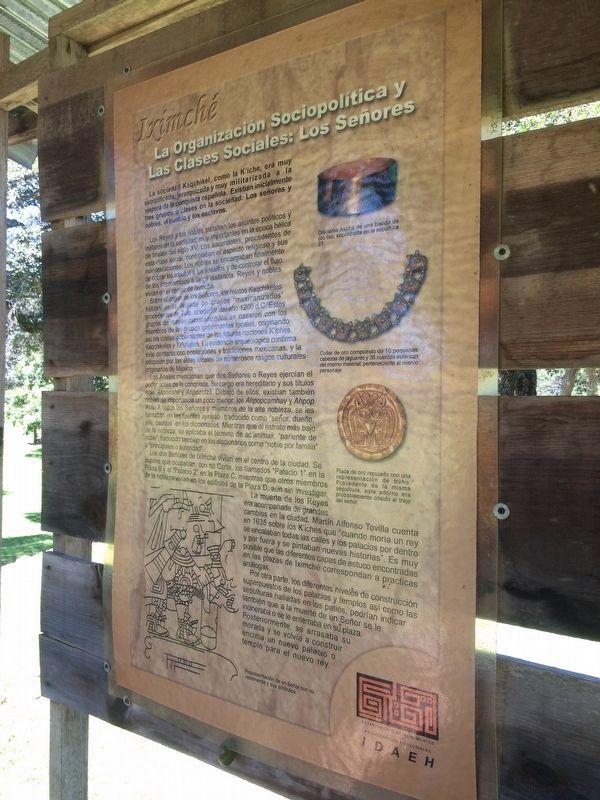

Diadema hecha de una banda de oro liso, encontrada en la sepultura 27.

Collar de oro compuesto de 10 pequeñas cabezas de jaguares y 36 cuentas esféricas del mismo material, perteneciente al mismo personaje

Placa de oro repujado con una representación de búho. Procedente de la misma sepultura, este adorno era probablemente cosido al traje del señor.

Representación de un Señor con su vestimenta y sus atributos.

mitos de la creación del mundo. La unión de los conocimientos relativos a estos diferentes grupos, permite reconstruir las grandes líneas de una religión de las Tierras Altas en la época Posclásica. La arqueología, sin embargo, provee más información acerca de las prácticas religiosas (las ceremonias) que sobre las creencias que no dejan testimonios materiales directos.

Las bases de la religión maya Posclásica se encuentran desde el Período Preclásico cuando, en todas las ciudades nacientes de la Zona Maya, las elites empezaron a construir pirámides para honrar a sus muertos, atestiguando la práctica de un culto a los ancestros que perdura mas allá de la Conquista Española. Los ancestros de los reyes mayas de la época Clásica eran divinos y es muy probable que esta creencia haya perdurado en periodos tardíos. La religión maya estaba desde sus principios, basada sobre la relación entre el hombre y el universo. Dioses y seres sobrenaturales tenían un papel muy importante, tanto en la creación del mundo (de la Naturaleza y del Hombre), como en el funcionamiento del universo (el Sol que se levanta y se pone, las lluvias para la buena cosecha).

La religión maya es politeísta (de varios dioses): las divinidades y los seres híbridos representados en la iconografía clásica son numerosos, de forma humana (antropomorfas) o animal (zoomorfas). Sus características

y sus aspectos son múltiples, complementarios y a veces opuestos y es difícil entender las creencias Clásicas únicamente a través de sus representaciones.

La religión “tardía” es más fácil entender, ya que los mayas Posclásicos de Yucatán han dejado manuscritos (los códices) con representaciones de dioses y detalles de ceremonias. Existen también los textos indígenas y españoles del momento del contacto.

