Troy in Greenwood County, South Carolina — The American South (South Atlantic)

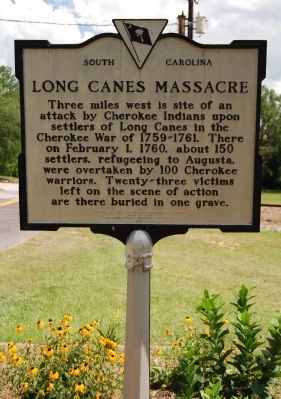

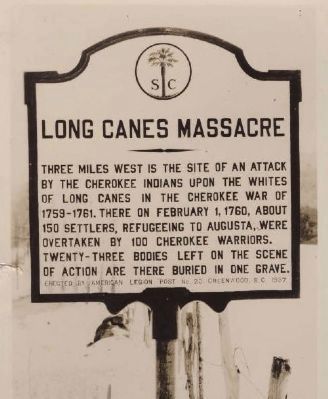

Long Canes Massacre

Erected 1976 by Abbeville District Historical Association, Town of Troy, McCormick County Historical Commission. (Marker Number 24-1.)

Topics. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: Cemeteries & Burial Sites • Colonial Era • Military • Native Americans • Notable Events • Settlements & Settlers. A significant historical month for this entry is February 1864.

Location. 33° 59.261′ N, 82° 17.864′ W. Marker is in Troy, South Carolina, in Greenwood County. Marker is on Main Street West near Twigg Street (South Carolina Highway 10). Touch for map. Marker is in this post office area: Troy SC 29848, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within 6 miles of this marker, measured as the crow flies. Long Cane Associated Reformed Presbyterian Church (here, next to this marker); a different marker also named Long Canes Massacre (approx. 2.4 miles away); Badwell / Badwell Cemetery (approx. 4.4 miles away); Bradley CCC Camp F-7 (approx. 5.1 miles away); Dorn Mill (approx. 5.2 miles away); Dorn Mill Complex (approx. 5.2 miles away); Dornís Mill / Dorn Gold Mine (approx. 5.2 miles away); McCormick County / MACK (approx. 5.2 miles away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Troy.

More about this marker. The current marker replaced one that was weathered and hard to read. It is recorded in the SC Highway Historical Marker Guide (2nd ed. 1996) that this may be the oldest marker in South Carolina.

Also see . . .

1. The Long Cane Massacre, as described in The Scotch-Irish, & their 1st Settlements on the Tyger River. The following excerpt was taken from The Scotch-Irish, and their First Settlements on the Tyger River, and Other Neighboring Precincts in South Carolina, a Centennial Discourse, delivered at Nazareth Church, Spartanburg District, S.C., September 14, 1861, by George Howe, D.D.; reprinted 1981 by A Press, Inc., Greenville, South Carolina. (Submitted on July 22, 2008, by Brian Scott of Anderson, South Carolina.)

2. Long Canes Massacre of 1760. Includes photos taken in 2007 of the site and surrounding area. (Submitted on September 9, 2008, by Brian Scott of Anderson, South Carolina.)

Additional commentary.

1. Cherokees killed 56 settlers at Long Cane Massacre

February 1, 1760, was a cold, winter day in the Calhoun settlement at Long Canes. During the morning the settlers received the alarm of an impending attack planned by Indian warriors from the Lower Towns and the Middle Towns of the Cherokee Nation. Risking her life, Cateechee, a Cherokee maiden, rode some 70 miles on horseback from her Keowee home in the Lower Towns to warn settlers. The daring dash by Cateechee probably saved the Long Canes settlement from total annihilation.

The settlers hastily began preparations to flee some 60 miles south to Toblerís Fort at Beech Island in New Windsor Township, just across the Savannah River from Augusta.

John Tobler, a Swiss settler, had set up a thriving plantation there that included an ironworks, a clock making business, and a printing shop that published The South Carolina Almanack. He, like William Calhoun, was engaged in Indian trade. It is likely that the Calhouns and Tobler were already well acquainted. Tolbert's extensive compound was enclosed inside a sturdy palisade fort.

The decision to flee would prove to be a fatal one, traveling in loaded wagons whereas the attackers were on horseback. With a few hours of work building a stockade

the men could have probably successfully defended their families. But, of course, the settlers did not know the imminence of the impending attack.

Within hours of the warning, a first group of over 100 people left the Long Canes and would reach Toblerís Fort unmolested.

Shortly thereafter the rest of the settlers moved out in a wagon train of about 150 people. Travel was hampered due to the ground being soggy wet from recent rainy weather. After traveling a few miles they reached Long Cane Creek. They experienced great difficulty in crossing the creek and climbing the hill on the east side. By that time it was late and the decision was made to make camp for the night.

