Luray in Page County, Virginia — The American South (Mid-Atlantic)

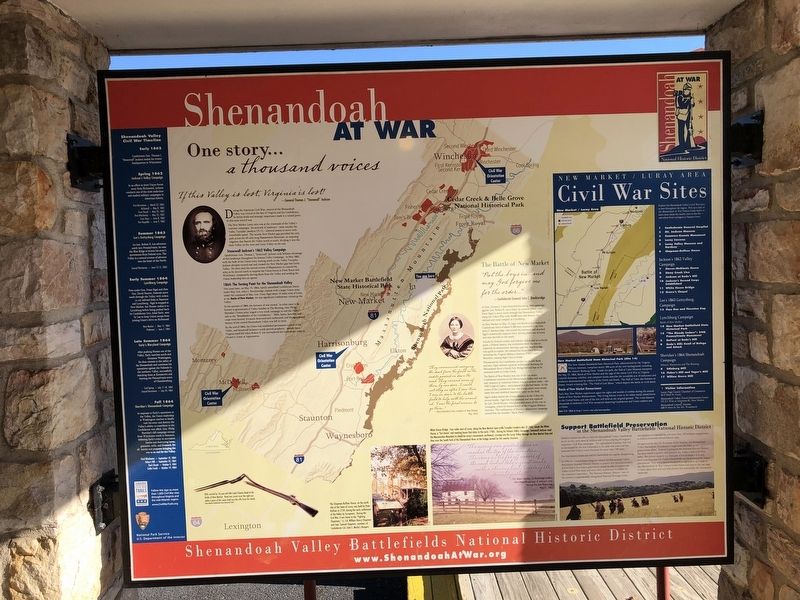

Shenandoah At War

One story… a thousand voices

If this Valley is lost, Virginia is lost!

— General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson

During the American Civil War, control of the Shenandoah Valley was critical to the fate of Virginia and the Confederacy. Its fertile fields and strategic importance made it a valued pawn in this most uncivil war.

The New Market-Luray area was at the crossroads of the Valley's wartime campaigns. Its network of roadways — most notably the Valley Turnpike (modern US 11) — allowed armies to move with remarkable speed. The nearby New Market gap provided the only path across the 45-mile Massanutten Mountain, an imposing ridgeline that bisects the Valley north to south, dividing it into the main Valley on the west and Luray Valley on the east.

Stonewall Jackson's 1862 Valley Campaign

Confederate Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson took brilliant advantage of this landscape throughout his famous Valley Campaign. In May 1862, with the bulk of the Union army waiting north on the Valley Turnpike, Jackson abruptly turned east and crossed the New Market gap into Luray Valley. He then used the natural screen of Massanutten to conceal his army as he moved north to surprise the Union forces at Front Royal and Winchester, temporarily driving them from the Valley and sending the Union leadership into an uproar.

1864: The Turning Point for the Shenandoah Valley

Two years later, on May 15, 1864, hastily assembled Confederate forces under Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge clashed with a larger Union army under the command of Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel about 15 miles west of Luray at the Battle of New Market, the last significant Confederate victory in the Valley.

In the autumn of 1864, the fortunes of war turned. In what came to be known to generations of Valley families as The Burning, Gen. Philip Sheridan's Union army waged a two-week campaign to end the Valley's role as the "Breadbasket of the Confederacy." Mills, barns, factories, and crops were burned, livestock destroyed and confiscated, and the agricultural bounty of the central Shenandoah Valley was left in ruins.

By the end of 1864, the Union had established permanent control of the Valley, and Stonewall Jackson's words proved prophetic: months later, Virginia itself fell when Robert E. Lee surrendered his Confederate army to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox.

The Battle of New Market

"Put the boys in…and may God forgive me for the order…"

— Confederate General John C. Breckinridge

As Gen. Ulysses S. Grant launched his spring 1864 campaign against Gen. Robert E. Lee's army, he ordered Union en. Franz Sigel to move south through the Shenandoah Valley along the Valley Pike with 10,000 men and destroy the railroad and canal complex at Lynchburg.

At New Market on May 15, Sigel was blocked by a makeshift Confederate force of about 5,300 men commanded by Gen. John C. Breckinridge, who seized the initiative and attacked Sigel's numerically superior force, driving them out of town and onto the hills to the north.

Attacks by Federal cavalry and infantry failed, and at a crucial point, a Federal battery was withdrawn from the line to replenish its ammunition, leaving a gap that Breckinridge was quick to exploit. He ordered his entire force forward, including the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) Cadet Battalion, causing Sigel's line to break.