Mientras que en las épocas Preclásica y Clásica se rendía culto a las fuerzas naturales, representadas por seres cambiantes, en el Posclásico, las imágenes de las divinidades se fijaron formando un panteón tardío jerarquizado. A la religión maya Clásica en al cual encontramos el culto a los ancestros, deidades solares, del inframundo, de los puntos cardinales y del centro, del sol naciente y del poniente, de las buenas cosechas. Las migraciones venidas del Altiplano Mexicano trajeron un culto a las deidades guerreras y cambios en las ceremonias con la introducción del culto a las imágenes (la idolatría) y el aumento notable del sacrificio humano, que ya existía en la Zona Maya desde el Preclásico.

Los cambios en el tiempo de las creencias y las prácticas religiosas se pueden explicar tanto por la influencia mexicana, como por el debilitamiento del poder político de la clase dominante de los diferentes grupos y el ambiento bélico de la época.

Mientras que durante el Clásico se rendía culto al soberano, representado en las estelas y descendiente de los dioses; en el Posclásico, los rituales de la elite y los sacrificios eran destinados a las divinidades guerreras.

En lo que refiere a la mitología de las Tierras Altas de Guatemala, la fuente más valiosa, aunque posterior a la conquista, es sin duda el Popol Vuh, libro sagrado de los K’iches.

Pie de dibujos:

Representación de un ser híbrido zoomorfo, en un altar de piedra de las Tierras Bajas, de la época Clásica Tardía. (Foto: R. Sibille).

La religión Posclásica: dioses y ceremonias representados en el Códice de Madrid, manuscrito Posclásico yucateco, elaborado a manera de un almanaque ritual.

Iximché, escultura de piedra fragmentada, quizás representación en piedra de una divinidad.

Representación divina en un incensario policromo de Iximché.

Se trataban tanto de Kaqchikeles comunes como de grupos conquistados. La condición de vasallo era aparentemente hereditaria, sin embargo las uniones entre vasallos y nobles no estaban totalmente excluidas.

Esta clase de la sociedad es muy poco conocida por la arqueología. Sabemos por los textos, que este grupo, regido por una ley diferente de la de los nobles, proveía

diferentes tributos a la elite gobernante, permitiéndole conservar su estatus. Aprovisionaban a la elite de alimentos, piedras y otros materiales de construcción así como de materias primas para la artesanía y objetos manufacturados, además de fabricar la ropa y armas.

Los vasallos eran también la mano de obra para la construcción de los caminos y edificios públicos y religiosos. Eran soldados en las guerras y espectadores en las ceremonias religiosas llevadas a cabo en el centro de la ciudad.

El pueblo vivía fuera del centro fortificado de Iximché, en las pendientes de la periferia y en los campos de los alrededores. Esta población estaba, al igual que los K'iches organizada en barrios - chinamit - que reunían a varios patrilineajes de vasallos sumisos a un mismo jefe, y que portaban el nombre del linaje señorial. En caso de ataque enemigo, el pueblo, como en la época medieval europea, buscaba refugio en el centro fortificado.

Los siervos y los esclavos

Todas las fuentes del Siglo XVI coinciden en que la esclavitud estuvo desarrollada tanto en las naciones Kaqchikel como K’iche. R. Carmack diferencia dos tipos de individuos serviles, a los que llama "siervos" y "esclavos".

Los siervos también llamados nimak achi - gente grande - eran probablemente miembros de etnias conquistadas, cuyos grupos enteros, incluyendo sus principales habían

sido llevados a la ciudad. Lograban una posición social relativamente privilegiada, comparable a la de los vasallos. Conservaban su idioma, formaban sus propias secciones en los barrios, pagaban tributos y servicios y participaban en las guerras. Sin embargo, tenían menos derechos y más servicios obligatorios. Conformaban colonias serviles.

Los esclavos eran los prisioneros de guerra. Los señores capturados en la guerra eran inmediatamente sacrificados, mientras que sus vasallos entraban en servidumbre antes de ser sacrificados. Llamados munil - esclavo, cautivo, preso – o winakitz - muchacho de collar – eran destinados al servicio de las casas de los señores, en las cuales vivían a la espera de ser sacrificados.

