From Enslaved to Community Activist / The Original Power Couple

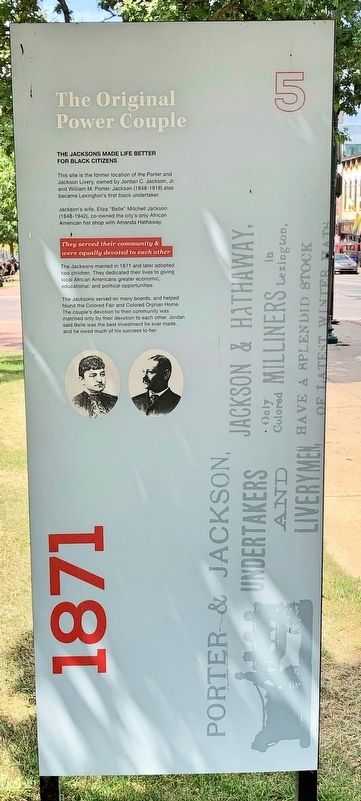

1871

— Downtown African-American Heritage Trail —

Education Gave the Jacksons a Step Up

Jordan C. Jackson, Jr. was born enslaved in Lexington. Denied an education, he taught himself to read and write, eventually becoming a successful businessman and newspaper editor. He co-owned a livery at this site.

Jackson twice served as a Republican National Convention delegate. He protested a law that segregated train passengers by race, chaired the committee establishing Douglass Park, and pushed for an African American college—now Kentucky State University.

Teaching in the face of opposition

His wife, Eliza "Belle" Mitchell Jackson, was born in Perryville, Kentucky, to former slaves who had purchased their freedom before her birth.

Belle devoted her life to education. As a teenager, she became the first black teacher at Camp Nelson. Teachers from the American Missionary Association refused to eat and sleep in the same area as "a woman of color." They petitioned for her removal, but Belle made the decision to leave.

After Camp Nelson, Mrs. Jackson was invited to teach at the Missionary Free School of Color in Lexington. She would go on to teach in Frankfort, Louisville, Nicholasville, and Richmond.

The Jackson Made Life Better for Black Citizens

This site is the former location of the Porter and Jackson Livery, owned by Jordan C. Jackson, Jr. and William M. Porter. Jackson (1848-1918) also became Lexington's first black undertaker.

Jackson's wife, Eliza "Belle" Mitchell Jackson (1848-1942), co-owned the city's only African American hat shop with Amanda Hathaway.

They served their community & were equally devoted to each other

The Jacksons married in 1871 and later adopted two children. They dedicated their lives to giving local African Americans greater economic, educational, and political opportunities.

The Jacksons served on many boards, and helped found the Colored Fair and Colored Orphan Home. The couple's devotion to their community was matched only by their devotion to each other. Jordan said Belle was the best investment he ever made, and he owed much of his success to her.

Erected 2018 by Together Lexington. (Marker Number 5.)

Topics and series. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: African Americans • Churches & Religion • Civil Rights • Education • Railroads & Streetcars • Women. In addition, it is included in the Historically Black Colleges and Universities series list. A significant historical year for this entry is 1871.

Location.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. Lexington's Long History with Slavery / Driven by Money (within shouting distance of this marker); Skuller's Clock (about 400 feet away, measured in a direct line); Black Lexingtonians Believed Strongly in Education 1865 (about 400 feet away); Rotary Club of Lexington / Phoenix Hotel (about 400 feet away); Strength in Numbers / Forcing a Change (about 400 feet away); Phoenix Park (about 400 feet away); Lewis and Clark in Kentucky (about 500 feet away); Slavery in Fayette Co. / Cheapside Slave Auction Block (about 500 feet away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Lexington.

Regarding From Enslaved to Community Activist / The Original Power Couple.

Jim Crow (1865-1950s)

Legal and financial networks during this time refused to serve or protect African-Americans. They were spatially segregated in housing options, transportation systems, and public spaces, and deprived of quality education, healthcare, and employment.

Those who challenged these systems were met with violence, but threats did not prevent resistance. Many did not accept these practices and used activities in their daily lives to shape their own identities. Lexington was home to a range of vocal activists, philanthropists, and successful entrepreneurs that did not let oppression define them.

Also see . . . Downtown African-American Heritage Trail website about marker. (Submitted on July 29, 2019, by Mark Hilton of Montgomery, Alabama.)

Credits. This page was last revised on February 12, 2023. It was originally submitted on July 29, 2019, by Mark Hilton of Montgomery, Alabama. This page has been viewed 304 times since then and 44 times this year. Photos: 1, 2, 3, 4. submitted on July 29, 2019, by Mark Hilton of Montgomery, Alabama.