The Battle of New Market was one of the last major Confederate victories in the Shenandoah Valley and was the only instance in American history where a student body—the VMI Corps of Cadets—participated in a pitched battle. At the center of the Confederate line, the young cadets were steady under fire and exhibited impressive valor on the field.

Sigel's defeat halted the Union offensive in the Valley for several weeks. Sigel lost his command and was replaced by Gen. David Hunter, who proceeded south all the way to Lexington, where he burned much of the Virginia Military Institute. The ruthlessness of Hunter's destructive campaign earned him the moniker "Black Dave".

"They commenced carrying the dead from the field as the cadets passed on down the road. They carried some of them by our door… I could not stay in after I saw this, I ran on down to the battle field to help with the wounded. I was the first woman to go there…"

— Eliza Clinedinst Crim, resident of new Market, May 1864

Shenandoah Valley Civil War Timeline

Early 1862

Confederate Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson makes his winter headquarters in Winchester.

Spring 1862

Jackson's Valley Campaign

In an effort to draw Union forces away from Richmond, Jackson conducts one of the most audacious and studied military campaigns in American history.

First Kernstown — March 23, 1862

McDowell — May 8, 1862

Front Royal — May 23, 1862

First Winchester — May 25, 1862

Cross Keys — June 8, 1862

Port Republic — June 9, 1862

Summer 1863

Lee's Gettysburg Campaign

As Gen. Robert E. Lee advances north into Pennsylvania, he uses the Blue Ridge to screen his army's movements from Federal eyes. The Valley is a natural avenue of advance into the heart of the North.

Second Winchester — June 13-15, 1863

Early Summer 1864

Lynchburg Campaign

First under Gen. Franz Sigel and then Gen. David Hunter, Federals move south through the Valley with orders to cut railroad links at Staunton and Lynchburg. Sigel is stopped at New Market, but Hunter makes it to Lynchburg before being pushed back by Confederate Gen. Jubal Early, sent by Lee to keep Union troops from joining Grant's drive on Richmond.

New Market — May 15, 1864

Piedmont — June 5, 1864

Late Summer 1864

Early's Maryland Campaign

After pushing Hunter out of the Valley, Early marches north and threatens Washington. He then retreats to the safety of the Shenandoah and continues his operations against the Federals in the northern Valley, successfully attacking them at Kernstown and burning the Pennsylvania town of Chambersburg.

Cool Spring — July 17-18, 1864

Second Kernstown — July 24, 1864

Fall 1864

Sheridan's Shenandoah Campaign

In response to Early's operations in the Valley, the Union leadership in Washington resolves to finally rush and his army destroy the Valley's ability to contribute to the Confederate war effort. Gen. Philip Sheridan's fall campaign sweeps from Winchester south to Staunton, defeating Early's army in successive battles and destroying barns, granaries, mills, and livestock, for all intents and purposes bringing the war to an end for the Valley.

Third Winchester — September 19, 1864

Fisher's Hill — September 22, 1864

Tom's Brook — October 9, 1864

Cedar Creek — October 19, 1864

[Sidebars and captions:]

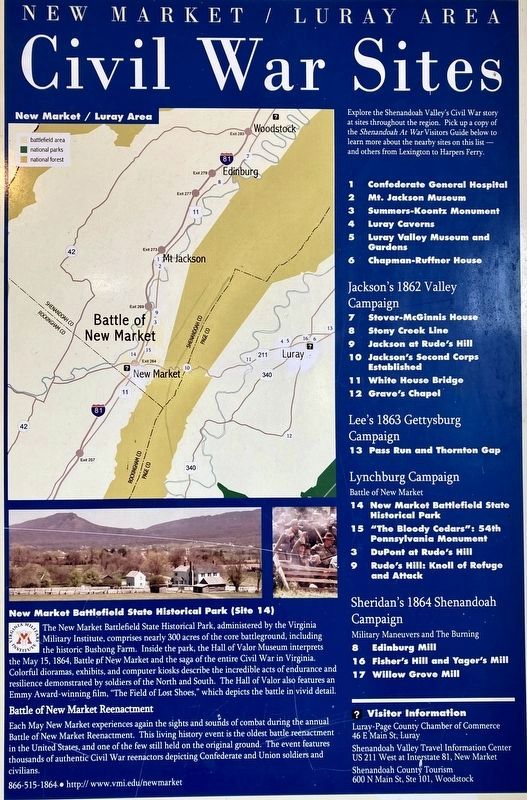

New Market Battlefield State Historical Park (Site 14)

The New Market Battlefield State Park, administered by the Virginia Military Institute, comprises nearly 300 acres of the core battleground, including the historic Bushong Farm. Inside the park, the Hall of Valor Museum interprets the May 15, 1864, Battle of New Market and the saga of the entire Civil War in Virginia. Colorful dioramas, exhibits and computer kiosks describe the incredible acts of endurance and resilience demonstrated by soldiers of the North and South. The Hall of Valor also features Emmy Award-winning film, "The Field of Lost Shoes," which depicts the battle in vivid detail.