Los historiadores actuales opinan que la estructura tripartita inicial de la sociedad, se vio un tanto transformada a finales del siglo XV, con el surgimiento de una “Clase media”, procedente, o bien del pueblo, o bien, de la pequeña nobleza, y compuesta tanto por militares como por comerciantes y artesanos enriquecidos. La presencia de este grupo intermedio, hubiera quizás desestabilizado el poder de los reyes y de los nobles, creando fricciones en la sociedad. Mientras que nobles, vasallos y esclavos podía funcionar, surgieron problemas con el poder creciente de estas clases especializadas, debilitando el estado Kaqchikel a la víspera de la conquista.

Pie de dibujos:

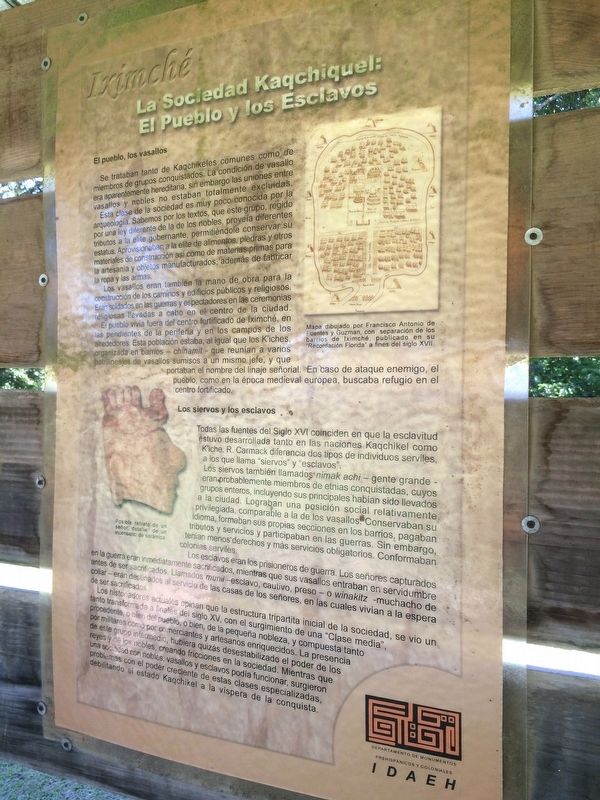

Mapa dibujado por Francisco Antonio de Fuentes y Guzman, con separación de los barrios de Iximché, publicado en su “Recordación Florida” a fines del siglo XVII.

Posible retrato de un señor, detalle de un incensario de cerámica

Las ceremonias se llevaban a cabo tanto en fechas de cambios de período, establecidos en el calendario maya, como en momentos especiales, y su desarrollo y modalidades variaban según la ocasión. La ascensión al trono de un nuevo señor, su muerte, la reparación de un templo, la preparación del ejército para la guerra o su regreso victorioso, proveían ocasiones especiales para la realización de ceremonias a fin de pedir la protección o para agradecer a las divinidades representadas por estatuas de madera o de piedra o por figurillas. Este culto fue llamado equivocadamente "idolatría" por los cronistas españoles.

Las excavaciones realizadas en los edificios de las Plazas A, B y C revelaron los vestigios de las diferentes prácticas religiosas de la elite de Iximché.

La quema de incienso

Representa en el Posclásico la actividad mayor de las ceremonias. Se quemaba el pom u otras substancias como el látex, dentro de recipientes de cerámica de formas muy variadas, en los templos, enfrente de ellos, al pie de las pirámides o caminando en procesión de un lugar a otro, en los palacios y en las casas. (Ver el panel sobre incensarios en la Plaza A).

Las “reliquias”

El hallazgo en el Templo 3, de una vasija fragmentada de tipo "Plomiza", que ya no eran producidas en el siglo XV, podría indicar que al igual que durante el Periodo Clásico en las Tierras Bajas, se conservaban algunos objetos, antiguas propiedades de los ancestros, a manera de reliquia.

La música

Un fragmento de flauta tallada en un hueso humano y varios fragmentos de ocarinas de cerámica, son los instrumentos de lximché que han perdurado hasta nuestros días.