Meanwhile, a Cherokee war party of about 100 Indian braves, reportedly led by Chief Big Sawny and Chief Sunaratehee, arrived at the Long Canes settlement and found it abandoned. They pursued the trail of the settlers for a while and decided to cease pursuit. At the moment they were about to turn around, they faintly heard shouts of the fleeing settlers as they probably were making the creek crossing. The war party quickly resumed pursuit, crossed the creek at another site and went into hiding.

When at the settlersí most defenseless moment, the Indians attacked. The campsite was at once a scene of total pandemonium. In the wild confusion only a few of the 55 to 60 fighting men could lay hand on their guns. Women and children scrambled for any available cover and became separated. Casualties among the settlers mounted very quickly. The men were able to hold off the attacking Indians for no more than a half-hour. Realizing the futility of further resistance the surviving settlers, aided by then night, assembled as best they could and fled on horses, leaving behind the wagons containing all their earthly possessions.

The next day survivors reached the safety of Toblerís Fort. Immediately Patrick Calhoun sent a messenger to Charles Town to inform the governor of the massacre.

In the short half-hour the Long Canes settlers suffered 56 killed and a number taken captive. James Calhoun, commander of the settlement and eldest of the Calhoun brothers, was killed. Five of those killed were members of the Norris family: Robert Norrisí mother, wife, two sons and one daughter. Margaret Clarkís husband was killed, and her six-year-old daughter captured.

The Cherokee raiding party sustained 21 killed and a number wounded. Among the killed was Chief Sunaratehee.

At the beginning of the battle William Calhoun saw his daughter Catherine, 7, killed, and his daughters Anne, 4, and Mary, 2, taken captive. Panic-stricken, he cut a horse loose from a wagon, and loaded his pregnant wife, Agnes Long Calhoun, and only remaining child, Joseph, 9. He told them to head south toward Toblerís Fort and to try and overtake the group that had left Long Canes first. Somehow she escaped and rode hard until dark but did not catch up with the first group. She did come upon a deserted cabin and found some food. Now, lost from both groups and not knowing their fate, at dawnís first light, Agnes Calhoun mounted the horse with Joseph and headed south. The two unlikely refugees made it to Toblerís Fort in good condition. A few days later on February 18th a son Patrick was born to William and Agnes Calhoun.

Two or three days after the massacre Patrick Calhoun, with a militia troupe, returned to the battle site. At one location they found the bodies of 23 victims, including that of Catherine Calhoun, the 76-year-old matriarch of the Calhoun family. The victims were women and children who had all hovered around a large tree in a vain effort to escape death. They were buried in a mass grave where they were killed. The other victims were buried at another nearby location in a second mass grave near to where they fell.

Children were found wandering in the woods. One man found nine children, some of whom had been cut with tomahawks and left for dead. Others were found on the bloody ground scalped, yet still living.

Rebecca Calhoun, 15, daughter of Ezekiel and Jean Ewing Calhoun, was found hiding in the woods. She revealed that she has escaped by crouching unnoticed in a cane brake. Five years later on March 19, 1765, Rebecca became the wife of Andrew Pickens, who, during the American Revolution became an illustrious patriot general. She was the mother and the grandmother of governors of South Carolina – Andrew Pickens, 1816-1818, and Francis W. Pickens, 1860-1862.

The militia then left the battle site and headed back to investigate the status of the settlersí homes that they found damaged and pillaged by the Indians. On the road some distance from the battle site the body of another victim was found. The little blue-eyed girl had suffered a terrific tomahawk blow to the head. Apparently, she, having regained consciousness, had attempted to return to her home in the Calhoun settlement. Her body was wrapped in a blanket and buried beside a large poplar tree with a field stone to mark the grave. As late as the 1920s, the gravesite could be identified because farmers had left a clump of trees in their original state to cloak the location.

The Long Canes settlers remained for several weeks in the security of John Toblerís fortified compound at Beech Island. The compound was well stocked with provisions. Three weeks after his people had nearly been wiped out, Patrick Calhoun was in Charles Town pleading for military aid to protect the Long Canes settlement. The South Carolina Gazette reported, “Mr. Patrick Calhoun, one of the unfortunate Settlers at Long-Canes, who were attacked by the Cherokees on the 1st Instant, as they were removing their wives, children and best effects, to safety, is just come to town, and informs us that the whole of those settlers might be about 250 souls, 55 or 60 of them fighting men; that their loss in that affair amounted to about 50 persons, chiefly women and children, with 13 loaded wagons and carts; that he had since been at the place where the action happened, in order to bury the dead; and that he believes all the fighting men would return to and fortify the Long-Canes Settlement, were part of the Rangers so stationed as to give them some Assistance and Protection.”