Battle of New Market Reenactment

Each May New Market experiences again the sights and sounds of combat during the annual Battle of New Market Reenactment. This living history event is the oldest battle reenactment in the United States, and one of the few still held on the original ground. The event features thousands of authentic Civil War reenactors depicting Confederate and Union soldiers and civilians.

866-515-1864 • http://www.vmi.edu/newmarket

The Chapman-Ruffnor House, on the north side of the Town of Luray, was built by Peter Ruffner in 1739, during the early settlement of the Valley by Europeans. During the Civil War, it was home to the "Fighting Chapmans," Lt. Col. William Henry Chapman and Capt. Samuel Chapman, members of Confederate Col. John S. Mosby's Rangers.

White House Bridge: Four miles west of Luray, along the New Market Sperryville Turnpike (modern-day US 340), stands the White House, a "fort home" and meeting house that dates to the early 1700s. During his famous Valley Campaign, Stonewall Jackson used the Massanutten Mountain to shield his army's movements northward, crossing into the Luray Valley through the New Market Gap and then over the South Fork of the Shenandoah River at the bridge named for his nearby structure.

"The rising sun greeted us as we reached the tip of the mountain… The army in the far off curves of the road looked like a giant snake with a shining back, twisting its sinuous path…"

— Pvt. Robert Barton, 1st Rockbridge Artillery describing the passage of Jackson's army through the New Market Gap, May 21, 1862

Support Battlefield Preservation in the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District

Modern visitors are able to view the Shenandoah Valley's battlefields much as they were seen by soldiers and civilians during the region's important Civil War campaigns. The agricultural economy that was so devastated by the war rebounded in the post-war years and has sustained the Valley's rural character for more than 140 years.

But this historic landscape and the battlefields are rapidly disappearing.

In 1996 the United States Congress created the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District to protect this national resource and to ensure that future generations would be able to explore the Valley's Civil War story and more fully understand its impact on the American experience. The National Historic District—one of the nation's congressionally-designated National Heritage Areas—encompasses ten battlefields and more than 325 military engagements as well as numerous related historic sites.

As approved by the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation is responsible for leading the preservation effort. Federal Funding for the National Historic District has done much to protect and promote the Valley's rich Civil War story. But private support is a vital part of the formula—it is only with your help that the Valley's battlefields can be protected for future generations. Visit www.ShenandoahAtWar.org or pick up a copy of the Shenandoah At War Visitors Guide below and turn to the last page to learn about how you can help protect this remarkable but threatened landscape.

Erected by Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation; Virginia Civil War Trails; National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.

Topics and series. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: Colonial Era • Natural Features • Settlements & Settlers • War, US Civil. In addition, it is included in the Former U.S. Presidents: #18 Ulysses S. Grant series list. A significant historical month for this entry is May 1862.

Location. 38° 39.896′ N, 78° 29.01′ W. Marker is in Luray, Virginia, in Page County. Marker is on Cave Hill Road, 0.2 miles west of Lee Highway (U.S. 211/340), on the left when traveling west. Touch for map. Marker is at or near this postal address: 970 Lee Highway, Luray VA 22835, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. Luray (here, next to this marker); Car & Carriage Caravan Museum (within shouting distance of this marker); The Beautiful Caverns of Luray (about 300 feet away, measured in a direct line); Luray Caverns (about 300 feet away); The Luray Valley Museum (about 400 feet away); The World's First Bluegrass Festival (about 400 feet away); Heartpine Cafe (about 400 feet away); Willow Grove Mill In Olden Days (about 500 feet away). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Luray.

Credits. This page was last revised on August 31, 2023. It was originally submitted on November 1, 2020, by Devry Becker Jones of Washington, District of Columbia. This page has been viewed 260 times since then and 35 times this year. Photos: 1. submitted on November 1, 2020, by Devry Becker Jones of Washington, District of Columbia. 2. submitted on August 15, 2023, by Bradley Owen of Morgantown, West Virginia. 3. submitted on August 21, 2023, by Linda Walcroft of Woodstock, Virginia.