El sacrificio de animales

Practicado desde el Período Clásico hasta hoy día, tenía en el Posclásico el propósito de alimentar a los dioses con la sangre de los animales sacrificados. El obispo Landa de Yucatán cuenta que se untaba a los “ídolos” (las estatuas de los dioses) con esta sangre. Se escogía el tipo de animal según el destinatario del ritual.

No existen en lximché vestigios directos del sacrificio de animales. Sin embargo, enfrente del Templo 2, fue hallado un bloque de piedra estucado de forma cilíndrica, de unos 40 cm de diámetro y unos 20 cm de grosor con la parte superior ligeramente cóncava, muy similar a las piedras de sacrificio aztecas y que tenía quizás el mismo uso.

Queda sin resolver hoy día la pregunta de saber si los sacrificios realizados en la piedra eran animales o humanos.

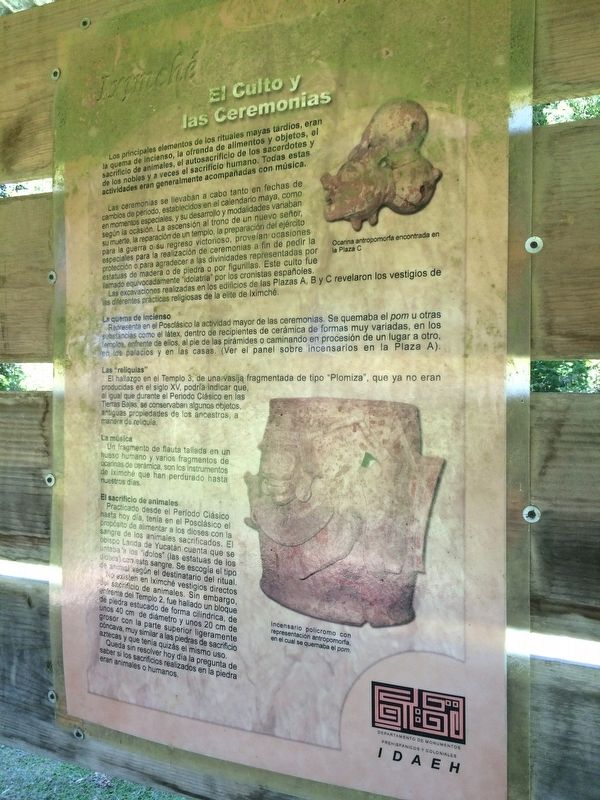

Pie de dibujos: Ocarina antropomorfa encontrada en la Plaza C

Incensario policromo con representación antropomorfa, en el cual se quemaba el pom.

Común entre los Mayas desde épocas muy remotas, se practicaba en las cuevas o en la oscuridad de los templos, era un rito tanto de purificación como para alimentar a los dioses. El autosacrificio consistía en hacerse sangrar las orejas, la lengua o el pene con un instrumento punzante o cortante de obsidiana o una aguja de mantarraya. Considerado como un acto individual de contrición, podía sin embargo realizarse colectivamente en ciertas ceremonias del Posclásico.

Se practicaba en lximché como lo atestigua un detalle de los murales del templo 2 en el cual el personaje, practica el autosacrificio perforándose la lengua.

El sacrificio humano

Presente en toda Mesoamérica posclásica, el autosacrificio humano era muy probablemente menos común que el sacrificio de animales. Si bien, el objetivo de alimentar y complacer a los dioses era el mismo, su realización parecía reservada a ocasiones especiales. Estas últimas pueden haber sido ligadas en la mayoría de los casos a la práctica del Juego de Pelota.