When the situation was adequately improved, the Long Canes refugees left Toblerís Fort at Beech Island, and established a temporary home at the Waxhaws settlement of Scots-Irish near present-day Lancaster. Many of the Long Canes settlers had stopped over at the Waxhaws on their way to locate at Long Canes and some had relatives there.

Two days after the massacre at Long Canes, on February 3rd the fort at nearby Ninety Six was attacked by a force of over 200 Cherokee Indians led by Chief Young Warrior. All the surrounding buildings were burned but the fortís defenders withheld the attack. The fortís commander wrote to Governor William Henry Lyttleton, “We fattened our dogs with their (the Indians) carcasses.” In reply the governor directed the commander to, “display their scalps neatly ornamented to the tops of our (fortís) bastions!”

A Cherokee war party attacked the Stevens Creek settlement, which was located about ten miles southeast of present-day Modoc, killing twenty of the settlers. 170 survivors, under the leadership of George Bussey, fled for safety to Fort Moore, which was located a few miles from Tobler's Fort.

The Cherokee raiding parties across the upstate varied in number from a dozen or so to over a hundred. Only the stockade forts, which within a week of the Long Cane massacre, dotted the South Carolina frontier, prevented wholesale carnage in the upstate. These hastily constructed forts were in time improved and strengthened so as to provide a safe haven for settlers. (Source: The Making of McCormick County by Bobby F. Edmonds (1999), pgs 17-21.)

— Submitted September 9, 2008, by Brian Scott of Anderson, South Carolina.

2. Anne Calhoun Returned

After the end of the Cherokee War, there was a prisoner release by the Cherokee Indians, brought about through the negotiations of Andrew Pickens. Upon the appointed day, William Calhoun attended the proceedings with the obscure hope that he might find his Anne and Mary, who had been carried away by the Indians more than a year earlier. Anne had been 4 and Mary 2. Watching with eagerness as each prisoner was brought forward, he at last saw Anne, and instantly identified her by a burn scar. She had the appearance of an Indian maiden and spoke not a word of English.

But the day also brought sad news when it was revealed that Mary Calhoun was, on the day of the massacre, scalped and her body thrown into Long Cane Creek.

Anne Calhoun, then nine years old, learned to speak English again but would never learn to read or write. She would throughout her life wear moccasins made of the bark of certain trees. A Calhoun family descendant wrote that Anne retained the character of an Indian woman and “was almost hated by her family.” Anne later in life would sadly assert that she was punished by the Indians to make her cultivate their ways and, in turn, admonished by her family to revert to theirs.

Anne married Isaac Matthews, a nearby farmer, in 1784, when she was 29. They raised six children, Joseph, Mary, Nancy, Ann, John, and Lewis. The descendant wrote, “she did not fancy the harsh name of Isaac so she called her lover Zacky. Her great strength of endurance and energy lent a charm to the young farmer as a helpmate.”

Anne often longed for her wild Indian life and would steal away sometimes at early dawn and spend the whole day in the woods. Into the dense forest she would go, she said to whisper to the spirits that she could not see, but could hear them gliding away from tree to tree. Once Zacky followed her and found her eating lizards and frogs. She had imbibed the old way of eating. She never revealed emotions or got excited.

Her children grew up and left her. Then in 1801 Zacky died. Afterward she led a lonely desolate life. Her brother, Joseph Calhoun, owned Calhoun Mill. During his life Anne was allowed to get anything she wished from the mill. Every week she could be seen on the old white mare wending her way with two sacks, for meal and flour. She enjoyed telling children stories of her life among the Cherokees.

On her last Christmas, a relative made Anne a muslin cap with two wide frills on it and a kerchief to match. The old lady was much pleased with the present and thanked the giver saying, “Itís too nice to wear now. I will save it until I die. You must put it on me. Then when Zacky will meet me, he will say, Anne, how beautiful you look!” (Source: The Making of McCormick County by Bobby Edmunds (1999), pgs 28-29.)

— Submitted September 9, 2008, by Brian Scott of Anderson, South Carolina.

Credits. This page was last revised on June 16, 2016. It was originally submitted on July 22, 2008, by Brian Scott of Anderson, South Carolina. This page has been viewed 4,975 times since then and 116 times this year. Photos: 1, 2. submitted on July 22, 2008, by Brian Scott of Anderson, South Carolina. 3. submitted on November 27, 2009, by Brian Scott of Anderson, South Carolina. • Christopher Busta-Peck was the editor who published this page.