En Iximché, las víctimas del sacrificio eran decapitadas, después de haberles arrancado el corazón. Dos depósitos de cráneos decapitados asociados a navajillas de obsidiana, fueron hallados en la proximidad de dos pequeñas estructuras ubicadas al Sur de los templos 2 y 4 en las Plazas A y C, entre los templos y las canchas de Juego de Pelota. Los cráneos (un total de 25 individuos) conservaban las primeras vértebras cervicales, con las huellas de corte de la decapitación. Se trataba tanto de hombres como de mujeres, cuya edad oscilaba entre 15 y 25 años de edad. La representación de los dos sexos indica claramente que no se trataba de jugadores de pelota sino probablemente, de cautivos de guerra.

Guillemin identificó la pequeña estructura ubicada enfrente de la pirámide 2 a proximidad de la cual fueron hallados los cráneos, como un posible Tzompantli: el lugar donde se exponían las cabezas de los sacrificados, montadas en unas estacas de madera, y cuyos muros están, en un ejemplo de Chichen Itza, decorados con huesos largos y cráneos humanos.

La sepultura 27-A, de uno de los Señores de Iximché, atestigua otro tipo de sacrificio humano: el de los acompañantes del Señor en su viaje al Inframundo. Ahí, mientras el señor fue sepultado en posición sentada con todos sus atributos de oro, tres individuos sacrificados para la ocasión y colocados en posición flexionada en la fosa, lo acompañan en su última morada.

Pie de dibujos:

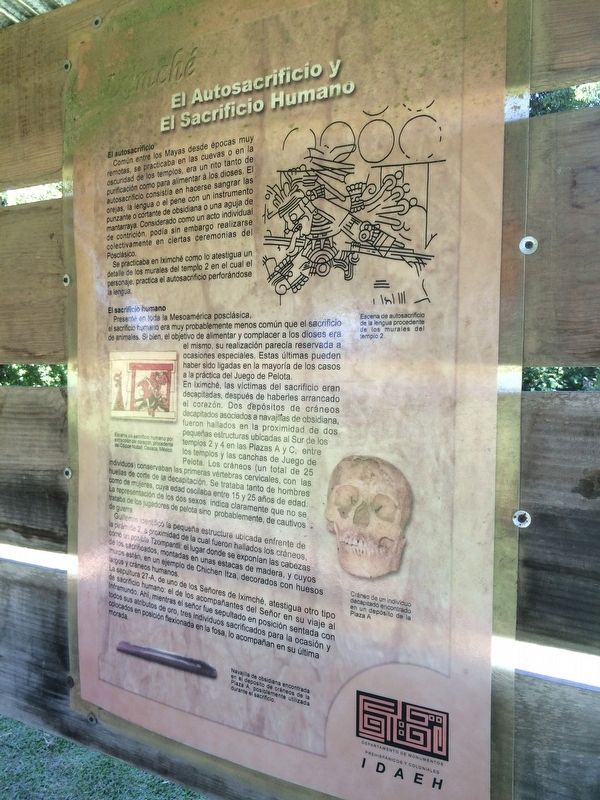

Escena de autosacrificio de la lengua procedente de los murales del templo 2.

Escena de sacrificio humano por extracción del corazón, procedente del Códice Nuttall, Oaxaca, México.

Cráneo de un individuo decapitado encontrado en un depósito de la Plaza A.

Navajilla de obsidiana encontrado en el depósito de cráneos de la Plaza A, posiblemente utilizada durante el sacrificio.

The marker is made up of five panels.

The lords and nobles managed the political and military affairs of the society, important topics in the war-plagued era of the late fifteenth century. The priests, also coming from this social class, controlled religion and its outward appearances. The nobles were in charge of collecting tributes from their vassals and of controlling the flow of long distance commerce. The lords and nobles lived in the center of Iximché.

On the origin of the lords, the Kaqchikel accounts speak of the arrival of "mexicanized" groups coming from Tula around 1200 CE. These groups of Maya-Mexicans married members of the local governing groups, thus giving rise to the future ruling classes of the K'iches, Kaqchikeles and Tz'utujil nations. Archaeological evidence confirms this contact with Mexican populations and traditions and the adoption by local elites of many cultural traits originating in Mexico.

The Annals mention that two lords or kings exercised power before the conquest. Their position was hereditary and they had the titles of Ahpoxahil and Ahpozotzil. Beneath them, there were other nobles of minor importance: the Ahpopcamhay and Ahpop Achi. All of the lords and members of the high nobility were commonly called ajawab, which can be translated as "lord, owner, chief or cacique". The lowest stratum of nobility were known by the term ac'animak, or "nobleman's relative", also translated as "family of a noble" or "principal or authority".

The two lords of lximché lived in the center of the city. They probably occupied, with their Court, the so-called "Palace 1" in Plaza B and "Palace 2" in Plaza C, while other members of the nobility lived in the buildings of Plaza D, which is still uninvestigated.

The death of the kings was accompanied by great changes in the city. Martín Alfonso Tovilla wrote in 1635 about the K'iches that "when a king died, all the streets and palaces were whitewashed inside and out and new histories were painted." It is very possible that the different layers of stucco found in the buildings of the plazas of Iximché correspond to similar practices.

On the other hand, the different superimposed levels of construction of the palaces and temples, as well as the many graves found in their patios, could indicate that at the death of a lord he was cremated or buried in a plaza. Later, his dwelling was destroyed and a new palace or temple was rebuilt for the new king or lord.

Captions:

A diadem made of a smooth gold band, found in grave 27.

A gold necklace composed of 10 small jaguar heads and 36 spherical beads made of the same material, belonging to the same individual

An embossed gold plate with an image of an owl. Coming from the same grave, this ornament was probably sewn to the lord's attire.

Representation of a lord with his clothes and accessories.

The beginning of the Postclassic Mayan religion are found as early as the Preclassic Period when, in all of the early cities in the Maya Zone, elites began to build pyramids to honor their dead, indicating a practice of ancestor worship that lasts beyond the Spanish Conquest. The ancestors of the Mayan kings of the Classical era were seen to be divine and it is very likely that this belief would also continue throughout later periods. The Mayan religion was from its beginnings based on the relation between man and the universe. Gods and supernatural beings had a very important role: both in the creation of the world (of Nature and Man) and in the functioning of the universe (the Sun rising and setting, rains being needed for a good harvest).

The Mayan religion is polytheistic (of several gods): the divinities and hybrid beings represented in classical iconography are numerous, including both human (anthropomorphic) or animal (zoomorphic) forms. Its characteristics and its aspects are multiple, complementary and sometimes opposed and it is difficult to understand the Classical beliefs only through their representations.

The "later" religion is easier to understand, since the Postclassic Maya of the Yucatán have left manuscripts (codices) with representations of gods and details of ceremonies. There are also indigenous and Spanish texts from the moment of first contact.

While the Maya of the Preclassic and Classical times worshiped the natural forces, represented by changing beings, in the Postclassic, the images of the divinities were fixed forming a hierarchical pantheon of gods. This Classic Mayan religion is where we find the worship of the ancestors, solar deities, the underworld, the cardinal points and the center, the rising and the western sun and good harvests. Migrations from the Mexican Highlands also brought with them a cult of warlike deities and ceremonial changes with the introduction of image worship (idolatry) and the remarkable increase in human sacrifice that already existed in the Maya Zone since the Preclassic.

The changes through time of religious beliefs and practices can be explained both by the Mexican influence and by the weakening political power of the ruling class of the different groups and the warlike environment of the time. While during the Classic the leader was worshiped, represented in the stelae and descended from the gods; in the Postclassic, the rituals and sacrifices of the elites were intended for warlike deities.

As far as the mythology of the Highlands of Guatemala is concerned, the most valuable source, although after the Conquest, is undoubtedly the Popol Vuh, the sacred book of the K'iches.

Captions:

Representation of a hybrid zoomorph creatire, from a stone altar of the Lowlands of the Late Classic period. (Photo: R. Sibille).

Postclassic religion: gods and ceremonies represented in the Codex of Madrid, Yucatecan Postclassic manuscript, elaborated as a ritual almanac.

Iximché, a fragmented stone sculpture, perhaps a stone representation of a divinity.

Divine representation in a polychrome censer of Iximché.

These were made up of both common Kaqchikeles and members of conquered groups. The condition of being a vassal was apparently hereditary; nevertheless marriage between vassals and nobles was not unknown. This class of society is little known in archeology. We know from texts that this group, ruled by a law different from that of the nobles, provided different tributes to the ruling elite, allowing it to retain its status. They supplied the elite with food, stones and other building materials as well as raw materials for handicrafts and manufactured objects, as well as making clothes and weapons. The vassals were also the labor force for the construction of the roads and public and religious buildings. They were soldiers in the wars and spectators in the religious ceremonies carried out in the center of the city. They lived outside the fortified center of Iximché, on the slopes of the periphery and in the surrounding fields. This population was, like the K'iches, organized in districts - chinamit - that united several patriarchal groups of submissive vassals, and that they carried the name of the same noble lineage. In the case of an enemy attack, the vassals, as in medieval European times, sought refuge in the fortified center.

The servants and the slaves

All sources from the XVI century agree that slavery was developed in both the Kaqchikel and K'iche nations. R. Carmack defines two types of servile individuals, whom he calls "servants" and "slaves." Servants were also called nimak achi - large people - were probably members of conquered ethnic groups whose whole groups, including their principal leaders, had been taken to the city. They achieved a relatively privileged social position, comparable to that of the vassals. They kept their language, formed their own sections in the neighborhoods, paid taxes and services, and participated in wars. However, they had fewer rights and had to perform more mandatory services. They made up a servant class.

Slaves were prisoners of war. The lords captured in a war were immediately sacrificed, while their vassals entered bondage before being sacrificed. Called munil - slave, captive, prisoner - or winakitz - “collar boy” – they were destined to the serve in the houses of the lords, in which they lived waiting to be sacrificed.

Current historians think that the initial tripartite structure of society was somewhat transformed at the end of the fifteenth century, with the emergence of a "middle class", coming from either the people or from the lesser nobility, and composed of military and enriched merchants and craftsmen. The presence of this intermediate group would perhaps have destabilized the power of kings and nobles, creating friction in society. While the system of nobles, vassals and slaves could work, problems arose with the growing power of these specialized classes, weakening the Kaqchikel state on the eve of the Conquest.

Captions:

Map drawn by Francisco Antonio de Fuentes y Guzmán, showing the separation of the districts of Iximché, published in his "Recordación Florida" at the end of the 17th century .

Possible portrait of a lord, from a detail of a ceramic censer

The ceremonies were carried out both important dates established in the Mayan calendar, and also at special moments, and their development and modalities varied depending on the occasion. The ascension to the throne of a new lord, his death, the repair of a temple, the preparation of the army for war or their victorious return, provided special occasions for protection ceremonies or to thank the deities represented by wooden or stone statues or by figurines. The excavations carried out in the buildings of Plazas A, B and C revealed remains of the different religious practices of the elite of Iximché.

The burning of incense

Many of the Postclassic ceremonies included this practice. The pom (local incense) and other substances, such as latex, were burned in pots of various shapes in the temples in many locations: in front of the temples, at the foot of the pyramids, in processions from one place to another, in the palaces or in the houses. (See the panel on censers located in Plaza A).

The "relics"

The discovery in Temple 3 of a fragmented "plomiza" type vessel, which were no longer produced in the fifteenth century, could indicate that, just like during the Classic Period in the Lowlands, some objects that were identified with ancient properties of the ancestors, were preserved as a relic.

Music

A fragment of a flute carved from human bone and several fragments of ceramic ocarinas, are the musical instruments of lximché that have lasted until our days.

The Sacrifice of Animals

Practiced from the Classic Period to the present day, it had in the Postclassic period the purpose of feeding the gods with the blood of the sacrificed animals. Bishop Landa of Yucatán says that they anointed the "idols" (the statues of the gods) with this blood. The type of animal was chosen according to the recipient of the ritual.

There are no direct vestiges of the slaughter of animals in lximché. However, in front of Temple 2, a stucco block of cylindrical shape, about 40 cm in diameter and about 20 cm thick with a slightly concave top was found, very similar to the Aztec sacrificial stones and which had perhaps the same use.

The question of whether the sacrifices made on the stone were animal or human remains unresolved today.

Captions: Anthropomorphic ocarina found in Plaza C

Polychrome censer with anthropomorphic representation, in which incense was burned.

This practice was common among the Maya since very remote times. It was practiced in caves or in the darkness of the temples. It was a rite of purification as well as a way to “feed the gods”. Self-sacrifice consisted of having the ears, tongue or penis bleed by cutting with a sharp piece of obsidian or a stingray needle. Considered as an individual act of contrition, it could nevertheless be performed in certain collective ceremonies of the Postclassic. It was practiced in lximché as witnessed by detail shown in murals of Temple 2 in which an individual practices self-sacrifice by piercing his tongue.

Human Sacrifice

Present in all of Post Classic Mesoamerica, human sacrifice was probably less common than the sacrifice of animals. Although the goal of feeding and pleasing the gods was the same, this practice was reserved for special occasions. It may have been linked in most cases to the practice of the Ball Game.

In Iximché, the victims of the sacrifice were beheaded, after having their hearts removed. Two deposits of skulls associated with obsidian knives were found in the vicinity of two small structures located south of Temples 2 and 4 in Squares A and C, between the Temples and the Ball Court. The skulls (a total of 25 individuals) retained the first cervical vertebrae but included signs of decapitation. They were both men and women, ranging in age from 15 to 25 years. The representation of the two sexes clearly indicates that they were not ball players but probably captives of war.

Guillemin identified the small structure located in front of Pyramid 2 in the vicinity of which the skulls were found, as a possible Tzompantli: a place where the heads of the sacrificed were exhibited, mounted on wooden stakes, and whose walls are, as in an example at Chichen Itza, decorated with long bones and human skulls.

Grave 27-A, probably of one of the lords of Iximché, shows another type of human sacrifice: that of the companions of the lord on his journey to the Underworld. There, while the lord was buried in a sitting position with all his accessories made of gold, three individuals were sacrificed for the occasion and placed in a flexed position in the pit, accompany him in his last dwelling.

Captions:

Self-sacrifice of the tongue from the murals of Temple 2.

Scene of human sacrifice by extraction of the heart, from the Nuttall Codex, Oaxaca, Mexico.

Skull of a beheaded individual found in one of the buildings of Plaza A.

Obsidian knife found in the deposit of skulls from Plaza A, possibly used during sacrifices.

Erected by Instituto de Antropología e Historia (IDAEH) de Guatemala.

Topics. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: Anthropology & Archaeology • Architecture • Colonial Era • Native Americans. A significant historical year for this entry is 1200.

Location. 14° 44.098′ N, 90° 59.759′ W. Marker is in Tecpán Guatemala, Chimaltenango. The marker is some meters west of Plaza A at the Archaeological Park of Iximche. The park is south of the city of Tecpán Guatemala on a road known locally as the "Road to Iximche". Touch for map. Marker is in this post office area: Tecpán Guatemala, Chimaltenango 04006, Guatemala. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. Sotz'il Palace (within shouting distance of this marker); Plaza A of Iximche (about 90 meters away, measured in a direct line); Mayan Civilization in the Post Classic Period (about 120 meters away); Mesoamerica and the Mayan Civilization (about 120 meters away); Temple 5 at Iximche (about 120 meters away); Xajil Palace (about 120 meters away); Southwest Area (about 120 meters away); Artisans and Exchanges at Iximché (about 180 meters away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Tecpán Guatemala.

Credits. This page was last revised on March 2, 2018. It was originally submitted on October 20, 2017, by J. Makali Bruton of Accra, Ghana. This page has been viewed 324 times since then and 13 times this year. Photos: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. submitted on October 20, 2017, by J. Makali Bruton of Accra, Ghana.